RtOW: Chapter 2 - The Chattanooga Way

Oregon isn't the only place that's benefited from an atmosphere of collaboration.

*Editor’s Note* For the next several Saturdays, I will be posting an excerpt from my book, “Rediscovering the Oregon Way.” This effort started two years ago in the middle of my current role as a graduate school student. I spent weekend mornings doing research, late nights conducting interviews, and spare moments looking for typos.

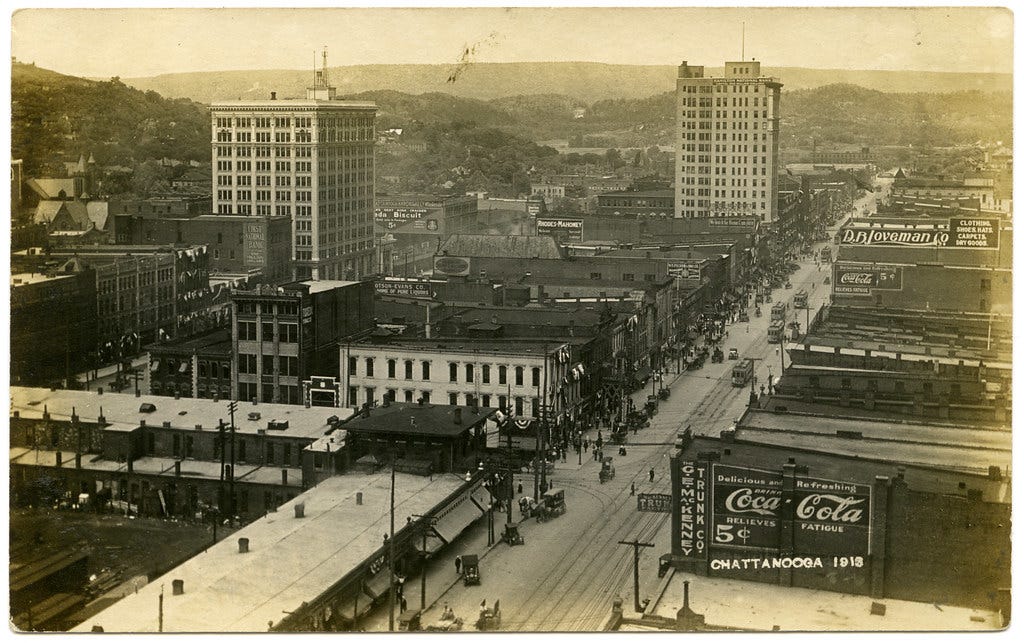

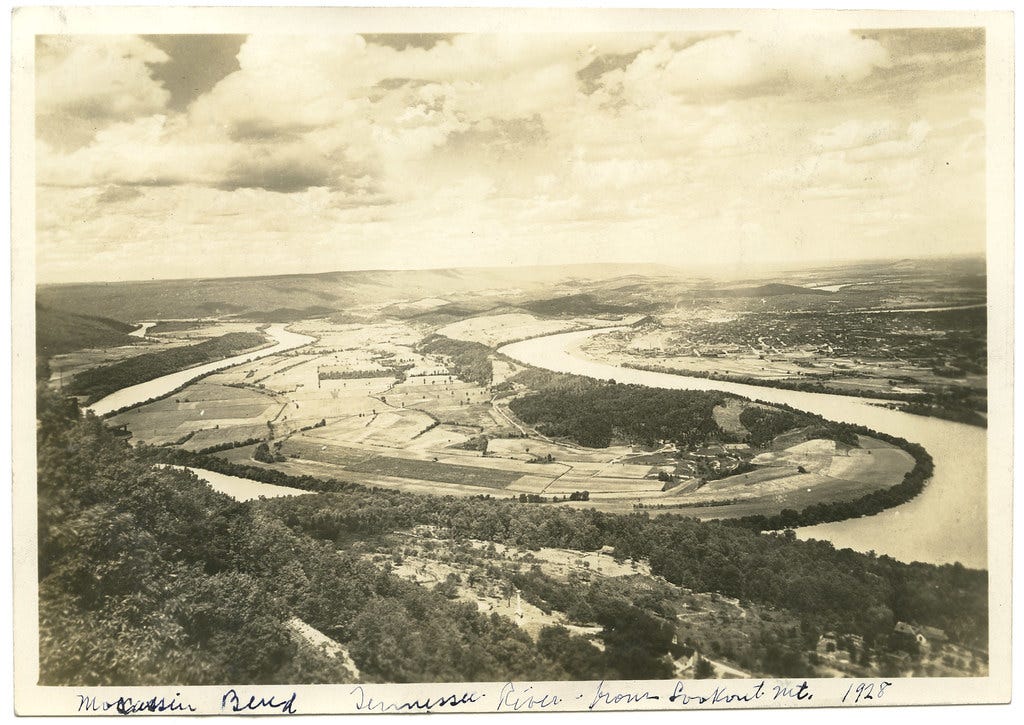

A younger, more diverse Way has taken root in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Its formation reveals that Ways can come about quickly or slowly, so long as shared values, enforced norms, strong social institutions, and participatory democratic processes exist. According to Mayor Andy Berke, first elected to the role in 2013, the city’s Way developed around a pivotal decision: how to orient the area’s growth and development over the next several decades. In 1986, the City identified its portion of the Tennessee River as the epicenter of economic and cultural revival; they mapped out a 20-year, twenty-two mile vision for the riverfront and downtown area. A look back at how the City reached that directive reveals the formation of a Way that continues today.

This Way developed because of, not in spite of, racial and class divisions, the same divisions that people cite today as insurmountable barriers to unified action. Chattanooga's approach to these assumed barriers exposes that diversity can become a shared, unifying value that reinforces the other elements of a Way. For those wondering, Hawaii’s Way initially came out because of blatant recognition of race as well. As recounted by sociologist Moon-Kie Jung, Hawaiians responded to the demographic and economic changes brought to the archipelago by World War II by making a conscious choice to see race and to create a space at various decision making tables for representatives of several races. By way of example, according to Jung, race was the rationale to get a diverse group of labor organizers together for a larger conversation about economic justice. Once at the table, though, race faded to the background as mutual values and norms emerged. This sort of "proto affirmative action" signaled that every race had an equal right to membership within a more expansive in-group. Chattanooga’s opportunity to re-examine racial relations also came from a tumultuous period that spurred the need to prioritize a unified rather than fractured response.

A 1980 report by a noted urbanist, Gianni Longo, evidenced that hopelessness filled Chattanooga; residents, especially poor and minority residents, felt they had no voice nor future in the city. The deterioration of Chattanooga’s civic spirit was paired with physical disrepair: the city was declared the most polluted city in 1969. What laid in front of the City, per Longo, was a reknitting process. The social fabric was torn apart and required some thorough mending (as did the environment). So the City decided to actively seek out the voices and visions for the future of residents that felt disconnected and disrespected.

The visioning effort at the time was referred to as Chattanooga Venture, it launched with an extensive surveying initiative. Volunteers with Venture talked with 500 residents and solicited their feedback on what defined the city, what made it great, where it could improve, and what actions the City government should prioritize. This visioning effort, a wonderful expression of an open democratic process, sparked informal and formal activities that established new norms, identified common values, and empowered social institutions. But based on the origins of the Venture, you’d never expect it to have led to such a meaningful transformation of the city and the creation of a Way.

Perhaps determined to reverse at least some of the hopelessness outlined by Longo, several Chattanoogans held informal meetings around how to improve their city. This initial, small visioning effort resulted in a concert series, called the Five Nights, that was held in the early 1980s. Hosted in the middle of downtown, it challenged the previously accepted norm that downtown was not a desirable nor safe space for anyone to go after the sun went down. Headliners such as B.B. King, though, motivated residents of all ages and backgrounds to buck that notion. Chattanoogans turned out in droves to hear King play. But they didn’t just come out on a single night, crowds packed each night of the concert series.

The robust concert attendance demonstrated that it was normal to peacefully convene, even in the center of the city. Social institutions took note of the change and helped perpetuate its positive outcomes. Chattanooga’s institutions, such as the University of Tennessee and the Urban Land Institute, were spurred to action by the upheaval of assumptions about the city’s political culture. Their actions aligned with the role assigned to social institutions in a Way: identifying specific values and norms, expressing these new values and norms in an accessible manner, and then accelerating adherence to these new cultural patterns.

Chattanooga’s Way may have never started absent its social institution; the concert would have been nothing more than a musical anomaly. With social institutions, the energy of the concert was sustained and funneled into similarly transformative and communal activities. For starters, leading social institutions developed a citizen-led task force charged with making citizen-informed policymaking the new standard for the city. This standard, as well as the task force itself, was predicated on advice from Carr, Lynch Associates to the leaders overseeing this bold endeavor: "This thing, [the task force], will only succeed if you reach out to all in the community."

The Moccasin Bend Task Force launched and prioritized the process of gathering community feedback over ensuring particular outcomes. Of the people and for the people, the task force took its mandate to facilitate broad and open participation seriously. Over just three years, the task force planned and hosted 65 public meetings with a particular focus on how to reimagine the Tennessee River. The meetings required every other aspect of a Way to be tapped: public libraries hosted the meetings (social institutions), community members felt compelled to participate (norms), and the meetings stayed focused on being inclusive and action-oriented (values). Democratic processes underlying the nascent Way only worked because the other conditions for a Way were in place.

Unsurprisingly, the process of receiving feedback from as many Chattanoogans as possible brought up some difficult issues and disparate opinions. A common value, however, was at the center of otherwise unconnected fears expressed by many participants. What they feared ranged from environmental degradation to a lack of safety in the downtown area. What they valued, though, was centered on a reverence for Chattanooga as a place. People wanted their land, their heritage, and their artifacts preserved and protected.

The task force recognized this widespread and deeply held value. They identified this value by continually seeking and incorporating feedback from Chattanoogans. With each flood of feedback from meetings and canvassing efforts, a Way began to come into place: expectations around decorum and participation became norms, individual concerns were coalesced into community values, and social institutions helped ensure that results uncovered through democratic processes were actually implemented. By 1983, Chattanooga had already become a case study in the efficacy of people-driven governance that concentrated on considerations of livability and quality of life.

Chattanooga’s success drew the attention of outsiders. Turns out that a successful Way attracts others looking to get stuff done in their own community. Regardless of geography, both corporate interests and the general public are attracted to places where quality of life is a priority and involvement is positively correlated with favorable results. Communities with a Way are more resilient and, thus, better investments whether you want to start a business or a family. The Chattanooga Way eventually caught the attention of the economic development interests within the city and surrounding region.

Some of these stakeholders were less committed to the necessity of adhering to the norms and values associated with the budding Way. They saw the city’s Way as an investment opportunity but did not prioritize becoming a real part of the in-group forged by a love for Chattanooga. Called “the Options Study Group,” this small cadre of Chattanoogans thought they were doing the city a favor by using the Way as a lure to bring new business to town. The Group even went so far as to craft their own economic development, not with the people, but for them.

Thankfully, this effort was stymied and labeled as antithetical to the Way. Adopting the top-down plan authored by the Group threatened the core tenets of the Way which was responsible for the city’s turnaround possible. To escape this fate associated with letting a small group of people shape the economic future of the city, community members adopted a simple strategy: integration. A Coordinating Council, aka a superboard of civic, corporate, and city leaders, joined together. This inclusive and representative body filtered ideas for improving the city through the values of the Way. This approach ensured that any new business would not only be welcomed by a wide-swath of civic society but also conform to the Way’s values and norms.

Soon the Council became a core part of the broader Way and connected with Chattanooga Venture—the primary community outreach mechanism. The combination of these social institutions again served a funneling function. New, outside energy from non-Chattanoogan entities could have threatened the city’s budding Way by changing the complexion of the city’s demographics, industry, and politics. The strength of Venture and the Council prevented this by checking and moderating any forces not aligned with the Way as well as by supporting activities that strengthened the future that Chattanoogans were trying to build. The fact that Venture was “an open association of citizens, a channel for the exchange of information, a means to focus the collective energy of the community and a tool for solving problems and setting a direction for the future” meant that it had broad community support, including from community members that previously shied away from civic engagement.

Untarnished by outside influence and propelled by public support, Venture mapped out a new initiative: Vision 2000. This initiative tapped into people’s passion for participatory processes associated with a Way as well as their hopes to create a better future. Venture organizers again leaned on social institutions, norms, and values to create a process that merited residents’ involvement. Approximately 1,700 residents participated in these visioning conversations. These visions reflected the views and priorities of a wide range of Chattanoogans. Working moms and dads, for instance, could show up to the convening sessions thanks to the provision of child care and transportation by the Lyndhurst Foundation. The broad range of participants did much more than just talk about their vision, the democratic process did not end with merely participants being heard.

Vision participants had the opportunity to implement the 40 prioritized ideas identified from the total 2,500 gathered in the initial outreach phase. Vision 2000 task forces formed. Members included anyone with interest and passion. Social institutions, seeing the community buy-in to these goals, felt comfortable risking capital to make priorities into actual programs. In total, the 40 community goals sparked more than 223 programs, supported by $790 million in investment.

Outsiders to the area sensed that something unique was taking place in Chattanooga. One foundation head cited "a very impressive spirit." Insiders, too, sensed the power of this spirit, but to some, the power conveyed by the community was a threat rather than a cause for celebration. Venture hit headwinds when it appeared to have too much sway over the direction of the city. Suddenly, the folks and stakeholders used to having their opinions dominate the city’s direction felt they had lost influence. As Venture broadened its approach from just gathering input to actually investing large sums of money, the old political guard pushed back on the community-focus at the heart of the Way.

Their pushes propped up a wall that restored the old order of things—visioning priorities were now reviewed by political experts, rather than community stakeholders. The leaders that steered the Vision 2000 initiative off of the Way argued that they had no choice—the stakes were too high, expert analysis was required, deference to political elites would help the city out in the long run. The process no longer mattered . . . political legacies were at stake.

Do you sense a pattern? Everyone supports community-based governance until their own influence is curtailed. Building a culture of engagement that transcends a single issue or episode requires making community-based governance more than just a means to an end.

Chattanooga got external funding for many of its Vision 2000 priorities by touting the involvement of “experts” and the old guard. But in diverting off the Way to receive those funds, political elites threatened the community-wide momentum that the visioning effort had accumulated. Despite this pressure, the Way was not fully lost. A new economic development organization, River City Co., revived the spirit of the Way.

River City Co. activated Chattanoogans eager to put their values into action and strengthen community norms [another instance of a strong social institution sustaining the energy of the people.] From helping finish the Tennessee Riverpark in 1989 through planning the Coolidge Park in 1999, River City Co. had a finger in every pecan pie and relied on the broader community to guide the company’s involvement. Though far from perfectly designed for maximum citizen engagement, River City kept the Way intact, at least partially.

Other social institutions, such as the newly created Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise, likewise sprouted and generated opportunities for norms to be strengthened and values to be exchanged. Venture also persisted in holding up the Way it helped create; they hosted forums, funded community-identified initiatives, and restarted visioning processes. But Venture experienced less success as the political and economic leaders adopted new norms that did not include community involvement. Projects identified by grassroots processes were trimmed and reshaped by officials seeking to "entice" the governor and other potential sources of political and economic capital. For these “leaders” citizen input was just a means to an end. This difference in norms between elites and common Chattanoogans meant their city’s Way was a table with only three legs. Looking at the table from above, you would see no problems. As soon as you put pressure on it though, the flaws would be extremely obvious.

The three-legged Way never fully disappeared in the ensuing decades. Citizens kept it alive. Though leaders shortchanged the long, difficult process involved with keeping a Way updated, citizens seized every opportunity to participate; they even helped start Revision 2000. In doing so, they celebrated a norm that their robust and repeated participation established: "the more voices that converge, the more they [leaders] have to listen." With that norm in place, outcomes of the first generation of the Way carried on: neighborhood associations, which had grown from a total of six to eighty across the city, continued to meet; task forces convened; and, vision-informed initiatives such as Create Here were carried out.

Fast forward to the City’s recent endeavor to become the “Gig City” and you can see the Way has recovered to almost full force. The path back to near full capacity meant leaning heavily on the three strong legs (social institutions, shared values, and open democratic processes) while electing leaders capable of restoring the fourth (norms that aligned throughout the social spectrum). Chattanooga needed leaders humble enough to see public engagement as a feature, not a bug. The modern class of elected officials have moved closer to that level of humility. The mayors of this era—Jon Kinsey (1997-2001), Bob Corker (2001-2005), Ron Littlefield (2005-2013), and Andy Berke (2013-present)—represent three political parties and a variety of backgrounds, yet all share a deep respect for Chattanooga’s communities, culture, and climate.

Each leader was humble enough to sacrifice some of their own mayoral influence to create room for the revival of the Way. Mayor Kinsey introduced a vision for a more self-sufficient city. Others quickly saw the future he envisioned and found opportunities to join the effort. One particular Way-strengthening action was Mayor Kinsey's creation of the Department of Neighborhood Services. This government office gave social institutions such as neighborhood associations more resources and information. This investment in community-based organizations represented a win-win in the eyes of Mayor Kinsey. The government showed itself as a partner to community activists, an action that at once gave activists greater agency over their community and the city more insights into the needs and wants of its residents.

Mayor Corker added another layer to the city's civic foundation. His ChattanoogaRESULTS program made city government more responsive and more transparent in its provision of public services. The program required public services department heads to join a monthly meeting centered on project evaluations and goal making. With the Mayor at the helm, the meetings revealed inefficiencies and areas with limited accountability; the effectiveness of these sessions resulted in the next mayor, Ron Littlefield, continuing them under his administration. Overall, Corker meticulously nurtured a certain atmosphere to City Hall that facilitated agencies and departments working together and actually getting stuff done [sure this likely sounds cliché, but seeing progress is an element of any good government; celebrating civic progress follows the same rationale for celebrating every time you cross something off a to-do list—pointing out small wins can make an avalanche of future positive actions].

If Mayor Corker had a to-do list then one item would surely have been improving education. He succeeded in crossing off that item by launching the Community Education Alliance (CEA). The Alliance aimed to adjust teachers' incentives to promote better learning outcomes. But overhauling the evaluation scheme for teachers as well as principals did not come easily; thankfully, the tenets of the Way presented strategies to get around these barriers. Input from community leaders and guidance from county officials resulted in the Alliance getting off the ground [in the jargon of a Way, a norm of participation among a variety of social institutions made this open democratic process possible]. CEA’s growth started from these processes and norms and persisted based on two shared values: the importance of children and the nobility of the teaching profession. These values served as the Alliance’s North Star. Like bumpers at a bowling alley, the values of the Way guided initiatives from Corker and others on course for a strike. Put differently, the values made sure that the community’s energy and the city’s resources were not improperly allocated. The processes used to cross “improving education” off Corker’s to-do list, made it easier for him to tackle several other items. Before he left the Mayor’s Office for the U.S. Senate, he could tick off several completed projects that made Chattanooga a better place to call home, including building a new saltwater building at the aquarium and expanding the river walk.

Corker leaving swung the office door open to Ron Littlefield, who held onto the city’s reins as mayor for two terms, from 2005 to 2013. Littlefield shared the love for Chattanooga evidenced by his two immediate predecessors. His previous time as the head of Chattanooga Venture equipped him with the humility to share power with the people. This humility was evident as well in how Littlefield performed in a different political office. As the City’s Commissioner of Public Works, he pushed through reforms that changed the city council from a city-wide district to single member districts that brought elected officials closer to a smaller number of constituents (something that proved valuable to the stability of Vermont’s Way).

As Mayor, though, Littlefield had to overcome a loud and motivated faction of voters that opposed his agenda. Despite successive mayoral administrations adding to the foundation of the city’s Way, no Way is entirely immune to discord. A Way at the city level is particularly vulnerable to the tides of state and national politics. Littlefield’s time at the helm of Chattanooga was almost ended in 2010 when the Tea Party tried to recall him. Ultimately, the recall effort did not even make it to the ballot but the Tea Party succeeded in showing that a norm of public engagement can challenge a city’s stability if that engagement is channeled toward extreme values held by a small faction of the community. The restoration of shared values after the polarizing efforts of the Tea Party did not come easily. Mayor Littlefield tried his best to lead the community toward such values as has his successor Andy Berke, Chattanooga’s mayor since 2013. Berke has thus far maintained the Way paved by the previous mayors of the 21st Century and covered some of the potholes created by political animosity.

The city’s Way did not withstand external and internal pressure solely because of support from city hall. At the nadir of the city’s Way in 2010, Chattanooga needed to pursue radical transformation to get back on track. Social institutions such as River City Co. were again relied on to advocate for and spread the norms, values, and processes of the Way. A variety of institutions had several ideas for what transformations could jumpstart the city and tie pieces of the social fabric back together. Elected officials and community leaders, responding to the guidance of said institutions, felt an obligation to conduct themselves according to and to craft their policies within the confines of the Chattanooga Way. Institutional knowledge, then, made it possible for the Way to stick around and for it to guide Chattanooga through its transformation into the Gig City.

In 1996, the Way started to infiltrate more governance conversations thanks to pressure from social institutions and officials’ deference to the Way and its tenet of community engagement. Mayor Kinsey knew that his administration would fare well if it adhered to the community’s expectations. Consequently, every city department and agency felt a push from Mayor Kinsey to adhere to the tenets of the Way, that included the Electric Power Board (EPB). Harold DePriest, CEO of the EPB, responded to pressure from the Mayor and his team by prompting his organization to undergo a massive cultural shift. His staff spent more time in the community and paid more attention to how the EPB could do more than just meet present needs but actually set the city up for long-term success. These outwardly simple steps were expressions of the values and norms generated by the Way. By 2006, the EPB was ready to take bold action—the creation of a citywide fiber optic Internet network that would allow for gigabit-per-second download and upload speeds.

Democratic processes then kicked in and approved of the EPB's path forward. Even with a great plan, the EPB had to communicate its vision to the community and ensure that resident feedback was visibly incorporated into its initiatives. A new visioning initiative took off. Private and public institutions alike joined together to jumpstart yet another conversation with Chattanooga’s communities. As in the past, the initiative started with forming a diverse coalition. Mayor Andy Berke, elected in 2013, specifically mentioned...you guessed it...River City Co. as among the many corporations, civic groups, and nonprofits that turned mere ideas for a better city into productive conversations and, later, faster, more affordable Internet. These institutions made sure community members were aware of the EPB’s plans and integrated into all phases of the development process.

Quoting Ken Hays, Chief of Staff to Mayor Kinsey, Mayor Berke said Chattanooga’s social institutions and public officials realized that “working together works.” The city’s community leaders from the early 80s would surely have agreed with the Mayor. This simple mantra has become a simple formula that residents, social institutions, and officials revere and regularly employ. It has produced wonderful, city-changing outcomes such as the Create Here process that culminated in downtown Chattanooga attracting entrepreneurs and young professionals.

Mayor Berke made clear that Chattanoogans’ continued willingness to participate in civic affairs comes from their expectation that their input will prove influential, as it did in the early 80s and late 90s. Participation without progress, in the Mayor’s mind, is a recipe for subverting the will of people to get civically engaged. That is why the City proactively thinks about what it can do to display the impact of involvement. Berke proudly points out that citizen councils have succeeded in demonstrating the returns on participating in democratic processes. The Mayor regularly tells people about the Mayor’s Council for Women, which meets quarterly and tends to attract upwards of 200 women. From these gatherings, the Council has shaped state-level policy and developed several white papers. Women attend each meeting knowing that they will do more than just fill seats—they will change policy.

A review of the origin of the Chattanooga Way validates that Ways also depend on a bold vision. One pivotal question—where do you want this city to go—gave Chattanooga’s social institutions, politicians, and residents an opportunity to establish a political culture. From that vision came a series of hurdles to carving out an explicit Way. Private, public, and nonprofit stakeholders had to consent to the vision. Leaders of these various sectors then had to create processes that would facilitate participation. Even with participation, though, the city still had to foster a norm of meaningful engagement and power sharing in order to sustain involvement. And, finally, the entire vision and process needed to build on shared values, which is only possible with a diverse range of leaders bringing their constituents’ values to the fore.

The most strident defenders of the Chattanooga Way will tell you that it is not perfect. Folks, including some of the earliest stalwarts of the city's Way, have questioned whether the city's turnaround and development of a Way was "a true, populist reinvention of a post-industrial Southern city or just a public relations campaign strapped to a slick comeback story." Decades into following this Way, Chattanooga has viscerally changed but the people originally left on the margin of the way back in the 1980s are now completely left behind. Research by the Chattanooga Times Free Press extensively documents the divergent outcomes fostered by the Way. From 1999 to 2015, the Way paved new streets and raised new skyscrapers but did not uplift the thousands of Chattanoogans that were poorer, more rent burdened, and less financially stable.

Mayor Berke knows that the Chattanooga Way may never look exactly as it did in the 80s under the care of Venture. Heck, even that 80s rendition of the Way had several faults. But the Mayor makes clear that he still believes the Way has influence over city policy, stakeholder behavior, and community engagement. It may not exist in statute, but the atmosphere of the Way, according to Mayor Berke, persists and still reinforces values and norms that uphold democratic processes and engage social institutions.

Others lament how the Way has transformed since its heyday in the 80s: they complain that contemporary city officials talk about community engagement one day, only to rely on "expert" opinion alone the next; they note that the willingness of officials from the private, public, and nonprofit sectors to share power has ebbed and flowed; and, they question if the Way has become a checklist rather than a culture. These developments have the potential to short circuit the perpetuation of the city’s Way.

When citizen engagement is performative rather than instructive, people eventually catch on and come to place less value on being engaged and informed. Current Chattanoogans are trying to create a new version of Venture to restore the effectiveness of community engagement. The 80s version of Venture was flawed but it gave residents a model to follow and vernacular to employ for the future; it created a story that helped residents see themselves as the good guys, ready to combat threats to their heroine—their city. Even if the story of the Way gets bent and revised every few years, the story still matters for something. It lures people to the city and keeps natives in town based on an expectation—part fact, part myth—that their voice will be heard, their participation is expected, and their leaders will listen and take action.

****************************************************

Send feedback to Kevin:

@kevintfrazier

Keep the conversation going:

Facebook (facebook.com/oregonway), Twitter (@the_oregon_way)

Check out our podcast: