Oregon Has Too Many Counties

Suggestions for how to make an administrative unit of government better at its intended purpose: serving people.

Andy Kerr consults on environmental and conservation issues. He is best known for his two decades with the Oregon Wild (then Oregon Natural Resources Council), the organization best known for having brought you the northern spotted owl.

Thirty-six is not a magic number, even if Oregon has eighteen counties on each side of the Cascade Crest (save a bit of boundary crest–missing, straight-lining between Klamath and Jackson Counties). In fact, fewer, more populous counties would result in more efficient use of tax dollars. Counties with larger populations are more efficient than counties with smaller populations at delivering services to their residents. Combining counties is a way to make them more efficient.

Some Oregon counties have so little population that they becoming, if not already are, unviable. Several years back, Wheeler County—Oregon’s smallest—pondered merging with Grant County, from whence part of Wheeler County came. Grant County wasn’t interested. I don’t know if Wheelerians made entreaties to Gilliam and Crook Counties, parts of which from whence Wheeler was carved.

The Counties: Their History and Vital Statistics

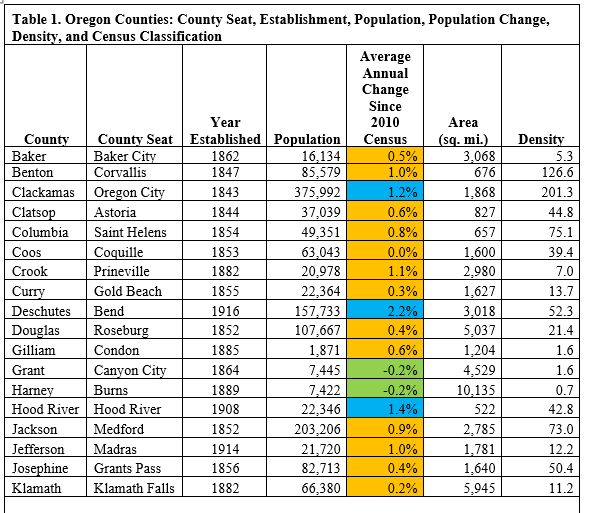

The first four Oregon counties were established on July 5, 1843 (Figure 1). The last Oregon county to be established was Deschutes County in 1916, more than a century ago, just before World War I. (Here’s are interesting, instructive, and iterative maps of the evolution of Oregon counties, from which Figure 1 was lifted.)

The present thirty-six Oregon counties range in population from 1,441 (Wheeler) to 735,334 (Multnomah), in land area from 435 (Multnomah) to 10,135 (Harney) square miles, and in population density from 0.7 (Harney) to 1,690.4 (Multnomah) people per square mile (see Table 1).

The Case for Combining Counties

Counties are not to states as states are to these United States. States and the United States are all sovereign governments. Counties are mere administrative subdivisions of the sovereign state and exist for the convenience of and at the pleasure of the state. Nor do counties have the enduring status of cities, which are incorporated and in Oregon range in population from 2 (Greenhorn) in Grant and Baker Counties to 664,605 (Portland) in Multnomah, Clackamas, and Washington Counties. A municipal corporation can go bankrupt; a county cannot.

Counties exist as mechanisms to provide services to the state’s citizens. Counties with small populations are inefficient at delivering services to residents. The larger the county population, the more efficient is the delivery of county services. Counties with populations of 20,000 or less (there are nine in Oregon, at least five of which are addicted to timber for revenues) spend almost twice as much per capita as counties with populations greater than 250,000 (there are five in Oregon) to provide services to their residents (see Table 2). Fewer, more populous counties would result in more efficient use of tax dollars. I’m not saying that counties don’t matter but that it does matter if the county is too small (or too large) to be an effective governmental unit.

I once read (though I don’t recall where) that a county’s size was originally intended to allow citizens to ride via horse to the county seat in no more than a day. Populations have increased (or decreased), economies have changed, and roads have been paved. We also have video conferencing, DocuSign, PDFs, websites, online databases, and the post office and other delivery services, so actual trips to the county courthouse are rarely necessary than in days gone by. It’s time for Oregon’s counties to become more efficient at delivering services to citizens. Those efficiency gains can be realized if the Oregon legislature shrinks the number of Oregon counties to best serve the interests of twenty-first-century Oregonians.

Reconfiguring Oregon for the Twenty-First Century

I’ve not drawn an exhaustive map (even if just in my mind), but here are some suggestions:

Like Miami-Dade in Florida, perhaps there should be Portland-Multnomah in Oregon. Since Portland sprawls into Clackamas and Washington Counties, boundary adjustments are in order.

Curry County, carved out of Coos County in 1855, should be reabsorbed by Coos County by 2025.

Wheeler, Sherman, and Gilliam Counties, all with populations well under 2,000, could benefit from consolidation. Wheeler and Gilliam could merge.

Sherman County could again become part of Wasco County, from whence it came in 1889.

Other possible combinations are Polk and Marion; Clatsop and Tillamook; and Umatilla and Morrow.

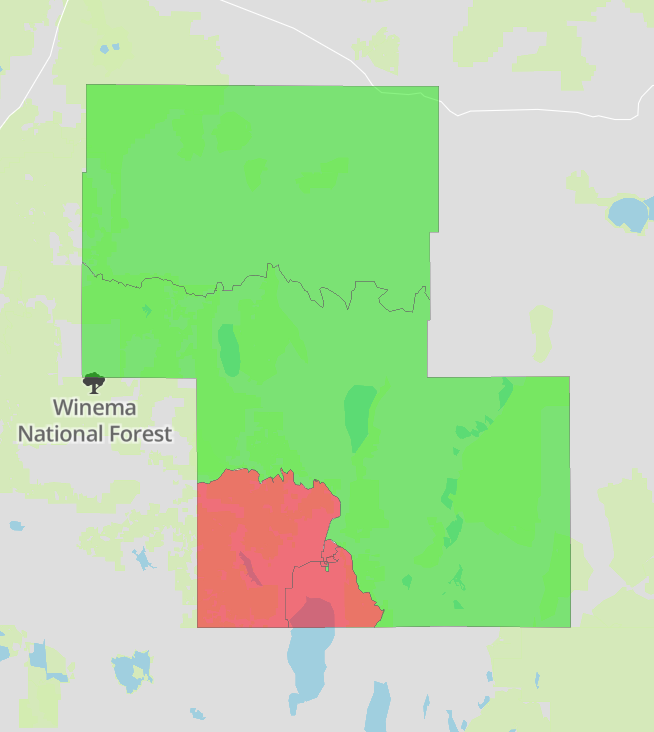

Klamath and Lake Counties could merge to become the Lake County that existed prior to 1882. Northern Lake County should join Deschutes County (Figure 2).

Western Douglas and western Lane Counites could merge with Lincoln County.

County boundaries should be based, when possible, on watershed boundaries. Many boundaries currently approximate watershed divides but are stuck with straight section lines that often cross back and forth.

Renaming Counties for the Twenty-First Century

Beyond resizing, reimaging, and recombining counties, we ought to rebrand them. A few counties are ripe for name changes.

Douglas County was named for Senator Stephen Douglas, who beat Abraham Lincoln to become a senator from Illinois and who Lincoln defeated to become president. Douglas’s career as a politician was one marked by support of a series of compromises to continue to accommodate slavery so as to maintain the Union at any cost. Part of Douglas County was originally Umpqua County. Just a thought.

I’d leave the names of Washington and Lincoln Counties as they are, even though neither is woke enough for some today. (Lewis and Clark are still in use, in the State of Washington.) The former county names of Tuality and Champoeg could come out of retirement and replace Marion, which was named for Francis Marion, a Revolutionary War general for which has been named a national forest and a university in South Carolina.

Consolidating Cities Too

One final note. Lest one think I’m just picking on rural counties, I would suggest that while they’re at it, the Legislature should also encourage the consolidation of adjacent cities, including Coos Bay and North Bend; Burns and Hines; Gresham, Wood Village, and Troutdale; Oregon City, Gladstone, and West Linn; Portland and Milwaukie; King City and Tigard; and Eugene and Springfield (which already share a fire department). Consider Durham, with a population of 1,880, an area of 0.41 square miles, and a density the equivalent of 4,100 people per square mile. The city is surrounded by Tigard (49,140), Tualatin (26,925), and Lake Oswego (37,105); gets its water from the Tigard Water District; contracts for police services from Tualatin; and disposes of its sewage through a regional consortium. Wouldn’t it just make sense for Durham to be part absorbed into a nearby, real, city?

Sources:

Population Research Center, Portland State University, 2020 Annual Oregon Population Report Tables

State of Oregon, Governor’s Task Force on Federal Forest Payments and County Services, January 2009

Ed Stephan, Evolution of Lane County

US Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Lake County, Oregon: Population Change

Wikipedia, List of counties in Oregon

When much or Oregon splits off from Uber liberal kooks in Portland metro then your theory does not matter.

Provocative, to be sure. And I appreciated the table from that task force I staffed on federal forest payments. That table was developed in response to the question, How much does it cost to be a county? But the flip side of that question involves the tax base and the tax system (mostly property taxes) that can support a bare minimum of county services. With small tax bases outside of their federal forest lands and low tax rates frozen by Measure 50, many of the rural counties you mention cannot afford to be counties without subsidies from elsewhere in the the state, namely the larger and more affluent counties. Even growth, in the form of more in-migration and residential development, will not pay for itself at those tax rates -- instead, those dynamics create more demand for services on top of a tax-constrained system. So, yeah, there's a case to be made. But probably not a politically winnable one. The populations of those counties you've held up as possible candidates for mergers will fiercely defend their tax rates as well as their independence. In every case, a lower tax county will be joining a higher tax county, even if they are both have relatively low tax rates. Also, every one of their elected officials, county commissioners and DAs most particularly, will defend not only their jobs but the power they have in one-county-one-vote organizations, like the Association of Oregon Counties and the DAs association, in influencing statewide policy.