Problem Solving the Future for Oregon’s Salmon

Representative Simpson’s (ID-02) provocative “salmon and energy” infrastructure proposal demands serious engagement from all Oregonians, and from the Pacific Northwest congressional delegation.

Editor’s Note: Do your part to Sustain the Way! We’re nearly at $500 raised.

Donate here or subscribe below to create a part-time editor position. Thank you! - kevin

Christina deVillier is a writer, a gardener, and a fourth-generation explorer of northeast Oregon's mountains, canyons, and communities.

Problem Solving the Future for Oregon’s Salmon

U.S. Representative Mike Simpson’s (ID-02) provocative “salmon and energy” infrastructure proposal demands serious engagement from all Oregonians, and from the Pacific Northwest congressional delegation, ASAP. Our region’s future is on the table—in more ways than one.

No matter where you look these days, salmon are having a rough time. Snake River salmon have it harder than most. The wild fish who make it through eight dams (twice) to spawn in Snake River tributaries in my home watershed, in the Wallowa country of northeastern Oregon, are dealing with toxic and acidified oceans, pollution, pesticides, fatally warm water in parts of their migration corridor, degraded spawning habitat, competition from predators and their own hatchery cousins, and the indifference of an economic system that often puts profit before the integrity, much less the abundance, of lands and waters.

All Snake River salmon are listed in the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and despite $17 billion spent over the last decade to keep them from extinction, some biologists believe that if we continue with business as usual, these fish—which once filled our streams so abundantly that Nez Perce people ate 300 pounds of salmon per person per year, and trappers complained about spawning fish swamping their canoes—have got “maybe'' two decades left until extinction.

Today’s low numbers are already devastating for Tribes, outfitters, sportsmen, and hundreds of species of animals (and plants) up and down the food chain in every perennial stream in the interior Pacific Northwest, as well as for ocean animals like the iconic Southern Resident orcas, who rely on Snake River Chinook.

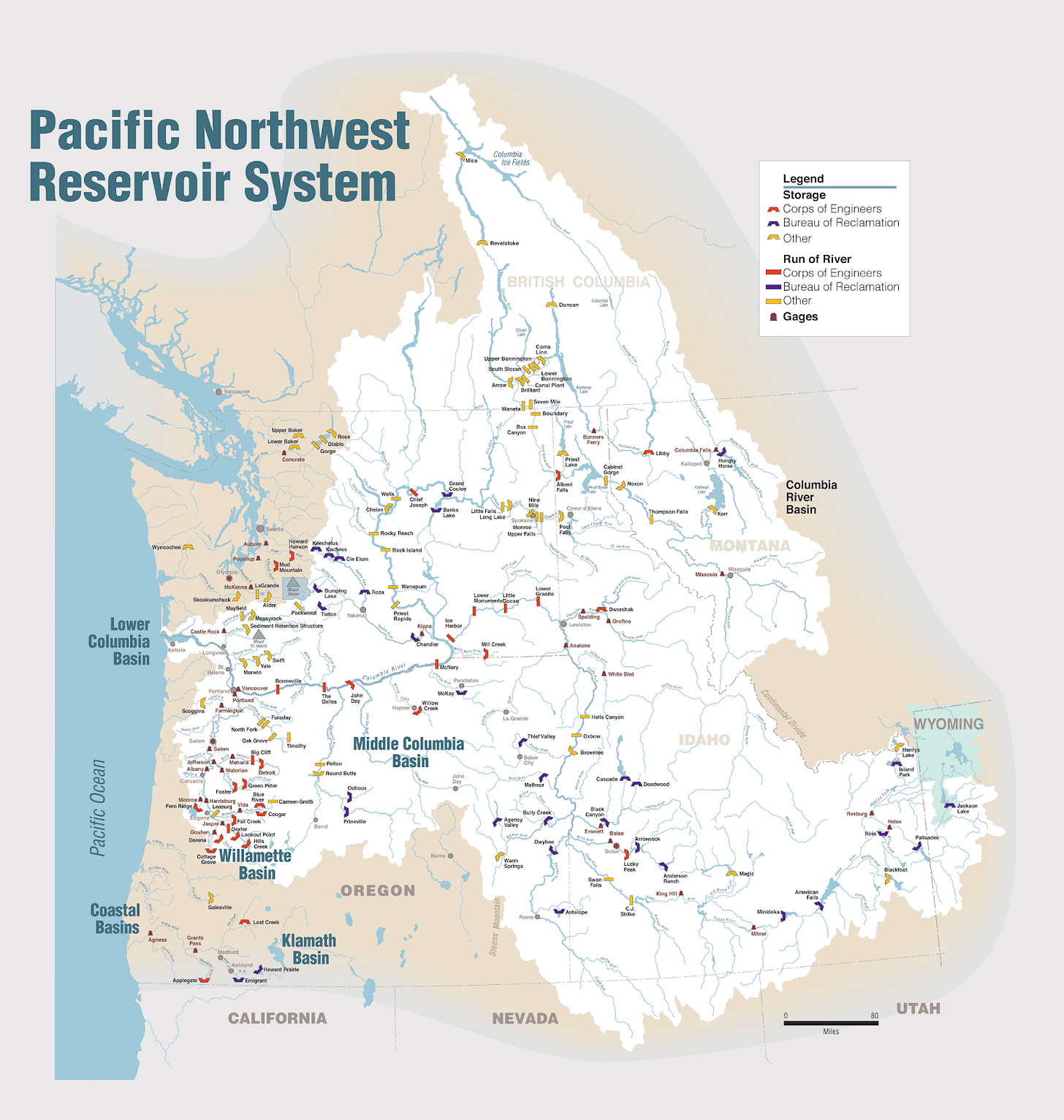

In any death by a thousand cuts, some cuts are deeper than others. Decades of fisheries science have made abundantly clear that eight dams (four on the mainstem Columbia and four more on the Snake) are four too many for Snake River salmon.

Rural communities in the Snake River basin are having a rough time, too. Our small-town struggles reflect a nationwide geographical prosperity gap that has been widening since the 80s.

Employment and wages are stagnant in rural places. Our young people leave, chasing jobs, chipping away at the tax base. Farmers and ranchers struggle with property taxes, succession planning, development pressures, and the rising costs of irrigating and shipping their crops and livestock; these challenges leave working lands vulnerable to fragmentation and mismanagement.

Columbia Basin Tribes, who’ve been hit especially hard by COVID-19, are losing their knowledge-keepers while fighting and innovating to respond to climate impacts on their homelands and lifeways. Staff of state and federal agencies once comprised a strong corps of natural resource management experts in rural places, but staffing at regional offices has contracted dramatically in recent decades; my colleagues and neighbors who once relied on the knowledge and support of OSU extension agents and Forest Service scientists have called this shrinkage a “hollowing out.”

Meanwhile, in places like my home that are blessed with natural beauty, outdoor recreation and tourism have become the major economic drivers, bringing some relief from widespread rural economic decline, and also a whole new suite of challenges.

Over and around all of this, the climate crisis continues to intensify. And the energy landscape is changing rapidly in response. The world’s economies are seeing the writing on the wall and shifting away from fossil carbon, slowly in some places and much more quickly in others. New technologies mean that our energy grids can be retooled for more stability and efficiency than ever before.

In the Pacific Northwest, we’ve historically gotten much of our power from big hydro and coal. The increasing affordability and desirability of greener energy options, along with advances in grid optimization and efficiency, could dramatically change that picture. The power from the big dams that extract the life and liveliness from our rivers is no longer competitive on the wholesale market. Coal plants are closing all over the Northwest and the world. But there’s a lot of inertia in our energy system, so investment in the green(er) transition has lagged behind innovation, especially in rural places.

Let’s keep all of this context in mind as we move into a discussion of a proposal for the Northwest’s future that no Oregonian can afford to ignore.

On February 6th, 2021, U.S. Representative Mike Simpson, a Republican from a conservative district in Idaho, unveiled a bold and provocative proposal that has been years in the making. More than 300 meetings and countless hours of mapping, synthesizing, and problem-solving have produced a big-picture framework designed to address all of these problems at once.

At the center of the proposal is the breaching of the four dams on the lower Snake River, and big investments to replace or retool the irrigation, transportation, and energy benefits those dams provide—to the tune of $33 billion.

There’s something in Simpson’s proposal for every sector in the region. There are billions for voluntary watershed restoration, billions to revitalize interior Northwest economies and reimagine transportation and modernize irrigation, and billions for new power generation to replace the ~4% of the region’s electricity currently supplied by the lower Snake River dams.

Simpson also suggests some interesting restructuring. For example, Bonneville Power Administration would no longer be responsible for managing salmon recovery in the Columbia River basin. Instead, the agency would contribute no more than $600 million per year to a pool of funds for salmon recovery which would be co-managed by States and Tribes. This on its own is a big move for more equity and flexibility in fish recovery work in the basin.

And there’s something in the proposal for everyone to hate. Some folks are just never going to budge in their insistence that the lower Snake River dams are essential infrastructure. And, while many environmental groups, including the one I work for, are excited about the invitation Simpson has extended, most of them, including the one I work for, are not at all keen on certain components of his proposal: most notably, a 35-year litigation moratorium for Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act violations throughout the Columbia River Basin, and an automatic 50-year extension on licences for other dams. Seventeen environmental groups recently issued a strongly worded letter opposing Simpson’s framework, pointing out (rightly, I think) that it is not fair or acceptable to sacrifice bedrock environmental laws throughout the Columbia River basin, or set back salmon recovery elsewhere, for the sake of Snake River fish.

As for me, I grew up in northeast Oregon, and I expect to live here for the rest of my life and raise a family here. So the salmon that return to Northeast Oregon’s 1000+ miles of Snake River tributaries are particularly near and dear to my heart. And these fish, and the ecosystems that depend on them, are in urgent trouble.

And, as a conservation practitioner who’s been working hard for a lot of months to prepare the ground for Simpson’s proposal in Northeast Oregon, since before we knew all the details, I also have talked with many, many of my neighbors about how their real interests—their diets and pastimes, their business models and bottom lines, their sunk costs, their years of compromises and collaborations and learnings, their dreams for their kids—are represented in Simpson’s broad proposal.

And they are. From grid resilience and distributed energy generation, to Tribal Treaty rights and lifeways, to the fate of our local Sockeye reintroduction program, to the futures of the outfitters and guides who’ve helped to revive our rural economies, to irrigation modernization and instream flow leases, to more opportunities for riparian restoration on working lands, with all the co-benefits such work entails—Simpson’s proposal, if it turns into legislation, could bring real benefits to my rural community, while building on decades of collaboration here between irrigators, Tribes, conservation interests, and other land stewards on behalf of fish and fisheries.

And—salmon need clean, cold water, too. And so do our kids and wildlife. And climate change is barreling forward too unpredictably and too quickly to justify automatically extending fifty years of grace to all of the other outdated, river-warming infrastructure in the region. And while ending the cycle of litigation and delay is all well and good, the only reason we’re having this conversation at all is because, for decades, litigants on the Snake, like the Nez Perce Tribe and the State of Oregon and Earthjustice, have never, never, never given up on these fish.

Now, I’m observing folks in my various interlocking communities girding up for battle over Simpson’s proposal—prematurely, in my opinion, though it’s true that things are moving fast.

Look: Simpson’s proposal is not (yet) a bill. It’s an invitation to his colleagues in the Pacific Northwest delegation to work together on a bill. It’s an opening bid on a bill, and it’s a big one. This is the most significant move we’ve ever seen to secure a future for salmon in the interior Pacific Northwest, while also securing some stability, and dare I say some wins, for others in the region whose interests, like or not, are wrapped up with the struggles of Snake River fish.

My most essential point here is that nothing, nothing in Simpson’s proposal is set in stone—yet. What we have here is a wide-open door, a detailed, comprehensive starting point for a solution for these fish that also boldly tackles our region’s energy and rural agricultural futures. Now is the time to lean in and negotiate—not to close the door.

Simpson hopes to enfold his proposal into the $3 trillion infrastructure package the Biden administration is working on. What is needed to make that happen is the partnership—and the pushback—of others in the powerful pacific Northwest delegation: in Oregon, Senators Wyden and/or Merkely and/or Representative DeFazio; in Washington, Senators Cantwell and/or Murray; and so on.

This thing’s moving, one way or the other, and these players are the decision makers who have the power, if they engage, soon, to secure the benefits in Simpson’s proposal, add their own big vision (and ours) for the future of the Pacific Northwest, and mitigate the poison pills.

The timeline is short. That big federal infrastructure proposal could come as soon as May. The tightness of this timeline might seem scary, but the fish, and their attendant cultures and ecologies and economies, simply cannot afford more decades of talk and inaction.

There will be compromises. For sure. And some of them might be very hard to swallow. Personally, I think of this as an exercise in the kind of big, hard, complex, collaborative and costly problem solving we will need to do to address the other huge challenges of our time, like climate change.

If this isn’t the Oregon Way, I don’t know what is. It is big. Be brave. Be discerning, critical, maybe even hopeful. Engage.

If you want to see a future for Snake River salmon, engage. Call or write our Oregon Senators and ask them to get involved with this proposal—to sit at the table that’s being laid and make this thing happen and make it better, ASAP.

If you have specific ideas for how to make it better, share them. Read Simpson’s whole framework. If you have interests (or anxieties) that overlap with one or more of its issue areas—and, if you’re an Oregonian, I bet you do—claim them, and ask for our delegation’s representation to secure (or mitigate) them. Get thee to the media or to social media and claim your interest and tag our Senators and ask them to engage to turn this proposal into an infrastructure bill the Northwest can be proud of.

If you are appalled by the possibility of a 35-year exemption from litigation from Clean Water Act violations, engage. Call your Oregon Senators and Governor Brown and ask them to get to work to negotiate that number downward or away.

If you want problem solving to happen now for the energy grid we want fifty years from now, a grid that’s more resilient to climate-driven disasters and whose benefits are more equitably distributed, engage.

If you respect the right of Tribes in the region to harvest fish at all usual and accustomed places, or if you yourself are a Tribal member for whom salmon declines have been an intergenerational tragedy, engage.

Draw your lines in the sand, and engage. Ask for what you want, and engage. The way forward is hard, and complex, and together.

******************************

Keep the conversation going:

Facebook (facebook.com/oreghttps://theoregonway.substack.com/p/a7baa088-9726-4a94-a153-8cade0f60db6onway)

Twitter (@the_oregon_way)

Check out our podcast: