How will the strikes of 2023 affect 2024 and beyond?

Labor unions rarely have had a year as successful as 2023, but workers’ future depends more on shifts in technology and the economy than their contracts

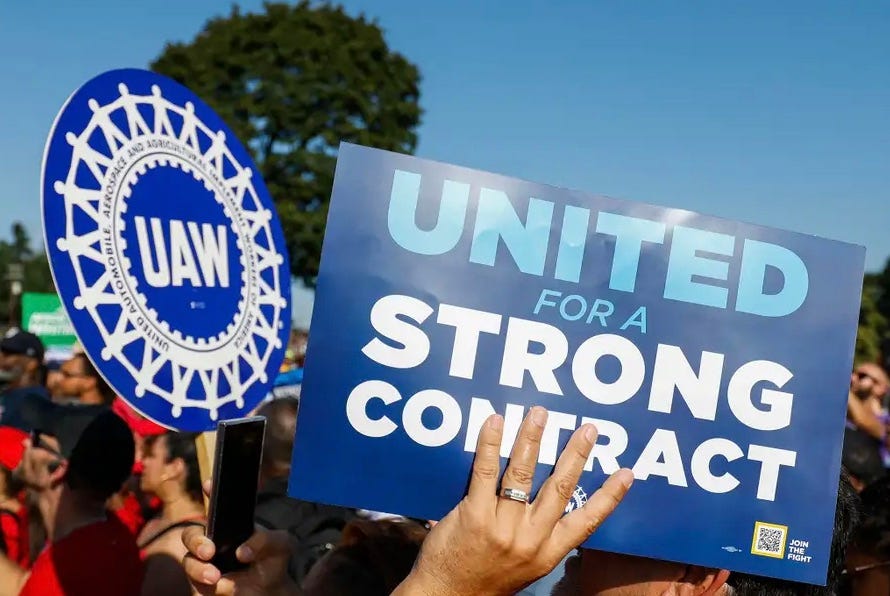

The labor movement had its most active year in decades in 2023. Through early October, there had been 312 strikes nationally, affecting more than 450,000 workers. Not since the early 1980s has the U.S. seen as much strike activity as it has in 2023, according to a CNBC article.

Not only were strikes numerous, but they also were meaningful. Striking autoworkers and Hollywood writers gained worldwide attention and won significant concessions that could have long-term ramifications on their industries. Locally, Portland teachers drew national attention with a script of that has been used in other West Coast urban school districts and likely will be applied elsewhere, emphasizing class-size reductions and more effective student discipline in addition to pay raises.

Only time will tell who, if anyone, got the better end of the contracts these strikes produced. But it already is clear that the negotiations in the highest-profile strikes established some precedents that likely will resonate beyond the workers and companies directly affected.

In the three strikes mentioned above, management and workers landed in between each side’s original offer on wages. That’s what almost always happens. Setting wages is what collective bargaining does best. But wages were not the only issue, nor the most contentious, in any of these strikes. Here are two issues that were at the center of these negotiations and likely will continue to be in future labor negotiations – with or without strikes.

Work conditions

The Covid-19 pandemic focus attention on work conditions in a variety of ways. Most notably, it forced employers to allow many employees to work from home, an arrangement that many workers want to keep at least part of the time. It also magnified the importance of health care, childcare, flexible schedules and other benefits that workers always desired but gained more ability to demand.

These and other workplace issues were at the forefront of negotiations to end the highest profile strikes of 2023.

According to reports, one of the final sticking points in the Portland teachers strike was classroom size, which is a quality of work issues for teachers that conflicts with efforts to secure the highest wage possible when dealing with finite financial resources. Workplace issues as diverse as how to deal with unruly student behavior and the condition of school heating and cooling systems also were part of negotiations.

Similarly, the writers union successfully pushed for minimum staffing levels for the writers rooms where scripts for television shows are created.

Autoworkers were less successful on workplace issues, failing to secure their signature demand of a four-day work week. However, they got the biggest pay increases of the high-profile strikes and convinced Stellantis to reopen a plant, a rare concession by an employer.

Unions have taken a two-pronged approach to seeking improved work conditions, making them a priority in both collective bargaining and legislative lobbying. They’ve had significant success but much of it has been geographic. Lobbying victories have come mostly in states where Democrats control the Legislature and Statehouse. Those, not coincidentally, are the same states where strikes are the most successful. It seems likely that the differences in rules between states will widen, which could tempt more companies to open plants in states with rules they prefer.

Control of the future

Unions always have sought to protect jobs against economic cycles and future technological threats. But rarely have the threats been as specifically defined as they are now.

In the autoworkers strike, the issue was electric vehicles. in the writers strike, the issues were streaming and artificial intelligence. In the teachers strike, the issues were less directly tied to technological advances. But remote instruction and education alternatives made possible by technology lurked in the background. Interestingly, concerns about students abusing artificial intelligence didn’t appear to be a contentious issue in bargaining.

Workers gained significant concessions in all these negotiations. The question is whether companies can deliver what they promised and state in business.

I once worked for an employer that had a job-for-life guarantee. Unlike many of my co-workers, I wasn’t upset when that pledge was broken because I knew the company was promising something it couldn’t control. I was surprised that the newspaper business declined as rapidly as it did and disagreed with some of the decisions that were made, but I also knew that no employer is immune to the broader forces of the economy, technology and competition. Sometimes your employers loses and you do to.

That’s a lesson that unions must learn if the recent strikes are going to produce long-term economic gains instead of just a short-term negotiating victory. Likewise, management must accept that they and labor must agree on the right decisions and execute them together if their companies are going to survive in a rapidly changing competitive landscape.

Mark Hester is a retired journalist who worked 20 years at The Oregonian in positions including business editor, sports editor and editorial writer.

I noticed that teachers sacrificed smaller classes for higher wages and more unscheduled time for teachers. Less work, more pay.