Rich Vial: Three is better than one - time for multi-member districts

What is the Oregon Way? Is it not celebration of diverse views? Can we imagine a better way to help support that culture than by creating a system that produces just that in our legislature?

Rich Vial is a former Oregon State Legislator, former Deputy Secretary of State and founder of the law firm Vial-Fotheringham, LLC. He provided legal assistance to hundreds of Homeowner Associations throughout the West for four decades and has always had a passion for how communities organize and govern effectively.

Recently we have heard many calls for greater communication in working toward greater peace and less discord in our communities and our country. From Senator Tim Scott and Congressman Trey Gowdy in their book “Unified, How Our Unlikely Friendship Gives Us Hope For Our Divided Country” to our own Kevin Frazier here on this very blog, there’s a growing recognition that despite differences, if we resolve to talk with and listen to one another, then we can find common ground. I could not agree more.

It’s not covered in the news, nor discussed in the opinion pages, but at the neighbor level—whether that neighbor is on the other side of the condo wall, across the farm fence, or even across the political aisle in our legislative halls—people are talking to one another.

And, when they do so, they inevitably learn that they have more in common than they have differences. In fact, we are so much alike, our choice of ideologic identity is marked by narrow, often very nuanced positions that many of us find confusing. Sadly, though, our politics and media focus on those issues most likely to divide us and so we default to our tribe and, in many cases, blindly accept whatever its stance is on the dividing issue in question.

Leadership of our political tribes has been unequivocally coopted by the two parties who control every aspect of our political and governance reality. These organizations exist to acquire power. Their sole purpose is to gain control of the governance of our nation and our communities. Their business model is to exploit rancor and dissension, and they are assisted by a press that sells conflict for clicks.

We are told that we need to know whether someone has an R or a D after their name in order to know what to expect of that person. And our leaders, ensconced in their party caucuses, reinforce the division by the very system that we all wish was less divisive. We can change our leaders and we can expand our tribes; in other words, we can change the system.

A change that deserves more attention

While a comprehensive overhaul of our system of electing representatives and the rules for their deliberations are the only real solutions to the problem of destructive tribalism, in this essay I wish to address one element of the system that has been consistently named as a source of our political angst: gerrymandering, or the process of parties in power manipulating the development of representative districts to ensure particular party outcomes.

Both parties are guilty of specifically drawing district lines so as to take or maintain control of legislative bodies. Every ten years, on the heels of the national census, this activity becomes the most cantankerous of all legislative activities. Put your seat belt on, because although we have many very difficult issues to address in 2021, redistricting is on the agenda and will be a tumultuous activity.

Addressing the problem of gerrymandering is not a new concept. In Oregon, where the legislature is tasked with coming up with the districts, the two major parties have openly promoted to their base constituencies the importance of maintaining their power in order to control the process.

If the legislature cannot agree (i.e., get consensus of the majority), then it falls to the Secretary of State to draw the lines, at least that’s how Oregon has it set up. The importance of this potential role for the Secretary explains why party officials place such a premium on getting their candidate elected to that office (especially this time around, given that Oregon is expected to add a new congressional district due to population growth).

Though Oregon has some unique quirks when it comes to redistricting, some things are standardized across the country. Like all states, Oregon must comply with constitutional equal population requirements. By statute, its congressional and state legislative districts must be of equal population, “as nearly as practicable.” Oregon must also, like all states, abide by the Voting Rights Act and constitutional rules regarding race. Oregon statutes also provide that no district shall be drawn for the purpose of diluting the voting strength of any language or ethnic minority group.

Additionally, Oregon, like many states, is a “nested” district state, in which each Senate district contains two Representative districts. Oregon statutes establish additional criteria for both state legislative and congressional districts: as nearly as practicable, districts must be contiguous, utilize existing geographic or political boundaries, not divide communities of common interest, and be connected by transportation links. The law also declares that districts will not be drawn for the purpose of favoring a political party, incumbent, or other person. Importantly, the legislature may modify these statutes at any time. [1]

A 2020 ballot initiative to replace this process with an “independent commission” survived litigation, but not COVID-19; it failed to get enough signatures during the pandemic to qualify for the 2020 ballot. [2]

In spite of the law, and efforts to avoid drawing the districts so as to favor a party, the process of redistricting is always the most contentious and partisan activity the legislature engages in. Even in those states where an independent commission or other attempt to avoid the party influence has been instituted, courts have nearly always been the final arbiter, often accused thereafter of being partisan themselves.

Why it’s time to return to multi-member districts

Regardless of who does it, or how it is done, redistricting that retains the single representative district system is not going to help people feel that they are truly represented. Even in those districts with a massive party majority of either color, a large portion of the voters will conclude that they have no one in power who shares their interests. And, as it stands today, they will be right. This feeling of powerlessness diminishes the legitimacy of our system and engenders greater animosity among neighbors. It doesn’t have to be this way…in fact, it didn’t use to be!

In the early days of our democracy, multi-representative districts were the rule. Gradually, however, a desire to have Congress made up of people who were close to their constituents led to breaking up the districts into smaller, single representative districts. Even though it is not a constitutional requirement, or even a congressional mandate, virtually every state now elects representatives to Congress by a single district. Ironically, many states, including Oregon, don’t even require the representative to live in the district, but smugly assume that with only 600,000 or so constituents, a representative can truly know the ideologies and desires of the people in their district.

Let’s admit that we live next to folks who would vote for a different candidate than we would (just read Jim Moore’s November piece for proof). That doesn’t mean that we can’t get along, but it recognizes the fact that we all have different ideologies and priorities. And, no matter how hard we try to lump them into blue and red, conservative and liberal, capitalist and socialist, or any of the other labels we use, our differences are much more complex and nuanced. Allowing a party to define our representative, and choosing only one for a group of people with a wide range of interests and desires is ludicrous.

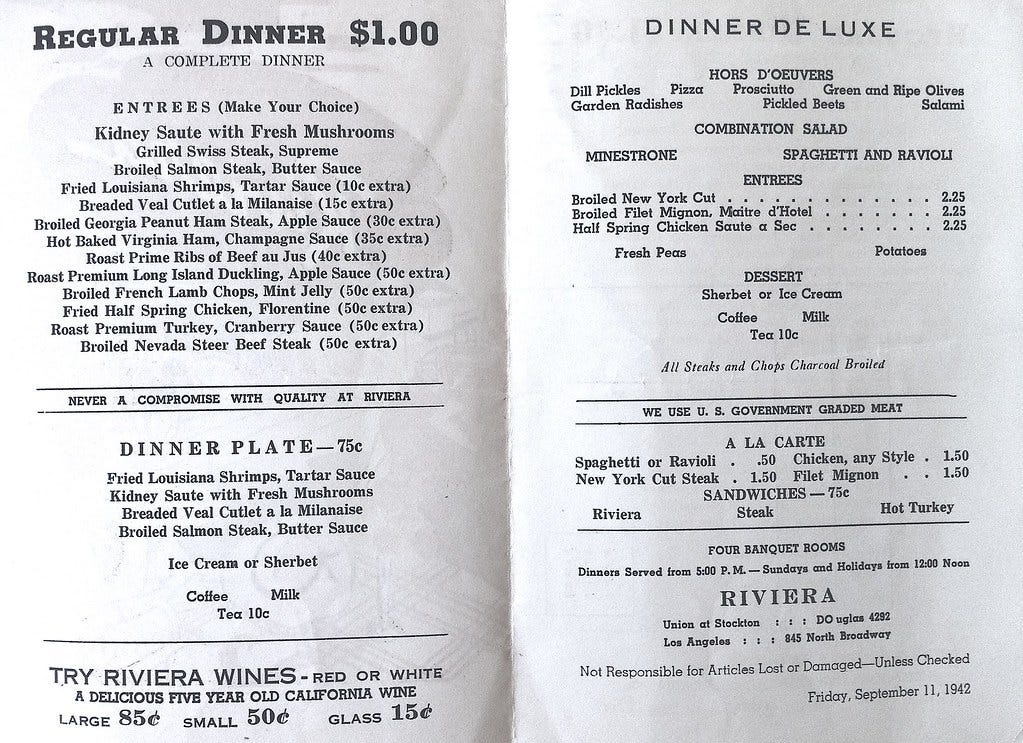

Imagine going to a restaurant with a group of ten friends—in a single district restaurant, you have no option other than to eat what a majority of your friends wants for the appetizer, main course, and dessert.

In a multi-member district, two of your friends may get to decide on the appetizer, another two on the dessert, and the remaining four, the largest bunch, will determine the main course. It’s not hard to see which meal would leave more people feeling satisfied. How to realize this outcome in an electoral context will be covered next.

In Oregon, we have a very easy solution. Make all offices in Oregon non-partisan from Governor down to State Representatives. A couple of words in our statutes could accomplish this. Once done, it would then be very easy to consolidate our Representative and Senate Districts and elect three representatives each from our existing 30 Senate districts. In other words, a single election would take place for the entire Senate district – the top voter getter would serve as that district’s Senator, the next two vote getters would serve as the Representatives.

This approach creates a new way for minorities in communities to receive the representation they deserve. Those who are in the minority whether in North Portland or remote Eastern Oregon suddenly have the opportunity to band together to elect one of the multiple representatives. Everyone has someone who is closer to sharing their views that is from their district.

The way to run this election is easy. First, open the primaries to anyone who is able to gather signatures of at least 500 voters from their district. Next, move the top five vote getters in the primary to the general election. Third, using Ranked Choice Voting, send the first place winner to the Senate, with the 2nd and 3rd place candidates going to the House.

Policy and party identity will still factor into this approach to elections. After all, every voter and every candidate has ideological preferences and those preferences matter. What shouldn’t matter is which party had control of the State legislature during the last redistricting process—but right now, that fact is often determinative – your district was drawn to be blue or red. Non-partisan primaries and RCV election of multiple representatives is likely to give us a much more balanced cast of representatives, and an increased likelihood that each of us will have at least one person in our legislative halls with whom we can speak, confident that they will understand our thoughts and desires.

What is the Oregon Way? Is it not celebration of diverse views? Can we imagine a better way to help support that culture than by creating a system that produces just that in our legislative halls?

*******************************************

[1] [Or. Const. art. IV, § 7; Or. Rev. Stat. § 188.010]

[2] [People Not Politicians Oregon v. Clarno, No. 20-35630 (9th Cir. Sept. 1, 2020); Fletchall v. Rosenblum, No. S066460 (Ore. S. Ct. Sept. 4, 2019); Fletchall v. Rosenblum, 448 P.3d 634 (Ore. 2019); Fletchall v. Rosenblum, 442 P.3d 193 (Ore. 2019)]

*******************************************

Send feedback to Rich:

arv@vf-law.com

Keep the conversation going:

Facebook (facebook.com/oregonway)

Twitter (@the_oregon_way)

Check out our podcast: