RtOW: Chapter 5 - The Early Oregon Way

The Oregon Way did not realize its potential in the first fifty years of the state’s political history. A narrow definition of “us" undermined the state's ability to govern for all.

*Editor’s Note* For the next several Saturdays, I will be posting an excerpt from my book, “Rediscovering the Oregon Way.” This effort started two years ago in the middle of my current role as a graduate school student. I spent weekend mornings doing research, late nights conducting interviews, and spare moments looking for typos.

Read the intro, Read Chapter 1, Read Chapter 2, Read Chapter 3, Read Chapter 4.

This chapter will cover the Oregon Way in its earliest conception—from the features of Oregon’s resettling on through William U’Ren and the Lewelling family fighting for the initiative and referendum. Readers will learn about what brought resettlers to the state and explore why the work of the state’s first generations of leaders were so important to future Oregonians eventually establishing the Oregon Way. Still, blatant flaws, such as racism and political extremism, prevented the realization of the Oregon Way in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Some leaders, though, occasionally transcended these flaws and helped nurture the norms, values, institutions, and processes underlying the Way.

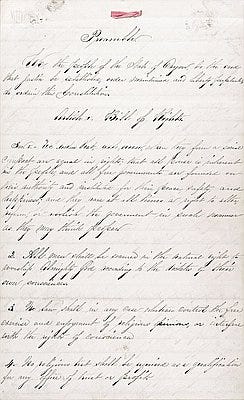

The demographics of Oregon’s constitutional convention, the origin of the constitution’s legal principles, and the political aspirations of the state’s earliest resettlers all factored into how future Oregonians would develop the state’s Way. A summary of the events leading up to and occurring during the constitutional proceedings shows how the Father of the Oregon System, the Oregon Way’s predecessor, William U’Ren could lead the state and move it closer to possessing a cohesive political culture.

Resettlers—Who They Were and Why They Came

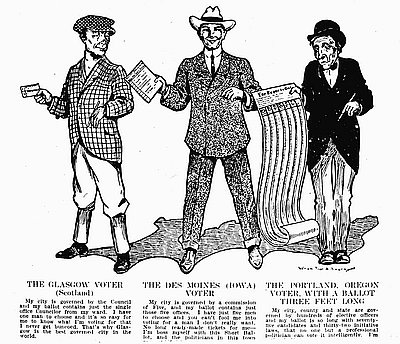

Oregon imported its legal underpinnings. Resettled by Midwesterners with varied levels of legal awareness, especially in the context of constitutional writing, the men tasked with turning a territory into a state did so with a lot of copying and pasting. Lazy or resourceful, the legal frameworks that created Oregon came from far beyond the nascent state’s borders. The lineage of the state’s laws can be traced through the Midwest (especially Iowa) and even further afield to the cantons of Switzerland.

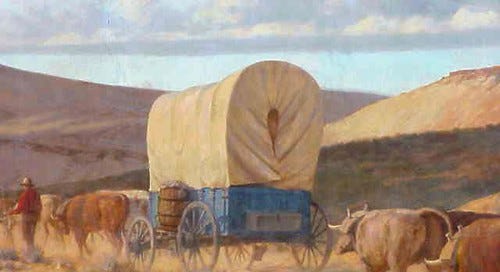

The promise of enough land to provide for your family for generations lured Midwestern farmers out of Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Ohio and on to Oregon. They took the Oregon Trail in search of stability. Midwestern farmers had grown tired of the volatility associated with trying to compete in a globalized commodities market. The 1837 recession reinforced that unpredictability. Farmers struggled to remain profitable amid dropping prices caused by a now global supply of produce. The families with sufficient means to skip a farming season (or two) set out on the Oregon Trail.

Legal incentives likewise encouraged family-based migration. The Donation Land Grant provided 320 acres to single men, but a total of 640 acres to couples. The 640-acre plots were later found to sustain approximately the next four generations of your family. The Act, then, made it somewhat nonsensical to resettle in Oregon absent a significant other—given the doubling of land that was possible by virtue of having a spouse. Migration demographics reflected this reality; resettlers rarely came all the way to Oregon in isolation. Consider that in Salem, 86 percent of residents lived in nuclear households. The law, the length of the journey, and the values of those considering the trip all disproportionately brought families to the Oregon segment of the overland trails.

With so many people thinking about the long term well-being of their kin, a conservative attitude defined and distinguished Oregon. “[T]his desire for stability and continuity [among resettlers] made Oregon something of an anomaly in the otherwise unbridled Far West of the mid-nineteenth century,” based on research conducted by David Peterson del Mar. In retrospect, the state’s heightened conservatism is not much of a surprise. Oregon was home to resettlers from similar areas with similar goals all living in a small sliver of the state. The Willamette Valley acted as a geographic and ideological funnel. It directed people to the same area of the state and eased the exchange of similar values. The dense concentration of early resettlers in the Willamette Valley was so strong that it has perpetuated population density patterns that are still evident today. In 1860, “Eastern Oregon’s Wasco County covered about half the state but included barely 3 percent of its non-Indian population.” Since then, not much has changed about the geographic distribution of Oregon’s population.

The common origin, shared demographics, and overlapping motivations of Oregon’s resettlers permitted a relatively seamless transfer of the Midwest’s political culture to the young state. An early description of resettlers’ norms and social institutions from del Mar indicates how quickly certain facets of the Oregon Way became a part of the state’s political culture:

Progressive Willamette Valley farmers had begun forming societies and organizing fairs in the 1850s. Here they shared tips for more effectively producing crops and livestock and awarded each other prizes for the best products. The first state fair was held in 1861. But these meetings soon turned from discussions of how to produce the most bushels of wheat per acre to lamentations over the transportation monopolies of the Columbia and Willamette rivers, companies whose high freight rates eroded farmers’ profits and raised the cost of their machinery.

Unpacking this description shows that resettlers prized social institutions that facilitated exchange of information and goods, detested anything remotely associated with “bigness” such as railroad company largess, and valued trading political views as well as farm goods.

Put differently, the majority of the territory’s resettlers “hailed from the Midwest, where the [Jacksonian Democratic] party was strong. They favored individual enterprise and liberty and distrusted merchants, banks, manufacturers, urbanization, and reformers.” This preference for individualism reflected living on isolated plots of land, which facilitated the emergence of small social and economic communities. The disdain for markets came partially from prior negative experiences in the Midwest and partially from the absence of such markets in the distant Oregon territory. Even if Oregon’s early farming communities proved incredibly productive, the dearth of sufficient transportation options to get goods to market incentivized merely producing enough for you and yours.

A Constitution by Resettlers, for Resettlers

When it came time to enshrine some of these values and norms into a constitution, Oregon’s early officials demonstrated both the positive and negative aspects of their familial style of daily and political life. Matthew Deady, central to the formation of Oregon as a state, expressed a version of individualism paired with localism that resonated with others; it was a formation many of them grew up with—82 percent of Oregon’s constitution writers had lived in Midwestern states with those cultural traits before heading to Oregon. Delegates conjured these traits when formulating the state’s laws and provisions. Deady and his followers moved forward legal structures that built on their old systems and mitigated what they viewed as threats to their clannish conception of daily life. (Read David Frank’s earlier post on Deady to learn about his flagrant and egregious racism).

The limited demographic and, in many cases, ideological scope of Oregon’s political sphere meant that the involved stakeholders did more together than just act on their political similarities. Salem became a social scene for individuals representing every part of the governing universe. A visit to the Plamondon Saloon in the 1850s would have included seeing legislators, press members, and lobbyists going over the latest news and gossip. Individuals like George Williams, one of the most significant contributors to Oregon’s Constitution, nurtured the budding network of officials and politicos. As a judge, Williams would eagerly adjourn a day in court so that he could commence a night of dancing, per David Alan Johnson’s historical investigations. Williams’ proclivity for partying illustrated that official business with friends, neighbors, and/or distant relatives regularly became informal socializing. These after-hours gatherings fostered a family-like atmosphere in the state’s capital; not everyone agreed on the contentious issues of the day but most could still find a connection through shared values and norms that at least counteracted any political distance between them. This familiarity likely influenced the degree to which Oregon’s Constitution conveyed the personalities and personal histories of its authors.

The Constitution contained several hints to the predisposition of its creators. A preference among Constitution writers for elections to offices over appointments signaled concern over an isolated governing class that could perpetuate a narrow membership [these men, like their revered Thomas Jefferson, prioritized trusting the people over any sort of aristocracy]. Their preference for shorter legislative sessions came from fears of longer sessions fostering legislative logrolling. The Constitution’s authors also imbued local communities with substantial powers and limited the state's ability to override community-driven decisions. Racial bias among the writers contributed to Oregon becoming a free state in two senses: free of slaves but also free of blacks, who were banned from residing there. Overall, in Johnson’s opinion, the document expressed the values of racist, Jeffersonian Democrats. Its provisions conveyed “an emphasis on local sovereignty and grass-roots organizing, an independent producer ethic, and what Michael Hold has called the ‘doctrine of the negative state.’” This latter concept can be understood as individual protection from government intrusion.

The Fate of Non-Resettlers

The interplay between the land, the law, and the lineage of Oregon’s resettlers continued to shape political events in 19th century Oregon. Beyond crafting a Constitution meant to preserve the specific attributes (physical, demographic, and economic) that brought the homogeneous resettlers to Oregon, these new residents developed a layered society to maintain what they saw as Oregon’s strengths. “The public life and political institutions they fashioned,” writes Johnson, “were closely related to their rural ways. Marked by face-to-face relationships, conducted by well-known friends and neighbors, politics here [in Oregon] expressed the settlers’ common culture and provided the focus of a community life otherwise attenuated by rural isolation.”

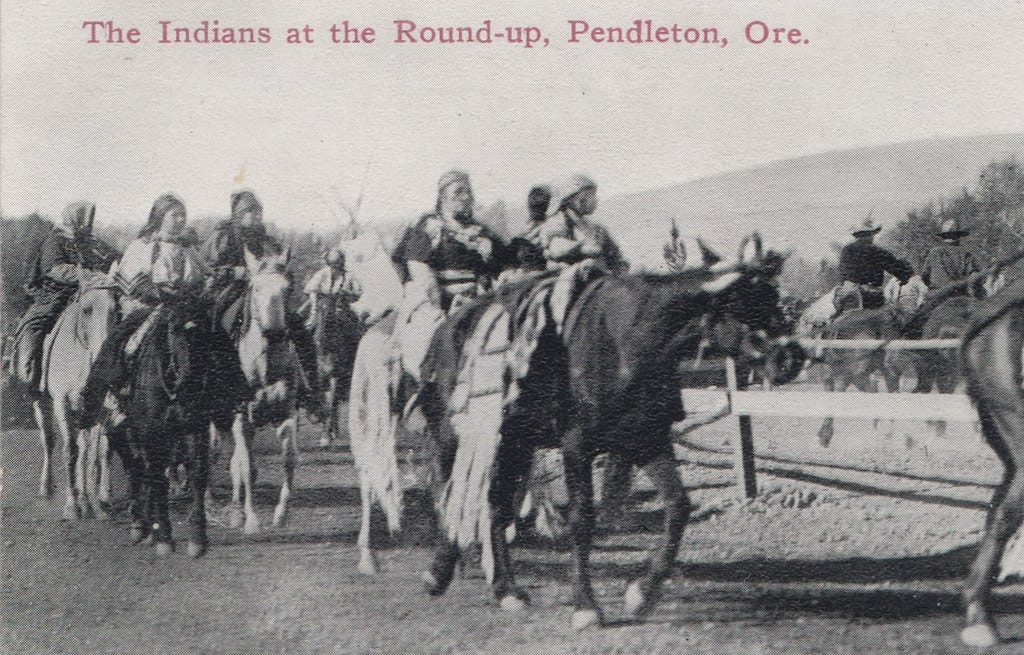

For all its faults, the resettling era marked the earliest signs of the Oregon Way. Prior to the resettlers, Native American tribes, missionaries and traders filled the territory. These prior residents, though, were denied the opportunity to make their values, norms, institutions, and processes a part of Oregon’s founding as a state. The flood of resettlers of similar stations and beliefs into a narrow slice of Oregon crowded out many of the communities that had once played a more sizable role in shaping Oregon’s economy, governance, and environment.

Traders and missionaries suddenly became vestiges of the past. Several factors beyond a mere deluge of resettlers moved these populations and their values to Oregon’s annals. The pelt trade became less and less profitable; traders drove beavers to near extinction in parts of Oregon, which pushed the trade elsewhere. A misalignment of values between resettlers and traders and missionaries hastened the exclusion of the latter groups. Where conflicts over these values took place, resettlers usually won. Consider the plight of John McLoughlin, once one of Oregon’s most celebrated traders. He lost prime real estate near the Oregon Falls on the Willamette River because of a dispute with resettlers over what it means to truly own land. Though McLoughlin had adhered to the laws of the time, the resettlers’ hunger for land—strong enough to carry them over mountains—proved insatiable; they ignored the norms and laws of McLoughlin, other traders, and missionaries. The numerical might of resettlers, amplified by their cultural opposition to trading and religious activity, meant that traders and missionaries soon had little physical and cultural space in Oregon.

As evidenced by constitutional provisions and resettlers’ treatment of religious entities and individuals, the once widespread practice of proselytizing in Oregon died out fairly quickly with the emergence of new laws and cultural expectations. Religious groups, like the traders, had their territory squeezed and way of life challenged. And, just as an anti-commerce mentality remained apparent well after resettlers had established themselves in Oregon, the resettlers’ animosity toward religious Oregonians persisted and eventually informed every aspect of the Oregon Way.

Though Oregon changed for traders and missionaries, it was stolen from Native American tribes that called the area home long before anyone thought of taking a wagon over the Rockies. A full dive into the horrendous treatment of Oregon’s original settlers is beyond the scope of this book. The arrival of whites, initially celebrated by some tribes that mistook folks such as Meriweather Lewis and William Clark for prophesied agents of a new, glorious era, resulted in the physical, economic, and spiritual destruction of nearly every tribe. Native Americans arguably never had a chance to shape the early contours of the Oregon Way.

The beginnings of the Oregon Way aligned with a period of drastic change in who called Oregon home. The traditional story of the Oregon Trail celebrates this transformation in population as a testament to the perseverance and vision of America’s pioneers; like most stories, this rendition mixes truths and blatant lies into a narrative that was morally palatable and, for that reason, easier to share. A competing story, one grounded in empirical evidence, documents not a fairytale with heroes riding in wagons, but a nightmarish invasion that accelerated the demise of a complex and refined ecosystem.

The latter story does not easily lend itself to integration with the Oregon Way. Homogeneity, forged through the exclusionary practices retold in the nightmare version of Oregon’s history, was essential to resettlers creating a distinct political culture. Resettlers often used Native Americans and minorities as political props from which they could maintain some degree of unity among white residents. The remainder of this chapter and book will focus more on the traditional story because of the centrality of that story’s heroes and subplots to the creation of the Oregon Way. This unfortunate reality underscores that distinct political cultures for an “us” often come from defining and, in many cases, prosecuting a “them.” As will be explored in greater detail throughout the book, the correlation between homogeneity and idiosyncratic politics is high in Oregon. How to define and unify around an “us” while still creating a progressive political culture that is different from the norms and values of “them” is a conundrum as vexing as the Snake River is windy. Officials past and present have struggled to update the Oregon Way while simultaneously broadening it to accommodate increasingly diverse Oregonians.

The Oregon System and Early 20th Century Oregon

As the constitutional period of Oregon’s history came to a close, legal and cultural barriers meant that the political sphere remained relatively homogeneous. At this point in Oregon’s history, both the political establishment, grassroots activists, and many social institutions could find their footing on the same Oregon Way, which is to say that they shared a tremendous amount in common in terms of norms, values, and conceptions of proper democratic processes. The broad coalition that promoted the Oregon System illustrated the congruence of values and norms across varied groups (at least among those that were allowed to participate in Oregon’s politics).

As mentioned in the previous chapter, U’ren and Bourne had different backgrounds and represented disparate populations but still united in driving Oregon toward a more participatory government. Their success in realizing the Oregon System also tapped into an even broader network of people eager to trade ideas and exchange the latest political books. This network included the Grange and the Farmers’ Alliance and relied on regular Oregonians, such as the Lewellings, opening their living rooms for meetings and organizing sessions for various initiatives. From these meetings, organizers launched a massive educational campaign. U’Ren and others delivered informational packets throughout the state while extensively lobbying legislators. The mosaic of interests involved in the initiative effort speaks at once to the charisma of U’Ren and the substantial overlap of values and norms at this time.

That said, depending on who you ask, U’Ren had to rely on some questionable tactics to get the System into place. The eventual adoption of the Oregon System required U’Ren to surrender his ties to partisan groups. Depending on the political tides of the day, U’Ren would abandon one coalition for another, depending on which was better suited to realize the System. It is likely that some politicos, then and now, would call him a disloyal political actor while others would praise his fidelity to an idea larger than any one party. This tension between being a “team” player and standing up for a specific value has often complicated the actions of esteemed Oregonians. It appears U’Ren found the right balance of the values—after all, history looks fondly on U’Ren because the System contributed to the development of the Oregon Way. But this wasn’t the only needle that U’Ren needed to thread.

The Father of the Oregon System also had to weigh improving a process within a flawed democracy against improving the democracy itself. Oregon’s democracy at this time was defined more by who it excluded than who it included. U’Ren could have agitated for expanding enfranchisement but instead opted for expanding the rights of those already allowed to vote. He made the easier choice by selecting the latter.

Of the Oregonians allowed to engage at this time, few had wildly different upbringings and backgrounds. Oregonians in the civic sphere at this time appeared to be just fine with giving themselves more influence. The similarities among voters likely moderated their policy stances. This may explain why U’Ren was able to secure the legislature’s support for the Oregon System, earn 90 percent of the public’s support, and implement the System without it producing any radical outcomes.

The profound conservatism and clannish nature of the Oregon populace meant that even when granted with expanded political power made possible by the Oregon System, the people of Oregon used the initiative and referendum in relatively moderate, sensible ways. They employed the initiative to make the legislature more responsive (allowing them to more easily refer constitutional changes to the people) and more accountable (subjecting legislators to the possibility of being popularly recalled); and, they moved to make elections less corrupt (see the Corrupt Practices Act). So even when handed a blunt instrument with few instructions, common values and norms among homogeneous Oregonians meant that voters initially wielded the Oregon System with care. If they were reckless, then the recklessness revealed itself in voters’ willingness to entertain a lot of ideas. By 1912, there were thirty-seven measures on the ballot, most of which were submitted by initiative rather than through legislative referral.

The traditional story of Oregon shies away from the fact that the limited diversity of Oregon residents and political actors was a factor in the creation of the Oregon System. Big money and minority movements with the potential to sway Oregon away from the System did not exist. The slow development of industry in Oregon, a byproduct of the state’s culture and laws, meant that an elite class had yet to amass sufficient power to stem the populist sentiments of U’ren and Bourne. Minorities and even resettlers from different parts of the country had similarly yet to ascend to higher levels of political influence and introduce complicating variables to coalition- and consensus-building such as different political norms and new social institutions.

Indeed, the largest social institutions of the era, such as newspapers, reinforced the insularity of the Oregon political system. Editors of the largest papers had tight relationships with the legislators of the day. Though incestuous, this dynamic permitted certain ideas to quickly become consensus actions approved by the state’s small, controlling social and political circles. The homogeny-induced alignment of values and norms also expedited Oregon’s movement toward less celebratory outcomes.

The State of the Oregon Way into the 1920s

Even as the state moved into the 1920s, Oregon remained a “small” state in the sense that the population continued to be white, Willamette Valley-based, mainly agricultural, and still influenced by the ideas (and, in some cases, progeny) of the original resettlers. When the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) reemerged with an emphasis on anti-elitism and anti-Catholicism, in addition to its historic focus on racism, many Oregonians readily joined. The KKK presented residents with a vehicle through which to fight back against changes—commercialization, diversification, and religionization—that they felt threatened their core values and norms. Though historians debate the predominant focus of the KKK in Oregon, each landing on a different part of the spectrum from an anti-elite focus to anti-minority focus, the pervasive influence of the organization signaled how homogeneity in the state could act as a catalyst for defensive, hasty, and hateful political outcomes.

If you were white at this time, then it likely would have seemed as if the Oregon Way had actualized each tenet of a Way. But the Oregon Way did not realize its potential in the first fifty years of the state’s political history. It failed to reach its potential because it was based on a narrow definition of “us.” For those within “us,” the Oregon Way seemed to be working perfectly: strong social institutions, shared values and norms, and “open” democratic processes facilitated the creation of broad coalitions that passed significant legislation and formed impactful political forces. However, the exclusion of so many Oregonians (as well as would-be Oregonians) meant that the Oregon Way in these decades was too narrowly construed; the Way was built upon an unsustainable (not to mention, unethical) ability to marginalize “un-Oregonian” communities and control migratory patterns.

Oregonians in the “us” group did not just celebrate their affinity for one another, but actively opposed “them.” “Us” resented “western carpet-baggers”, as coined by Earl Pomeroy, and tried to limit the inmigration of non-whites. And, when in-migration did occur during this era, the “us” bunch reinforced the state’s demographic homogeneity. The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909, for example, opened up the door to unoccupied land in Oregon but the door only opened wide enough for a particular kind of resettler. Midwesterners and Pacific Northwest residents that presumably shared many aspects of Oregon’s political culture were the ones that came into the state through this crack in the door.

Meanwhile, officials at the state and local levels continued to exclude homosexuals, African Americans, Chinese and Japanese migrants and several other communities from full participation and, when possible, entrance into Oregon. Consequently, wins for the majority of Oregonians (the “us” bunch) commonly took place concurrently with losses (spiritual, physical, economic, cultural, etc.) for minorities, lumped into a denigrated “them”.

Governor Oswald West’s record exemplifies the paradoxes associated with this early stage of the Oregon Way. Modern Oregonians know Governor West for the sort of future-oriented, pragmatic, and conservationist actions expected of the state’s Way. In response to calls from environmentalists and business groups for greater environmental protection of the coast, the Governor applied each aspect of the Oregon Way to find a legislative path forward. Governor West patiently listened to the viewpoints of involved stakeholders such as William Finley (a dedicated conservationist and preservationist), followed norms of incorporating these views into his decision-making processes (for example, by bringing folks like Finley into the government via the newly-formed Oregon State Parks Commission), and applied an innovative, long-lasting approach to ensuring the outcome would withstand political vicissitudes (in this case, designating the beaches as a public highway so that the Department of Transportation could ensure its accessibility). More than a century later, Oregonians have unrivaled access to their coasts thanks, in part, to Governor West’s adherence to the Oregon Way.

West’s contribution to the Oregon Way should not overshadow his fight to punish the growing number of Oregonians he viewed as “them” for their demographic and cultural differences from “us.” Reports of homosexual activity in downtown Portland generated a draconian and intolerant response from Governor West. In 1912, rumors spread that Portland housed a gay male subculture. Political powerhouses, including the Governor as well as then-Congressman William Lafferty, turned these rumors into a political opportunity to jab their opponents—wealthier Portlanders and more radical populists that frequented the area of Portland in question [both groups strayed from the ideals of resettlers’ conception of Jeffersonian Democracy; the former being too aristocratic and the latter being too urban].

Referred to as the Portland Vice Scandal, Governor West responded to these “troubling” reports by approving legislation that extended the sentence for sodomy. He also used the scandal to pass House Bill 69, which permitted the sterilization of "sexual perverts." The scandal had a significant impact, not just on Oregon but up and down the West Coast. Such a broad and quick response would not have occurred absent the tenets of the Oregon Way accelerating a discriminatory response. Social institutions, such as labor groups and local newspapers, ensured that the shared value (or bias) for homogeneity (sexually, demographically, and politically) was enforced, which quashed an emerging cultural norm.

Comparatively, as will soon be displayed, the Oregon Way at its zenith in the 1970s fostered shared values, enforced norms, and independent social institutions that incorporated a much larger (though not comprehensive) set of Oregonians. This set was able to act on shared values and norms in conjunction with social institutions through democratic processes far more accessible than those that existed in the state’s initial decades. The process of broadening that involved the definition of homogeneity—the process of expanding “us” and reducing attacks against “them”—started with removing some of Oregon’s most egregious forms of de jure and de facto discrimination.

*********************************************

Send feedback to Kevin:

@kevintfrazier

Keep the conversation going:

Facebook (facebook.com/oregonway), Twitter (@the_oregon_way)

Check out our podcast: