Cyreena Boston Ashby: Fires are a reminder of the disparate impacts of disasters

While we are rightly focused on the wildfires, flooding is more common in Oregon than people likely realize, and it is important to talk about how to meet this inevitable crisis now.

Disasters disparately impact Oregonians.

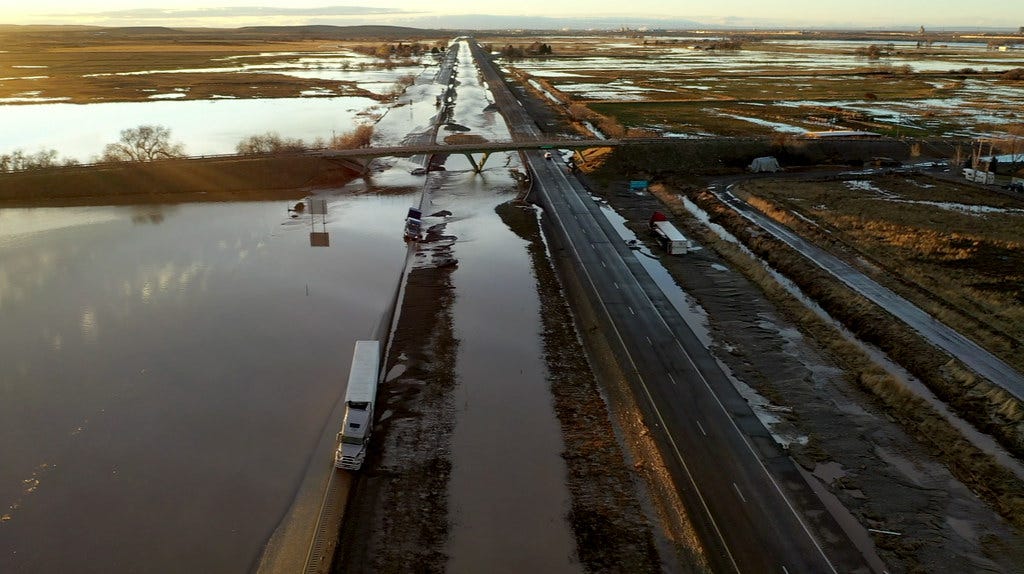

"Overhead view of flooding at Echo Meadows Road" by OregonDOT is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Weeks ago, Hurricane Laura threatened the Gulf Coast with what experts warned as an “unsurvivable” storm surge; they also warned of great flooding. What experts didn’t discuss, but what’s important to consider, is how extreme weather events and floods affect Oregonians. Our Eden-like state had long lulled us into a false sense of safety – surely extreme weather would stay away from our communities. Then came Oregon‘s wildfires. Recently, The Oregonian reported 8 known wildfire fatalities and the destruction of 1,616 homes. As our thoughts are with firefighters and fire impacted communities, it seems very necessary that we examine how fires and floods are interconnected as well as a present and future threat to Oregonians:

Like flooding, research has shown that communities of color—specifically, Census tracts that are majority Black, Hispanic, or Native American—are more vulnerable to wildfire compared to other Census tracts.

Wildfire increases flood risk even for areas that are not traditionally flood prone. Large-scale wildfires dramatically alter the terrain and ground conditions. Normally, vegetation absorbs rainfall, reducing runoff. However, wildfires leave the ground charred, barren, and unable to absorb water. These factors cumulatively create conditions ripe for flash flooding and mudflows. Flood risk remains significantly higher until vegetation is restored—up to 5 years after a wildfire.

Our climate change crisis is fueling deadlier wildfires, hurricanes and flood events. Today, hurricanes are bringing catastrophic flooding to the Gulf Coast; scientists are literally running out of names for the seemingly never-ending production of storms in the Atlantic.

Some of these storms won’t touch Oregonians, but the underlying climate chaos will inevitable reach us – as evidenced by our current fires.

While we are rightly focused on the wildfires, flooding is more common in Oregon than people likely realize, and it is important to talk about how to meet this inevitable crisis and mitigate against damage from extreme weather events. These conversations must be proactive, rather than in response facing life-threatening and heartbreaking decisions.

Floods are the costliest natural hazard in the nation. From 2000 to 2017, flood-related disasters in the U.S. accounted for more than $750 billion in losses—of course, the human toll is nearly impossible to quantify. Oregon has had to confront flood-related losses as well. During the five-year period beginning 2013 through 2017, Oregon had 400 flood insurance claims under the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) with reported claims of $6,780,211 according to the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development. NFIP identifies 251 communities in Oregon as flood prone, including locations in all 36 counties, 212 cities, and 3 tribal nations.

Like so many issues, the impacts of flood events disproportionately fall upon Black communities and those impacts can exacerbate social and racial disparities already present. E&E News conducted an analysis of federal flood insurance payments that show flooding in the U.S. disproportionately harms African American neighborhoods, particularly those in urban areas. Why? As one expert said to the New York Times: Black families tend to be more exposed to flooding because their homes are often built on cheaper land in historically segregated areas.

The urban residents who are most vulnerable to flood damage—those who live in the lowest-lying areas or in neighborhoods without green space to absorb water—are often poor or members of minority groups. And, this has been proven here in Oregon time and time again.

In this case, history does repeat.

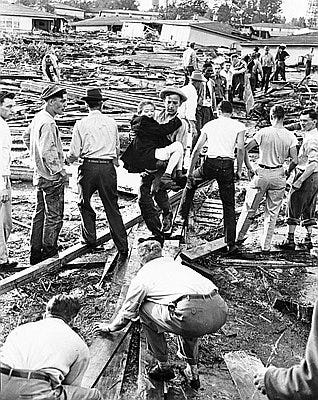

Carl Downey carries a woman to safety in aftermath of the Vanport flood, May 30, 1948. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi 3623.

Seventy two years ago, one of the worst flood events in Oregon history—the Vanport flood, destroyed an entire community that was home to a sizable portion of Portland’s Black families who lived there after redlining prevented them from living anywhere else. These families had an impossible choice: move or live where you’re family was threatened by flooding. When Vanport was swallowed by a swell of water, redlining pushed displaced Black families into a few Northeast Portland neighborhoods. Today, those neighborhoods have been greatly gentrified, and, yet again, pushed Black families further east where, to no one’s surprise, flood risk is greatest. Folks say that history doesn’t repeat, it only rhymes, but this story is the same one that’s played out throughout Oregon’s history.

The stats reinforce the story. A 2019 Portland State University study stated that residents in East Portland, where there is less vegetation, more traffic, and fewer trees and investments in green infrastructure, are most vulnerable to extreme weather including extreme heat and flooding. These are also the communities most likely to feel the deepest economic impacts from a flood disaster.

The disparities don’t end at exposure to disaster, marginalized communities also have a harder time recovering. The resources available to rebuild a home or business damaged by flood waters are not equal from zip code to zip code. A March 2019 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found that urban flooding effects are most harmful to minorities, low-income residents, and others without the resources to handle the damage and disruption. So, in short, Black communities are more likely to be impacted by floods and less likely to have the resources to recover. What can be done?

Where to go from here: policy suggestions

There are appropriate policy prescriptions to address this, but those prescriptions must be accompanied by efforts to address systemic injustice and inequity that have left Black communities segregated politically, geographically, and economically. They must also be accompanied by action on climate change. Unfortunately, each are encountering stiff opposition in some circles. In the meantime, there are common sense policies that can help business owners, families, and communities better prepare for floods:

Establish a federal flood disclosure requirement – While Oregon has existing disclosure laws, there is no federal requirement for sellers to disclose flood risk or history to potential property buyers. The lack of standard information perpetuates confusion and creates significant financial damage for homebuyers caught unaware of their true flood risk. For families living in a 100-year floodplain, the likelihood of a flood occurring during the lifetime of a 30-year mortgage is one in four. Disclosure laws already exist as a standard practice for property when it comes to lead paint—flood risk should be no different. More than 130 organizations and businesses agree and are calling for federal action.

Create a state revolving loan fund for flood mitigation – Legislation has been introduced in Congress that would create a partnership between the federal government and individual states to provide low-interest loans for projects that reduce flood risk and save lives and dollars. These activities could include raising and flood-proofing public buildings, businesses, and residences; improving stormwater management; assisting residents who wish to move out of harm’s way; and converting frequently flooded areas into parks and other recreation areas. Studies show that, on average, a dollar invested in disaster mitigation can save $6 in avoided future losses.

These are just a few of the policies that will make a real difference in preparing communities for flood events. We know that the horrible events of these past weeks may become more normal in the future.

It is important that we do what we can to prepare.

It is vital that we do what we can to minimize the environmental inequity being experience by communities of color.

It is imperative that we don’t wait for another disaster to strike.