Reforming our elections: Oregon registers, but does not empower all voters

Under the status quo, candidates will have an ever decreasing need to consider the interests of younger voters. This will weaken our representative system.

Editor’s Note: Do your part to Sustain the Way - donate here or subscribe below to create a part-time editor position. Thank you!

John Horvick: DHM Research, Political Director.

Oregon’s primary elections system is broken. And Motor Voter is making it worse.

Before going further, I want to be clear: I support Motor Voter, and the automatic voter registration process it created. In fact, I believe that all states should adopt automatic voter registration. It is an unambiguous good when more people participate in our democracy.

Yet, it is because I believe in the importance of meaningful participation that I have concluded that the combination of how Oregon manages Motor Voter and how the state operates its closed primary election system is causing harm and must be reformed.

History of Voter Registration

Oregon has closed partisan primary elections. This means that to vote in either the Democratic or Republican primaries a voter must be registered with one of those two parties. Only registered Democrats can vote in Democratic primaries, and just registered Republicans can vote in Republican primaries. Neither can vote in the other’s primaries, and voters who are registered with third parties or are non-affiliated cannot vote in any primary. This categorical and exclusionary approach to primaries applies to elections for president, US Senate, US House of Representatives, Oregon Senate, Oregon House of Representatives, governor, secretary of state, attorney general, and treasurer.

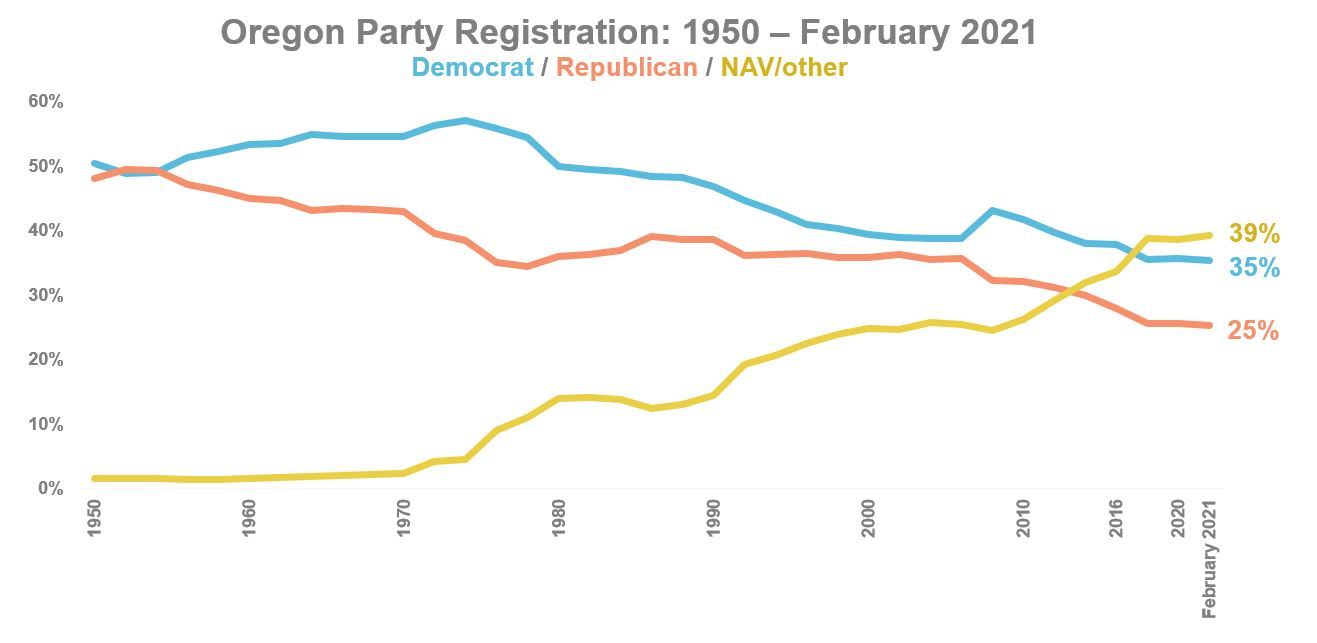

Perhaps this closed approach made sense when the vast majority of voters were registered as either Democrats or Republicans. But as the chart above shows, starting in the 1970s an increasing share of voters were registering with a third party or as non-affiliated. By 1980, 14% of voters were registered as non-affiliated or with third parties, which increased to 25% by 2000 and 29% by 2014.

I start with a look back over the last fifty years and stop at 2014 because it is important to acknowledge that there was significant growth of third party and non-affiliated voters prior to the introduction of Motor Voter. However, Motor Voter, by virtue of its design, has accelerated these trends.

How Motor Voter works

Here is how Motor Voter works. When a person who is eligible to vote interacts with the DMV they are automatically registered. Their default party registration is non-affiliated. Soon, the newly registered voter is mailed a postcard informing them of their status and asking if they would like to register with a political party. If the new voter selects a party and returns the postcard, great, they are a newly minted party registrant. If they choose not to register with a party, that’s fine too, they simply stay registered as a non-affiliated voter.

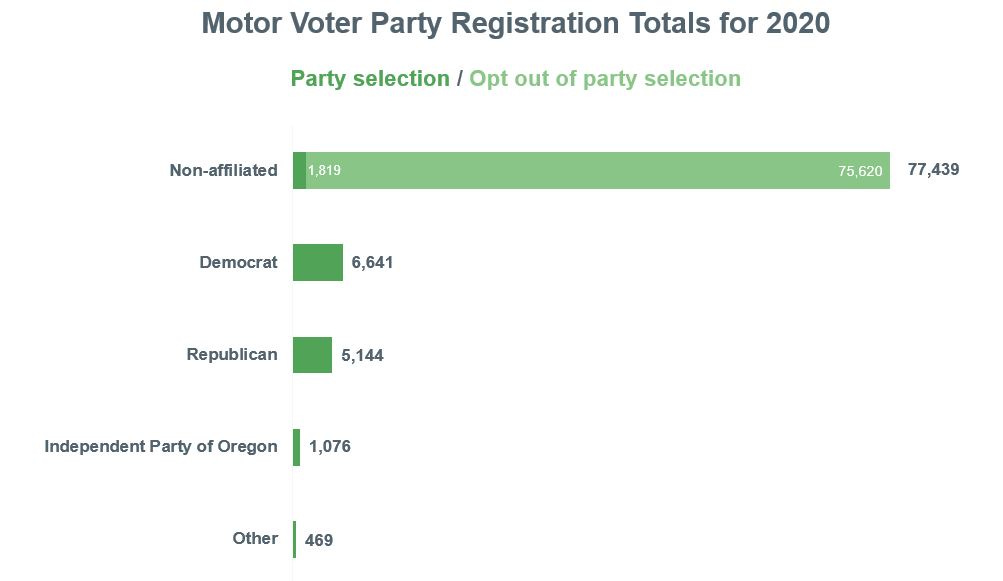

Default choices are powerful and the default assignment of Motor Voter registrants as non-affiliated voters is helping to radically change the electorate as the following two charts show. The first of these shows party choices of Motor Voter registrants for 2020. In 2020, 90,769 Oregonians registered via Motor Voter. Of those, 83% did not select a party and remained non-affiliated (another 2% actively selected non-affiliated).

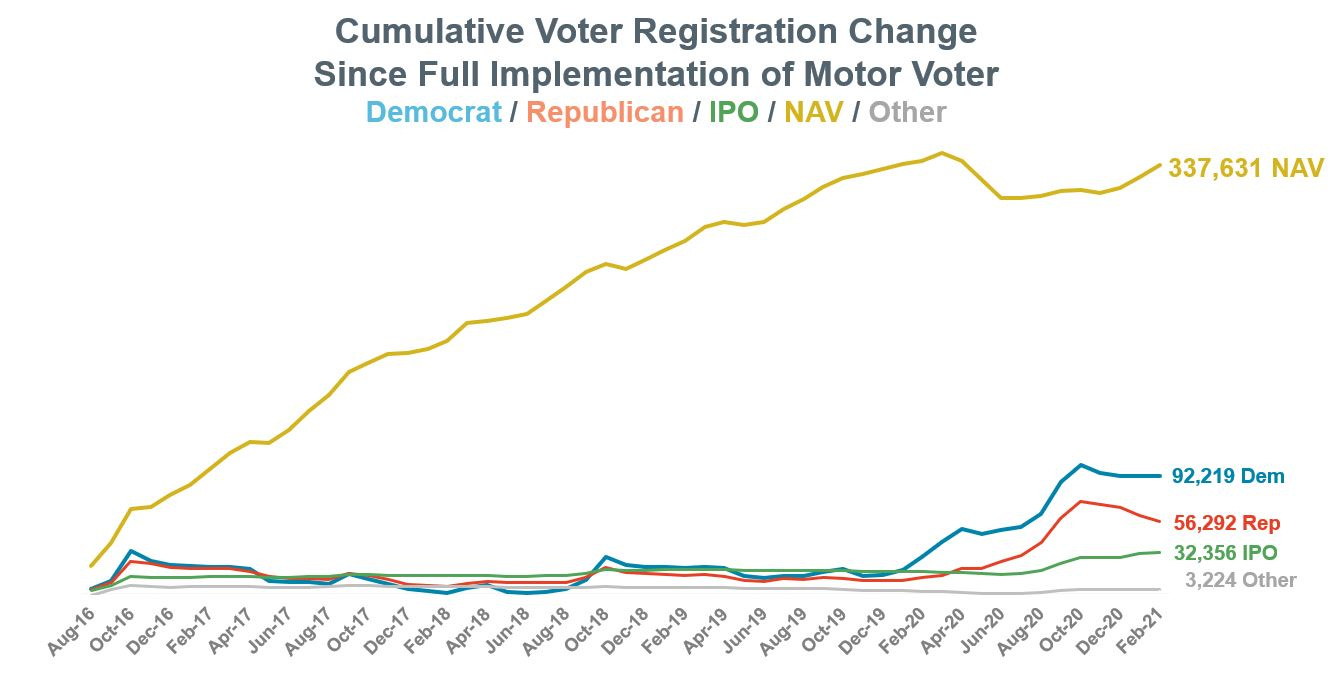

The second shows the cumulative voter registration totals since Oregon fully implemented Motor Voter in 2016. Since then, non-affiliated voters have increased by 337,631, which is more than double the number of Democrats and Republicans combined.

Motor Voter has helped to create an electorate where non-affiliated voters plus third party registrants make up a plurality of voters in Oregon. And soon, non-affiliated voters alone will surpass Democrats to become the largest group of voters.

Importance of primary elections

The closed primary process gives Democrats and Republicans a shortcut to elected office because the winners of those primaries automatically advance to the general election. So, it comes as no surprise that every Oregon federal and statewide elected official is a Democrat or Republican. Similarly unsurprising, 89 of 90 legislators are also Democrats and Republicans, and the one who is not only changed parties after winning his election as a Republican.

In the 2020 general election, there were 76 State House (60) and Senate (16) elections. Of these, 72 were won by the candidate whose party had a registration advantage in the district, a rate of 95%. This means primary elections are highly predictive of the general election winners and, therefore, why it is so crucial to consider who is eligible, or not, to vote in primary elections.

There are currently 958,826 non-affiliated voters in Oregon plus another 201,552 who are registered with third parties, for a total of nearly 1.2 million people who are excluded from our primary elections. These voters matter and should have an equal say in choosing their representatives, rather than being left with a choice between candidates selected by other Oregonians.

Current system excludes young and diverse voters

Including these 1.2 million voters in our primary process is important on its own. For those who say that these non-affiliated or third party voters are lazy for not registering with a “major” party or selfish for not temporarily joining one such party for the sake of the primary are advancing wholly un-Oregonian arguments: placing parties before people. Oregonians have long celebrated lowering barriers to participation, that’s why we passed Motor Voter in the first place. Oregonians have likewise long celebrated open-minded and pragmatic thinking, which does not always fit nicely into a party box.

And because these voters are demographically distinct from registered Democrats and Republicans excluding them from primary elections results in diminishing their interests and mitigating their impact on what occurs in Salem and D.C.

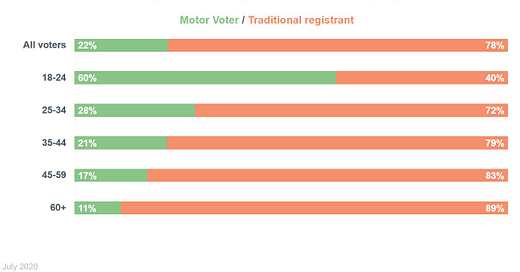

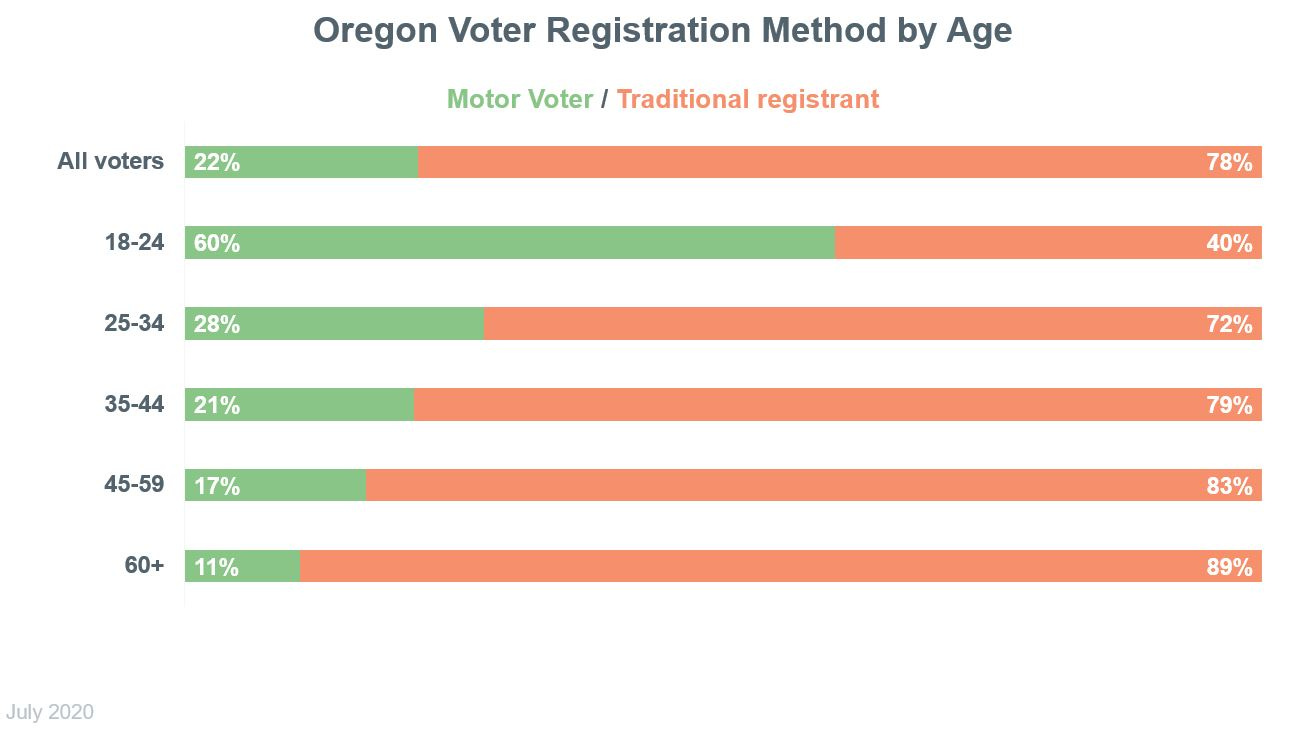

Even prior to Motor Voter younger Oregonians, and younger Americans broadly, had started to move away from the two major parties. Because Motor Voter captures unregistered voters at the DMV, they are also younger than the typical voter. Often they are getting their license for the first time or new to the state. The chart above shows the percentage of voters registered by either Motor Voter or traditional methods by age. These data were pulled in July 2020, and at that time 60% of voters ages 18-24 and 28% of those ages 25-34 were registered via Motor Voter, compared to just 11% of voters ages 65+.

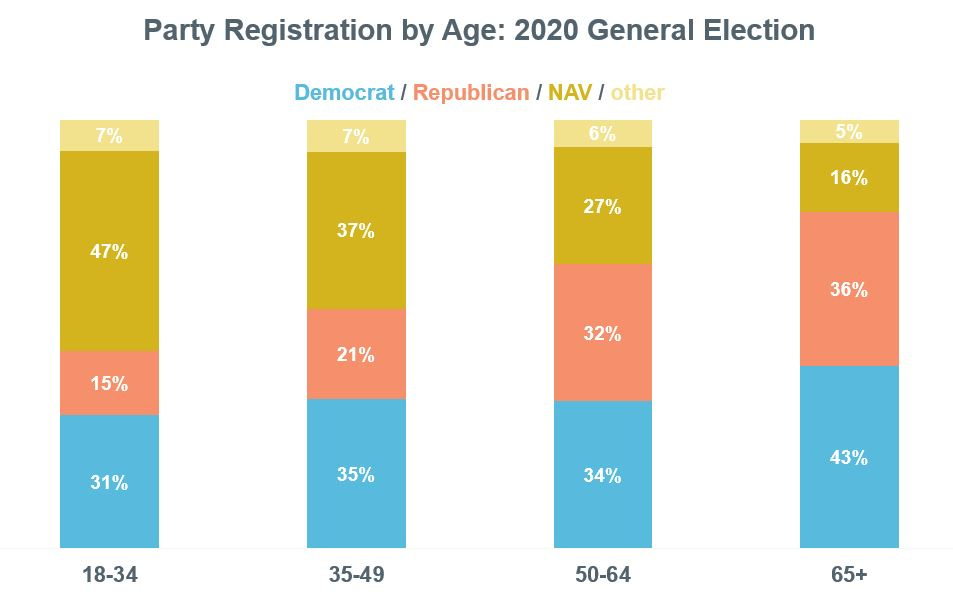

These factors have resulted in wide disparities in party registration by age. This next chart shows registration by age for the 2020 general election.

Nearly half (47%) of voters ages 18-34 were registered as non-affiliated compared to just 16% of those ages 65+. Together with third party registrants, a majority of young voters are not eligible to vote in Oregon’s closed primary elections.

If Oregon continues its system of closed primary elections, and continues to default Motor Voter registrants as non-affiliated, these gaps will increase. As a result, candidates will have an ever decreasing need to consider the interests of younger voters. This will weaken our representative system and fail to deliver benefits that are shared across generations.

Younger voters are also more racially diverse than older generations. The current system, therefore, prioritizes the interests of white voters over voters of color. Both major political parties say that they value the voices of voters of color. If that’s true, they can demonstrate their values by advocating ending closed partisan primaries and ensure that all voters have an equal opportunity to participate in our elections no matter how they were registered.

Reform

There are many potential reforms to the problems outlined here. One is adopting open primaries. Washington and California have top-two open primaries where the two candidates with the most votes in the primary move on to the general election regardless of party. However, in 2008 and 2014 Oregon voters overwhelmingly rejected ballot measures to adopt top-two open primaries. Given this, it probably makes sense to pursue other reforms.

Many states are experimenting with election reforms. Colorado, for example, mails all voters both Republican and Democratic primary ballots and voters can choose either one. Alaska just adopted a top-four open primary followed by ranked choice voting in the general election. There are lots of solutions to choose from. Whatever direction Oregon goes, let’s just make sure that we include all voters.

****************************************

Connect with John:

@horvick

In "The Demobilization of American Voters", publisher Greenwood Press, 1989, author Michael Avey presents information to support his theory that the two parties do not want more voters. The parties do not want young people, people of color, and people earning low wages. He also writes that identifying people's issues and proposing appropriate policies to address and resolve those issues would bring voters into the parties. Too obvious?