From a Veteran's Daughter

If I could share one lesson with the American classroom on this Veterans Day, it is this: It is possible to adopt a mindset within which you can simultaneously respect and critique an idea.

I am a 6-year Oregon resident. We moved here for the rainy weather and the green; we stayed because of the beautiful community we found.

This Veterans Day, I will rise early and put out my American flag, as I have done every year of my life on the various days of remembrance. I will sit in contemplation, thinking about my dad and all of the veterans who have made both the ultimate sacrifice and a thousand other sacrifices to ensure our domestic tranquility. I will pray for the safety and protection of our 1.3 million active duty and 800,000 reserve military service personnel, while I also pray that they bring peace and improvement to the areas of the world to which they have been posted. Some people might think that praying for peace while honoring those who prepare for war is paradoxical or even hypocritical. I would remind those folks of what F. Scott Fitzgerald said: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

The recent election indicates that Americans may have all but lost this ability, with half the country believing the other half will most assuredly usher in total destruction if given power. The clash of such rigid belief systems feels dangerous, but also, ripe with what we used to call in education a “teachable moment.”

Accepting a complicated world

If I could share one lesson with the American classroom on this Veterans Day, it is this: It is possible to adopt a mindset within which you can simultaneously respect and critique an institution, idea, or belief system. And in that in-between space, we can find real and lasting solutions to problems that we all face. It starts with believing that our fellow Americans are essentially good, and that we don't live in a world of cartoon villains. It requires us to have empathy and attempt to understand where the other person is coming from. It requires us to refrain from accusation, and instead ask questions and listen to answers, even if they make us uncomfortable. It requires each of us to be of service to each other, and to make improvements wherever we find ourselves.

This is a mindset I learned from my mom and dad and our military family friends, who while fully inhabiting and benefitting from an institution, the U.S. Military, simultaneously critiqued and found ways to improve it while they were in it. Military service demands discipline, self-control, and patience above all else. As my dad often said, “90% of the job is mopping up, kid. That’s why it’s called ‘the service.’”

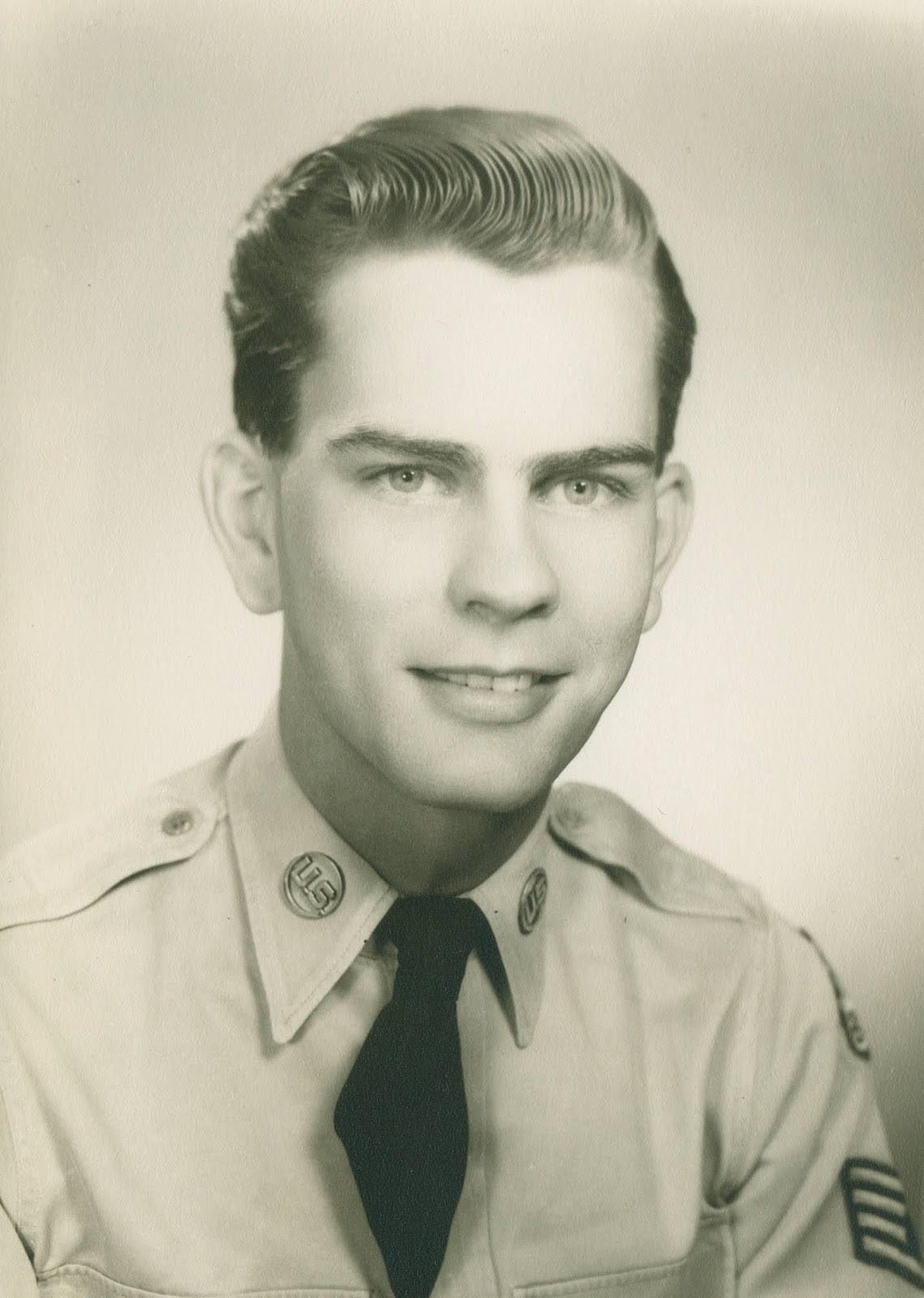

My dad was never very “gung-ho” about being in the military. If anything, he was an ambivalent soldier. He came to the military like so many young people do: he was dying to get out of his small town. Having lost a favorite uncle at Pearl Harbor, there was also a not-so-small motivation to join in a fight that he didn’t even clearly understand yet. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1948 on his 18th birthday, two months before graduation. With dreams of becoming a pilot, he left his small town of Lake City, Iowa, bound for Korea. A last-minute change of orders sent him to Japan instead, where he was assigned to be trained as an MP (military police.) “Hey, I didn’t sign up to be a COP!” was his snarky, teenaged reply to that order, which earned him several months of sleeping in a tent and peeling potatoes. When that didn’t change his mind, his Commanding Officer (CO) directed him to find a way to clean, sort, and inventory a mountain of machine parts that had busted out of crates and were covered in a thick layer of cosmoline. He was introduced to a crew of local Japanese civilians who could help, but who didn’t speak English. Three weeks later, my dad, who now spoke some passable Japanese, presented his CO with a typed list of parts that had been cleaned (Dad had worked with the Japanese civilians to cook up a home-made surfactant to clean the parts,) sorted, and labeled. The CO looked over the list in disbelief. He nodded and said, “So you can TYPE, eh?” And that’s how my dad ended up in the office pool, where he met a certain sassy, smart, auburn-haired beauty from Philadelphia. The rest is, shall we say, history.

In the ensuing decades, my parents remained ambivalent toward the military, while still steadfastly applying their full selves to being contributors to their community. Notably, they continued to contribute despite hardships and sacrifices. On their first wedding anniversary, Dad got orders for the nuclear weapons testing going on in the US Marshall Islands. He sent his new bride and baby girl home to Philly to live with relatives while he went off to an uncertain posting. Stationed at Kwajalein Island, Dad witnessed the detonation of the world’s first hydrogen bomb. Operation Ivy’s bomb, codenamed “Mike” for “megaton,” was 700 times more powerful than the one that had destroyed Hiroshima. To date, it is still the 4th largest nuclear weapon ever detonated by the U.S. It obliterated the island of Elugelab, leaving a crater a mile wide and 17 stories deep. Eyewitnesses said they were instructed to hide in a foxhole and cover their eyes. The blast was so bright, though, that through their closed eyelids, they could see the bones in their hands.

Dad was sent home from Kwajalein in 1953 with an armful of mysterious tumors. Amputation seemed imminent. His arm was saved by a visiting orthopedic surgeon at Walter Reed Hospital. There he convalesced alongside combat veterans who had lost limbs, eyes, and hearing. There were men burned beyond all recognition, yet still alive. My mother made daily visits and read to the men and wrote letters home to their mothers and sweethearts while holding back her tears. The experience was transformational for both of them. That was the first time my dad considered leaving the military. Feeling a new lease on life, he wanted to go home with his wife and baby more than anything. However, his recent stint at Kwajalein put him in line for a promotion and a transfer to weapons testing in New Mexico. So, once again, off they went.

Over the course of their military career, my mom and dad moved over 15 times and lived in eight different states and four different countries. Only two of my seven siblings were born in the same state. Some of them went to four different high schools, one for each year. Despite a few attempts to leave the military and return to civilian life—he once said in a letter that he hadn’t chosen his military career; it had grown “like a fungus”—my dad stayed in. Even though he disagreed at times with colleagues and policies, my dad strived to improve the places where he worked. As a result, he continued to be promoted, even though he was not a college graduate. The military provided a salary that my dad could never have hoped to earn in the private sector. Of course, the financial gains came at a personal cost—his service kept him away from us for long periods of time.

Serving in two capacities: soldier and dad

We all knew our dad was a soldier, but at the end of the day (or month, or year,) he came home to us and we peeled off the layers of his military life—removing his stinky boots was MY special chore—returning to us our daddy, and the love of my mom’s life. At home, this never-once- dinged-on-inspection, tactical supply and logistics expert was mercilessly defeated by our messes, our laughter, our squabbles, and the rolling eyes of his sweetheart. My father may have been a top-rate officer, but he was utterly powerless against the army of his family. He lived in two worlds that often crossed over into each other: he tried valiantly but futilely to make our house “shipshape.” Later, back on base, his other world would appear unexpectedly—like when he was surprised by a pair of his teenage daughter’s stockings appearing in the collar of his uniform while he was interviewing a young recruit. The bounce back and forth between those two worlds made him a perpetually grouchy, lovable, and, ultimately, human hero.

Dad’s last overseas posting was in Vietnam, from 1971-72. He spent that year at Tan Son Nhut Air Base near Saigon. It was a surprising posting for a 20+ year veteran with eight kids, but his skills were needed. He was there for the infamous Easter Offensive, when the U.S. forces helped to orchestrate more than 20,000 strikes against the invading North Vietnamese army. It was a miserable period with over 140,000 casualties spread over both sides.

Meanwhile, the family was posted stateside at Hamilton Air Force Base, across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, then a hotbed of anti-war protest. My oldest sisters and even my mom began speaking out against the war in Vietnam. My mom wrote letter after letter to my dad, driven mad with worry and angry at a war that seemed pointless and endless. My uncles, stationed nearby at Travis Air Force Base, were furious with her. Debates ensued. Tables were pounded. Things got a little hairy. But ultimately, our family got through that difficult time and learned from it. Over the years, attitudes changed. Apologies were made. Relationships were repaired. All of the adults in my life modeled for me that disagreements are not deal breakers, and for that I am so grateful. My parents never stopped trying to change minds, and having their minds changed.

We are all much more than a single identity

Dad retired in 1976 and he and my mom bought an almond farm in California’s Central Valley. The rows of trees with their neat precision spoke to both his farm-boy roots and military sensibilities. Those years on our almond farm remain the most vibrant, joyful years of my childhood. My dad and I walked the rows and talked a lot. I had a completely different relationship with him than the rest of my siblings, having been born nine years after my youngest sister. He told me stories about the war when I asked, but mostly he kept those painful memories to himself.

My dad never joined the VFW or the civilian corps to work on base, like many of his fellow soldiers did. When he left the military he was DONE. He shed that life as quickly as he’d once shed his fatigues and boots, and for once, he was at peace: a good farmer, a good businessman, a good dad.

I think that my father said best what I feel in my heart as an American, as the daughter of a soldier, and as a person who seeks peace above all:

The misery war causes goes far beyond what the human mind can comprehend even when you see it. The dead must be the only real winners. I saw enough misery the past two days to last a lifetime. I’ve seen as bad before I guess, but when you get older, I think you get softer - not harder. My old heart is bleeding, but little good it does. I will never understand why God doesn’t wrap it all up and throw this old world into hell. Then I think of you and my children and all the good people I know and realize that it’s for you too. Why would God want to destroy my loved ones? Love me my darlings. Love one another and be assured I love you all and miss you.

Letter from Dad in Vietnam, June 1972

Please join me in thanking our veterans and active duty service personnel, for their sacrifices are beyond the comprehension of most civilians. They inhabit two worlds simultaneously, one where they must constantly be prepared for war, and one in which they work for peace. We have much to learn from them, and we owe them a nation of patient, careful thinkers. Let us be of service to each other, so that they can serve us proudly.

*****************************************************

Keep the conversation going: Facebook (facebook.com/oregonway), Twitter (@the_oregon_way)

#61