Redistricting—A Political Puzzle

Redistricting is a political puzzle. Fortunately, this time around we can do our own citizen puzzle-solving.

Jim Moore is a longtime observer of Oregon and west coast politics, in addition to a political analyst for various media outlets, and professor at Pacific University.

It is finally time for states to draw their new political districts. Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution mandates an ‘enumeration’ every ten years to “apportion…[representatives] among the several States….” Whether the district lines are drawn by a legislature, a single elected official, or a commission of some kind, this decennial process is profoundly political.

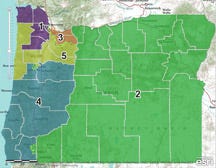

On paper, redistricting seems fairly simple (and non-political). The first round of 2020 Census data from the U.S Census Bureau gave us the round numbers from which to create our new district boundaries. (To see all this, there is a great Oregon Redistricting page on the Oregon State Legislature site.) Simply taking the official 2020 population of a bit more than 4.2 million yields six congressional districts of a bit more than 706,000. Looking at state legislative seats, there thirty senate districts averaging about 141,000, and sixty house districts averaging about 70,500. The math is pretty easy at this point—each congressional district should have five Oregon senate districts and ten Oregon house districts within it.

Beyond the data, things get more complicated (and political) based on laws that govern proper redistricting. For example, the 14th Amendment forbids splitting up racial groups. But subsequent U.S. Supreme Court decisions make it legal to create ‘minority-majority’ districts so that members of minority groups can be elected to legislative bodies. These issues could easily arise as Oregon stakeholders look at the quickly growing Latino population as well as our Black population.

The high electoral stakes tied to district lines also add a political element to redistricting. Due to U.S. Supreme Court rulings in the 1960s, the Oregon legislative seats each have only one officeholder (upholding the one-person, one-vote rule). Before the 1971 redistricting, there were several districts around the state that had multiple members. Under this system, there were some representatives who could win with 3400 out of 6200 votes, and others who won with 27,000 out of 47,500. This was clearly not one-person, one-vote representation.

Oregon adds some rules of its own at this point, further adding to the political nature of redistricting.

The Oregon system requires that each Oregon senate district contain within it two complete house seats. To complicate it even more, Oregon law requires district lines to “utilize existing geographic or political boundaries, not divide communities of common interest, and be connected by transportation links.”

So, what do we have at this point? Again, on paper, it seems like an easy exercise of dividing the state up into a Russian doll of electoral districts. First, decide where to place those six congressional districts. Then, divide those districts up into state Senate seats and finish off with House districts. Finally, apply some nipping and tucking to get those “geographical or political boundaries” and protect “communities of common interest,” and there you are.

Of course, it’s also important to consider population growth trends. Population growth has centered on the Willamette Valley, Deschutes County, and Medford, so some familiar district boundaries would geographically grow (so they contained more population), some would geographically shrink (because their populations increased over the past decade).

That “simple” process is complicated by our political reality, which adds other layers of complexity to be factored in. This political process will look at party registration and try to make the districts reflect local and statewide distributions of political parties. This is usually where gerrymandering enters the equation. State law forbids this, but it happens.

As of this writing, 35% of Oregon registered voters are Democrats, 25% are Republicans, 33% are nonaffiliated, and 7% are registered with minor parties. Should there be nonaffiliated districts (in fifteen counties, where unaffiliated voters are the largest group)? But there aren’t unaffiliated candidates at this point. If we ignore everybody except the Republicans and Democrats, we get 58% Democrats and 42% Republicans. This is actually in the general range of our current party representation in the Oregon Legislature (Senate—60% Ds, 40% Rs; House—62% D, 38% Rs).

There is also the puzzle about where the “Democratic” or “Republican” parts of the state are. Republicans primarily live in the population centers, not east of the Cascades. About half of registered Republicans live in Clackamas, Washington, Marion, Multnomah, and Lane counties. Marion is the only one of these counties with parity between the numbers of Rs and Ds; the rest have heavy Democratic registration advantages.

So, if that simple dividing practice were to settle on these five counties, Republicans would be shut out of representation for the most part.

Redistricting is a political puzzle. Fortunately, this time around we can do our own citizen puzzle-solving. The Oregon Redistricting page also has links to the actual software that will be used to create the new districts. As the Census data arrives within the next few weeks, we can keep a close watch on what our legislators propose. We can even figure out our own solutions and make sure legislators hear from us. It is a once-in-a-decade opportunity. Puzzle solvers should love this.