Jim Moore: The "Way" Back in the Day

The Oregon Way as It Was Fifty Years Ago—How Eighteen-Year-Olds Got the Right to Vote

Longtime observer of Oregon and west coast politics. Political analyst for various media outlets, professor at Pacific University.

(This is an edited excerpt from a much larger project on Governor Vic Atiyeh.)

The 1971 Oregon legislative session created the Bottle Bill, started the discussion about ethics rules in Oregon government, and voted for eighteen-year-olds to have the right to vote. These hallmarks of the McCall era and what came to be called the Oregon Way are still important to us today. It was McCall’s era, but those in the legislature felt they were doing the heavy lifting while McCall was bringing public opinion around to these big issues.

The session started out with a leadership battle in the Oregon Senate. It took eleven days before a coalition of the fourteen Republicans and two conservative Democrats finally selected John Burns (D-Portland) as the President of the Senate. The key to this story is that before 1973, the president of the Senate became acting governor whenever the governor left the state.

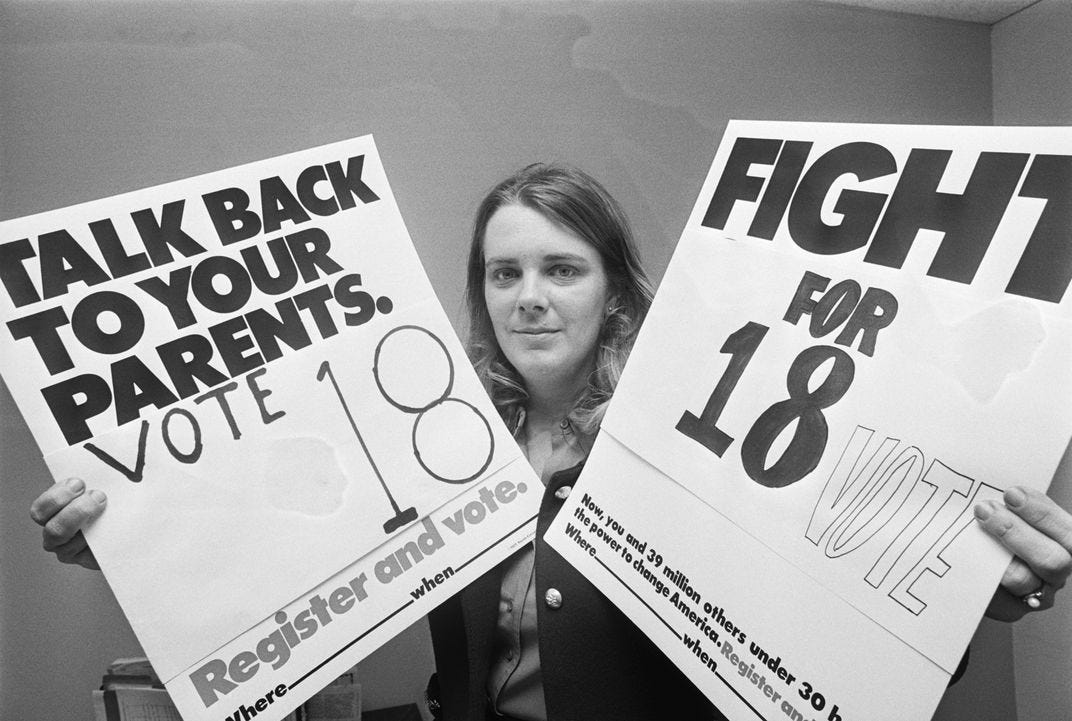

The Oregon legislature had voted several times on lowering the voting age. The bills failed in 1967 and 1969, and in May 1970 the people of Oregon soundly defeated a ballot measure generated by the legislature to lower the voting age to nineteen. In February 1971, the Oregon Senate once again passed a bill to lower the voting age—if the House passed it as well, it would go back out to a vote of the people in 1972.

A similar debate was going on at the national level. Congress voted to lower the voting age in 1970, but it became clear that it would take a constitutional amendment to make this stick for all federal, state, and local elections. By March 1971, the Congress had overwhelmingly passed the constitutional amendment and it went out to the states for ratification.

In Oregon, focus switched from the Oregon solution (aiming at the 1972 ballot box) to the national solution, and the House passed the national amendment. But, as the session was drawing to a close at the end of May, the Senate had still not acted on it. It was at this point that the ‘sausage making’ characteristic of the Oregon Way—how to achieve ends that advance our political goals when principles collide—became clear.

The key Senate committee was the Elections and Reapportionment Committee. It took three affirmative votes from the five-person committee to send a bill on to the floor of the Senate. Two members were absent, and one of the three remaining was opposed to the bill. Things did not look good.

A very interested observer at the time was a young Earl Blumenauer. He had been advocating for lowering the voting age while he was an undergrad at Lewis and Clark. Graduating in 1970, he was lobbying hard for either the state solution or the newly available U.S. Constitutional amendment. He tells the story like this:

The rules at the time were that the governor had to be physically in the state in order to be able to govern. When the governor left the state, the president of the Senate became the acting governor. McCall was out of state, so John Burns became governor. As part of the negotiations about running the Senate, the conservative Democrats in the coalition had actually allowed Democrat Harry Boivin to be president pro tem of the Senate. “Harry ‘The Fox’ Boivin” was the chair of the committee.

Blumenauer and the other young supporters of the bill were at the back of the hearing room. Blumenauer thought it was Representative Harvey Akeson (D-Multnomah) who said, “If I were Senate President, I’d fix this Committee.” Blumenauer described this as hanging in the air as people figured out that Harry Boivin actually was the Senate President because Burns was the acting governor. So, in a quick change, Boivin appointed two new people to the committee to get a majority and the bill came out of committee and went to the floor of the Senate.

“All hell broke loose,” according to Blumenauer, and “not just because of the voting age, which they were incensed about, but just thinking about what damage could the Democrats then do with a 15–14 majority in the State Senate.” There were fears that committees would be re-formed, and bills would be moved that had been safely relegated to certain committees to die.

An incensed John Burns—who favored the eighteen-year-old franchise—declared that Boivin’s actions “violated the integrity of the Senate,” and asked that the full committee meet again on the measure. The meeting duly took place, but two supporters of the bill, including Boivin, were missing, so the bill failed to get the three votes to go to the floor. Burns finally resolved the impasse by appointing himself to the Elections Committee, thus giving the bill the three votes it needed to make it to the floor.

The collision in principles was stark. Republicans, some of whom favored lowering the voting age, argued that Oregon’s people had spoken, and to go ahead with the measure “is telling the people ‘It doesn’t make any difference what you vote on. We’re going to do what we want here.’” The Democratic counterargument was twofold: referral of a U.S. Constitutional amendment to the people was unconstitutional in itself; and, extending the franchise was the right thing to do. Senate President “Burns took the unusual step of leaving the rostrum so he could become the principal spokesman on the Senate floor for the ratification measure.” In the end, and rather dramatically, George Wingard (R-Eugene), second to the last senator in the alphabetical roll call, voted yea, so the bill passed 16-14 (the other conservative Democrat, as usual in partisan fights, voted with the Republicans).

By the end of June, the requisite number of states had ratified the 26th Amendment to the Constitution. The time from passage out of Congress to ratification was a record three months, half the time of the previous record. If Oregon had not ratified the amendment, it still would have gone into effect. The thirty-ninth state to ratify (what would have been the decisive thirty-eighth without Oregon’s approval), passed the amendment on July 1, 1971.

Fifty years later, my students at Pacific University wonder that eighteen-year-olds were ever denied the right to vote. At the time, it was a monumental change. Oregon voter registration between 1970 and 1972 increased by the highest rate in the last 60 years—25.3%. Younger people got deeply involved in politics. Fifty percent of the members of the 1973 Oregon House were forty or younger, and ten of them were younger than thirty. And a young Earl Blumenauer was elected to the Oregon House in 1972 at age twenty-four, beginning a career in public service that continues to this day.

***********************************************

Keep the conversation going:

Facebook (facebook.com/oregonway), Twitter (@the_oregon_way)