David Frank: What happens when Oregonians have few good options

An analysis of how the lived experiences of residents in two counties are strongly correlated with electoral outcomes.

David Frank has been a professor at the University of Oregon since 1981. He is a resident faculty member in the Clark Honors College and is an affiliated faculty member in the department of English's program in rhetoric. He served as dean of the Clark Honors College from 2008 - 2013.

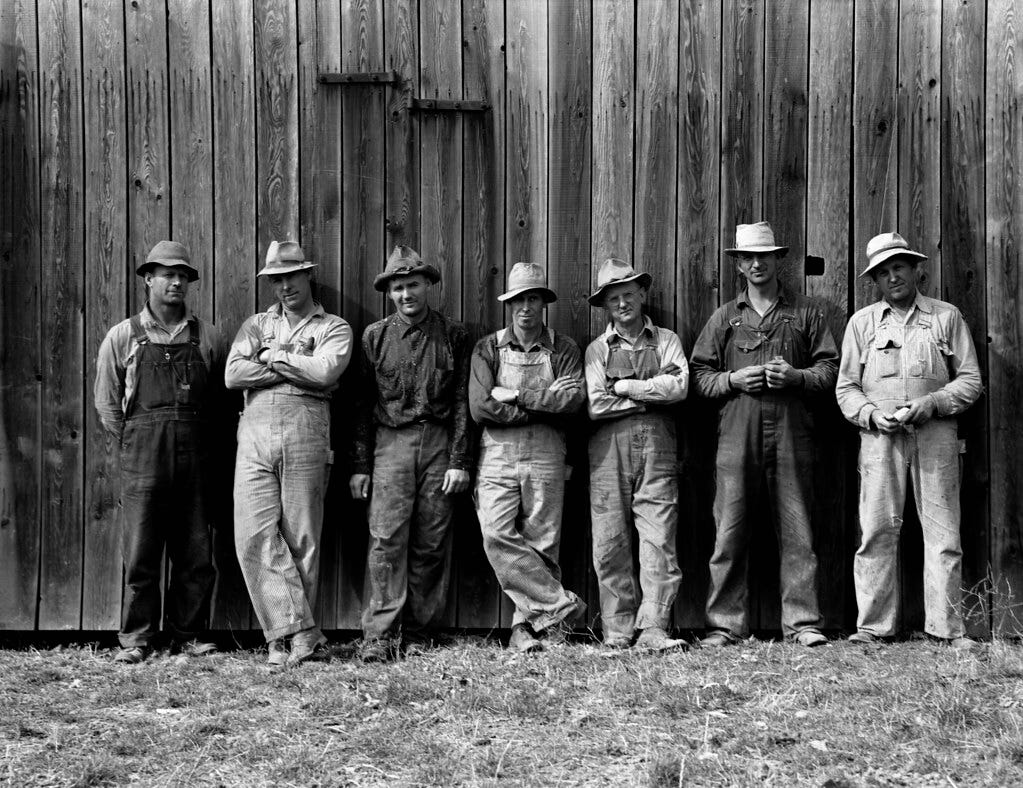

Three Sons of Oregon

"Dorothea Lange: Farmers who have bought machinery cooperatively, West Carlton, Yamhill County, Oregon, 1939" by trialsanderrors is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Jim Tankersley covers economics and tax policy for the New York Times. He graduated from McMinnville High School in 1996.

Nicholas Kristof, winner of two Pulitzer Prizes and New York Times op-ed columnist, graduated from Yamhill Carlton High School in 1977. Both high schools are in Yamhill County.

I served as a dean and as a professor at the University of Oregon. I graduated from South Salem High school in 1973. Salem is located in Marion County.

As sons of Oregon, the three of us are haunted – our home counties, Yamhill and Marion, voted for Trump in 2016, and may do so again in 2020. The specter is not about partisan outcomes, but decency, humility, and respect – all attributes ascribed to Republicans like Mark Hatfield and Democrats like Ted Kulongoski as well as other leaders that followed the Oregon Way. These three sons ask why Oregonians supported an individual with few of the traits at the core of our state’s leadership ethos and offer explanations that both overlap and diverge.

Three Investigations of How Oregonians Vote and Why

"Yamhill County Rancher Restores Native Oregon White Oak Habitat" by NRCS Oregon is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Tankersley, and Kristof with co-author Sheryl WuDunn, set forth their answers in books that should be required reading for Oregonians. In a recent presentation of his book, The Riches of the Land, for Powell’s Books, Tankersley invited listeners to concurrently read his book and Kristof and WuDunn’s Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope. The pair of books help explain why Oregonians in south and north Yamhill County yielded to Trump’s voice and vision. While the books find their origins in Yamhill County, they provide insights that are different, yet are complementary.

Tankersley, Kristof, and WuDunn agree that many citizens in Yamhill County have suffered from economic dislocation and cultural despair. The Riches of the Land features the rapid economic deterioration in Yamhill County; Tightrope highlights the cultural decline of Yamhill’s white working class. Read together, the two books provide excellent diagnosis of Yamhill County’s economic and cultural traumas, explain why Oregonians find Trump’s message persuasive, and offer policies that might reduce suffering in our state.

Tankersley’s McMinnville. Confessing that he “had lost touch” with McMinnville classmates while he “chased” and realized his dreams (which include a Stanford University degree), he returned to his hometown in search of answers to “the most important question in American public life today.” That question: “Where did the good jobs go for the American middle class, and where will we find new ones?” With his background in economics, Tankersley identifies “timber shock” as the answer to the question “Where did the good jobs go?”

McMinnville had once been a timber town. The fathers of Tankersley’s McMinnville classmates had secure jobs in timber mills, which provided middle class status. When Tankersley left McMinnville for Stanford, half of these jobs had disappeared due to automation, a recession, foreign imports, and environmental constraints. The “downfall of the timber industry” Tankersley concludes, taught him “how the economy could crush workers with almost no warning,” leaving his McMinnville and his classmates in the wake of an economic disaster. They blame environmental policies, government, and the urban centers for a failure to address rural problems, which Trump addressed in his 2015-2016 campaign.

Kristof and WuDunn’s Yamhill. Kristof, like Tankersley, went in search of classmates he had left behind. In collaboration with WuDunn, he sought out Yamhill

friends who used the Number 6 Yamhill school bus route to Yamhill schools. They found that economic and cultural forces had created “heartbreaking” suffering for Kristof’s classmates. Kristof and WuDunn rehearse the economic explanations for this suffering offered by Tankersley – factories and jobs in northern Yamhill County evaporated after Kristof left for Harvard University, with almost no recognition or balm offered by government or society.

Lacking the economic touchstones necessary for a middle class, cultural well-being in Yamhill collapsed. The result: what Princeton University scholars Anne Case and Augus Deaton term “deaths of despair.” Citizens of Yamhill, Kristof and WuDunn write, turned to suicide, drugs, and alcohol. With sadness and great empathy, Kristof and WuDunn see a “trajectory of the …kids on Number 6 school bus” from life to deaths of despair. As important, many of those suffering in Yamhill feel disrespected, left behind, and forgotten.

Frank’s Salem. My high school class was quite large. Salem was and is a conservative town, but it does not possess, like McMinnville or Yamhill, a rural consciousness. The preferred politics in Salem was – and remains – Republican and conservative, although it was still possible, when I was in grade school, for Mark Hatfield, who served as a U.S. Senator, to embrace moderate positions.

Race, a theme developed by Tankersley, Kristof and WuDunn, was not much discussed at South Salem High School, as almost all of its students in the early 1970s were white. Oregon remains a predominately white state, as Tankersley, Kristof and WuDunn, note, because of its racist history. This history begins with Matthew Deady, who was elected to represent Yamhill County as an Oregon legislative assembly delegate. He attended the Oregon Constitutional Convention in 1857 as a pro-slavery delegate and helped write the Oregon Constitution that banned African Americans from the state. Oregon’s white demographic is one of Deady’s legacies. Until the George Floyd murder sparked protests on the University of Oregon campus, the oldest building at the school was named after Deady.

I remember campaigning, during the 1972 Presidential election, in the wealthy Candalaria district of Salem, for George McGovern. Most of the voters supported the war in Vietnam, were against welfare, and declared their support for Nixon. Some of the Facebook posts made by my high school classmates in support of Trump reflect these patterns. I am heartbroken to see them display of a profound lack of knowledge about racial trauma, taxation, and foreign affairs. One of my closest friends in high school, whom I have not seen in twenty years, wears a red MAGA hat in his profile. Most troubling is the expression of hatred and contempt for anything smacking of racial tolerance, taxation, or Biden. It’s not wrong to disagree on politics (in fact, it’s healthy to have a robust civic discourse), but supporting those that demean others is, among other things, far from the “Oregon Nice” mentality that many Oregonians try to uphold.

Why Oregonians Will Cast Very Different Votes in November

"1920. Scouting and mapping areas of beetle kill from a high point. Jenny Creek, Oregon." by USDA Forest Service is marked with CC PDM 1.0

In returning to the original questions: Why did Yamhill and Marion counties vote for Trump in 2016 and may do so again in 2020? The Riches of the Land, Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope, and my experience suggest the following answers: First, the citizens of Yamhill County (and other timber counties) experienced “timber shock” and subsequent economic dislocations. Donald Trump spoke directly to these concerns when he declared at a May 7, 2016 rally in Eugene that he would bring timber mills and jobs back to Oregon. His opposition to “bad trade deals” like NAFTA, the entrance of China into the World Trade Organization, promotion of protectionism, and a commitment to rebuild the manufacturing base is quite persuasive to this audience.

Second, the citizens of Yamhill and Marion counties, as well as those in Eastern Oregon, feel disrespected by the urban elite in Portland, by the government in Salem, and by the media. Trump, in celebrating nationalism and promoting white identity politics, confronts this perceived disrespect. His rallies and rhetoric create a sense of community and a rejuvenated purpose. I attended a Trump rally earlier this year in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Both Trump and his audience freely used the word “love” and there were many upward inflected emotional moments of affirmation.

Third, timber shock and the perceptions of disrespect seem to activate a contempt for Democrats, national media, progressive positions on race, taxation, and a host of other issues. Unfortunately, progressive politicians have fed these perceptions with Barack Obama stating at an event in 2008 that people in rural areas “get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren't like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations." Obama’s statement was compounded by Hillary Clinton’s declaration that “half of Trump’s supporters” should be grouped “into what I call the basket of deplorables.” They are “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic—you name it.”

Giving Oregonians Better Options

Tankersley and Kristof share my love for Oregon and its citizens. In search of solutions, Tankersley offers a menu of economic policy options that would help address our collective failure to create the conditions necessary for a fair and flourishing economy. The inspiration for his policies is anchored in “Prayer for the Oppressed,” taken from The Book of Common Prayer, which he and his family used when they attended St. Barnabas Church in McMinnville. The prayer calls for equal opportunities for all and the elimination of cruelty. Similarly, Kristof and WuDunn identify ten steps that would reduce suffering, doing so by anchoring them in empathy for others. In addition to economic reformation and greater empathy, higher education can play a major role in addressing economic and identity issues. I have taught the history of the civil rights movement in Deady Hall and have witnessed students from rural areas in Oregon coming to terms with our state’s original sin.

There is, always, a chance for reversal. Columbia and Tillamook counties voted twice for Obama and the flipped to Trump. With a proper dose of economic policy, empathy, and education, citizens of Columbia and Tillamook might change their votes. Similarly, just a small change in the voting behavior of citizens living Yamhill and Marion counties could make a difference. Less than 4,000 votes separated Trump from Clinton in Yamhill county (out of 40,000 votes) and Trump won Marion county by less than 6,000 votes (out of 102,000 votes).