David Frank: Kristof’s Lament: A Friendly Quarrel with Eric Ward

This disagreement is a friendly quarrel, one between like-minded Oregonians committed to developing an Oregon Way designed to inoculate against and root out white nationalism.

David Frank has been a professor at the University of Oregon since 1981. He is a resident faculty member in the Clark Honors College and is an affiliated faculty member in the department of English's program in rhetoric. He served as dean of the Clark Honors College from 2008 - 2013.

Eric Ward’s January 15, 2021, contribution to the Oregon Way blog is an eloquent, thoughtful essay on what Oregonians should do to excise the cancer of white nationalism from our state. To his great credit, Ward is an antiracism leader, serving as a Senior Fellow of the Southern Poverty Law Center and in a host of other positions of influence. He accurately describes the rise of white nationalism and the toxic consequences left in its wake, and he rightly argues that our state and country “can no longer afford to take a bystander role in the battle of control over and within the Republican Party.”

Ward offers readers of Oregon Way steps Oregonians can take to confront white nationalism, a social cancer that has a deep history in our state and remains an active force. The major step he advocates to confront white nationalism is training sessions featuring the history of white supremacy in Oregon, the tools needed to identify white racism, and the need to institute antiracist expectations and practices.

As an example, he points to a training session, held on September 26 and October 6, 2020, that he oversaw for Portland’s governmental leaders. By all accounts, it was a successful training, one that the Portland City Council and city bureau directors celebrated as an effective effort to help Portland governmental leaders combat white supremacy.

I applaud Ward’s success in training Portland governmental leaders; nevertheless, I disagree with the emphasis he places on antiracism training as the first and primary focus in our shared battle with white nationalism. This disagreement is meant to be a friendly quarrel—I admit that Ward may be right.

Nicholas Kristof’s January 27, 2021 column in the New York Times and my experience living in Oregon for fifty years prompts my friendly quarrel. Kristof, born and raised in Yamhill, keeps in touch with his Yamhill High School friends and dedicated his latest book Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope (coauthored with Sheryl WuDunn) to a study of Yamhill’s economic and cultural decline.

Kristof, in his January column, noted that he had returned to Yamhill in early January 2021. He learned, with some horror, that his “old pro-Trump friends” thought they were in “danger now” that Biden and the Democrats were in power. That danger: Trump voters would be sent to “re-education camps” designed to cleanse them of offending beliefs. Kristof laments the influence of the “right-wing echo chamber” that introduced and fed his pro-Trump’s friends’ fears with fantasies about “re-education camps” and “cancel culture.”

I doubt that Ward’s laudable anti-white supremacy trainings would work with Kristof’s “old pro-Trump friends.” Indeed, training programs designed with the admirable goal of countering white nationalism could appear to Kristof’s old pro-Trump friends in Yamhill as an effort to “re-educate.” I fear such efforts may not only fail but might be counterproductive. Ward is right to highlight education as one method we can use to confront white nationalism, but it should be nested within, and often subordinated to, other approaches, given the audience attracted to this odious doctrine.

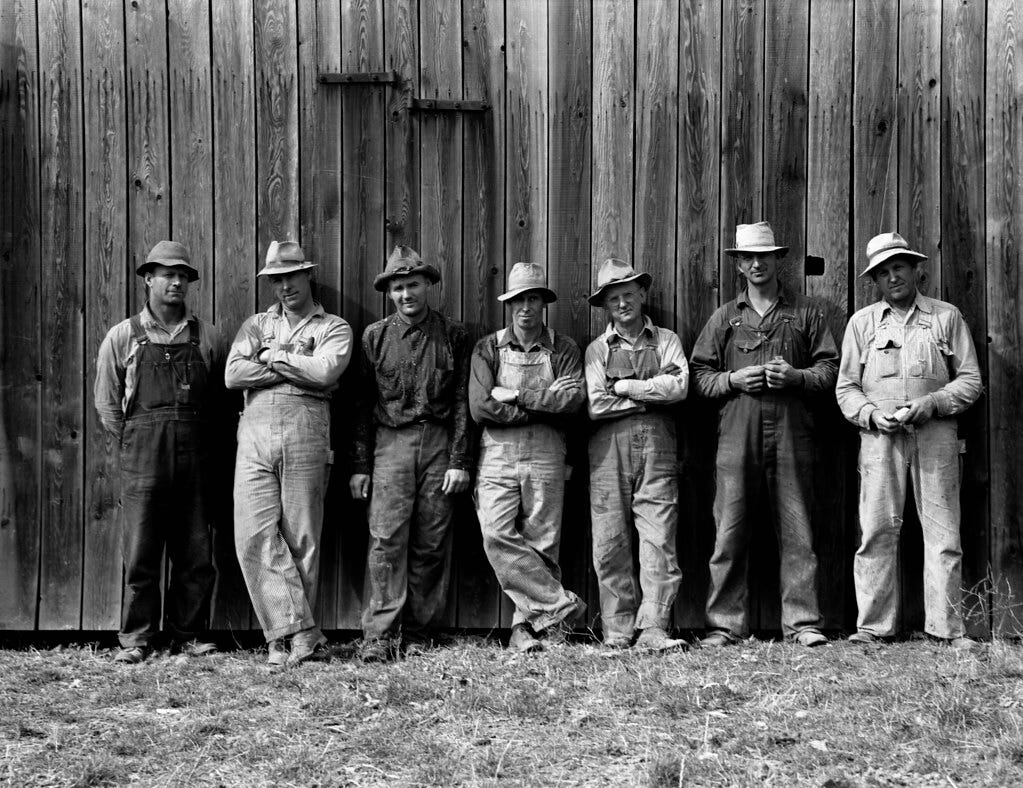

In Tightrope, Kristof and WuDunn offer a comprehensive survey of the economic and cultural factors explaining Yamhill’s decline and that of the white working class since Kristof graduated from Yamhill High School in 1977. The rise of white nationalism and Trumpism follows from economic decline and cultural disrespect. The white working class in Yamhill and the United States has, in the last forty years, been hit with the economic tornadoes of globalization and automation, undermining its financial security and hope for the future.

Democrats and the progressive left too often portray the white working class’s gravitation to conservative and regressive outlooks as evidence that they are “cling[ing] to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations” (Barack Obama) and that half of Donald Trump’s supporters belong in a “basket of deplorables” (Hillary Clinton). Donald Trump responded by declaring to his base that the Democrats and left “hate our country” and “they hate you.”

Yamhill County voted for the Trump-Pence ticket in both 2016 and 2020. Kristof and WuDunn rightly note that “many ballots cast for Trump” should be understood as “a primal scream of desperation because they felt forgotten, neglected and scorned by traditional politicians.” They document in their book that the widespread “deaths of despair” disease, afflicting the white working class in rural areas, is conspicuous in Yamhill.

“The despair,” they write, “arises in part from frustrations about loss of status, loss of good jobs, loss of hope for one’s kids.” They cite the research of Nobel Prize-winning Angus Deaton and his colleague Anne Case that explains why drugs, alcohol, and suicides, the result of economic and cultural forces of declines, have elevated the death rates of the white working class above those of many minorities. White nationalism is born out of economic despair and threat to identity.

Anti-white supremacy trainings, as I understand them, would not address many of these factors. The white working class does not see itself as benefiting from white privilege, a notion often at the center of antiracism training. Kristof and WuDunn offer an approach with a different agenda and emphasis. As they write,

There’s sometimes an impulse to pit the suffering of the white working class against that of African Americans or members of other minority groups. That is a mistake. Government policies have poorly served the working class of every complexion, and we need solidarity rather than strife among those so overlooked.

In pursuing better government policies, we need plans addressing the suffering of black and white, rural and urban Oregonians, folding them into a more perfect union.

We need vaccines designed to counter the disease of white nationalism. These vaccines should take the form of economic investment, displays of cultural respect, and better systems of communication. Toward this end, we need policies that share the wealth and capital of Portland and the Willamette Valley with Oregon’s rural communities and families.

The concerns of Hermiston, John Day, and Klamath Falls should be on par with those of Portland, Salem, and Eugene. Could Nike, for example, target Oregon’s rural areas for the production of their products rather than the Uyghurs, who are forced into labor camps by the Chinese government? Could the State of Oregon create a “Digital Oregon Trail,” as advocated by Kevin Frazier, to expand broadband high-speed access to Oregon’s rural areas?

A carefully constructed anti-white supremacy education that does not demonize whites and the white working class could be a good, but subordinated, complement to government policies that address economic insecurity and cultural isolation. The race-class narrative framework, used in North Carolina, Minnesota, Michigan and Pennsylvania by progressive activists, stresses deep conversations based on empathic and non-judgmental listening, and provides evidence that citizens living in rural areas respond positively to carefully crafted messages joining progressive economic policies with race-conscious messages.

I have no doubt that Eric Ward would agree with the need to embrace the concerns of Oregon’s white working class. He may disagree with my subordination of anti-white supremacy education. This disagreement is a friendly quarrel, one between like-minded Oregonians committed to developing an Oregon Way designed to inoculate against and root out the disease of white nationalism.

*********************************

Keep the conversation going:

Facebook (facebook.com/oregonway)

Twitter (@the_oregon_way)

Check out our podcast: