RtOW: Chapter 8, Part I - The Beginning of the End of the Way

How divided did Oregon become? One reporter labeled it the “Mideast” of America- “the land of the angry and the scared, the right and the righteous."

*Editor’s Note* For the next several weeks, I will be posting one excerpt from my book, “Rediscovering the Oregon Way.” This effort started two years ago in the middle of my current role as a graduate school student. I spent weekend mornings doing research, late nights conducting interviews, and spare moments looking for typos.

Two Case Studies as an Introduction to Oregon’s Transition from the Oregon Way

Contemporary wisdom suggests that when Speaker of the House Vera Katz, a Democrat from Oregon, saw the 1990 election results, she should have been irate. Voters flipped her legislative chamber to the Republicans, which today would mean that her priorities for the next legislative would be dead in the water. The partisan flip of control over a chamber usually results in the new majority attempting to upend whatever the prior party had attempted to accomplish (this is most obvious at the federal level with Republican’s treatment of the Affordable Care Act).

But conventional wisdom failed to overturn the Oregon Way. The newly elected Speaker, Larry Campbell, a Republican from Lane County, opted not to actively oppose Katz’s priorities for the sake of partisan gaming. Instead, the duo collaborated to pass the Oregon Education Act for the 21st Century also known as Katz’s Bill. The Act extended Oregon's school year, enacted new measures for instructional accountability, created alternative learning centers, and provided full funding for Head Start. Bipartisan support for a bill with many contentious provisions evidenced that the Oregon Way persisted from the 1970s on through the early 1990s. But a noted decline in the strength of the Way loomed ahead. By the 2000s, drastic changes to the state’s values, norms, social institutions, and democratic processes had come to fruition. The result was the development of a political culture that channeled national-level discord and disunity more so than similarities among Oregonians.

In the 1999 session, the room for moderation and collaboration had already been reduced to the size of a San Francisco studio. In marked contrast to the constructive transition of power between parties at the start of the decade, Republicans within the Oregon House could not even manage a positive transition within their own party. Lynn Snodgrass—a staunch conservative representing Boring, Happy Valley, and nearby communities and who had little sympathy for priorities favored by Democrats—deposed Lynn Lundquist, the previous Speaker of the House who had been accused of being too closely aligned with Democratic aims. In Snodgrass’ opinion, Lundquist was far too willing to sacrifice the deeply held values of conservative Oregonians for broader compromises that incorporated more widely-held values. While some, such as Representative Bob Jenson, R-Pendelton, characterized Lundquist as the personification of “the idea of speaker of the House, not speaker of the Republican Party,” that nonpartisanship became a liability to Lundquist’s political future.

The Snodgrass takeover solidified troubling norms and exclusionary democratic processes in the chamber. No longer was it acceptable for a Speaker to find 31 votes of any party affiliation to pass legislation; now that coalition had to be solely one of party members. Speaker of the House Bev Clarno, who presided over the chamber from 1995 to 1996, first oversaw the use of this rule—no bill would be introduced without party support sufficient to carry it to passage—but Campbell’s insertion into the office confirmed the staying power of the “Clarno Rule.” With these rules in place and unifying norms and values missing from Salem, not even social institutions could keep Oregon centered on its Way nor were they in a position to. Throughout the 80s and on through the 90s, social institutions traded their independence for partisan influence—many came to overlap with the political party nearest their value set and moved away from moderate stances. The four legs of the Way, then, were struggling to maintain their strength.

This chapter will explore how the tenets of the Oregon Way persisted through the 80s and into the 90s, how the Way withered as partisanship became more potent as the century closed, and which specific legislative episodes best illustrate the aforementioned developments.

Timber and the Way

The late 1970s portended the difficulties facing the strength of the four legs for the following decade. “A sharp downturn in the state’s economy during the mid-1970s,” per David Peterson del Mar, “made the state’s vaunted ‘livability’ seem like a luxury that many Oregonians could not afford.” Though the perceived decline in livability was moderated by economic gains in the mid- to late-80s, the specter of Oregon’s quality of life becoming unattainable left an indelible mark on many Oregonians.

This mark manifested itself in initially subtle but eventually unmistakable changes in Oregon’s economy, culture, politics, and social fabric. The degree to which these characteristics changed was correlated with the vibrancy of ties between rural and urban Oregon. When the timber industry experienced a crash in the late 1970s, strains in the rural-urban ties appeared; those strains eventually became seemingly irreparable breaks in the relationship between Oregon’s two communities.

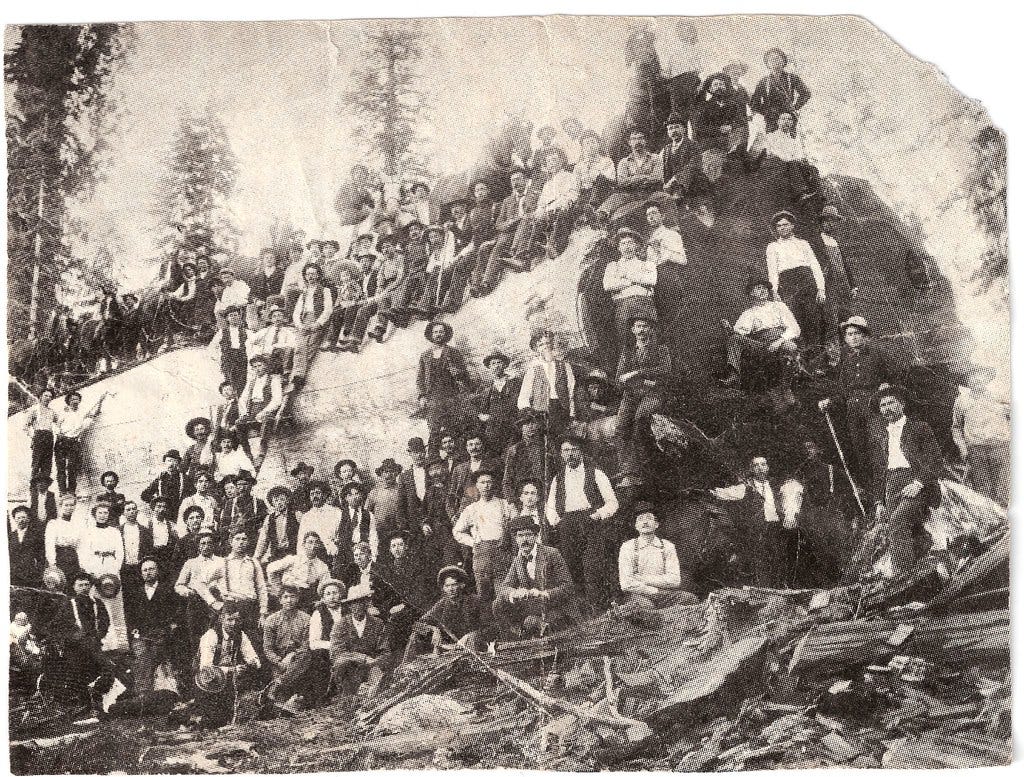

Timber production was at the heart of many Oregon communities. A source of employment for several generations, family trees in these communities were both figurative and literal. Members of these families lived in communities where the roads, the cadence of daily life, and the politics revolved around timber. Strong bonds to the logging industry were not confined to rural areas. Urban areas, such as Portland, also had ties to timber. Timber provided a common source of well-being and economic development in communities around the state. The ubiquity of timber-based employment meant that many Oregonians shared a connection through the industry—a connection that frequently brought urban and rural residents together in the context of executing their respective roles of the timber development process. In the heydays of woodworking, the timber industry accounted for 1 out of every 10 private sector jobs in Oregon and 13 percent of all private sector wages. And, these weren't just run of the mill jobs...wages in the timber industry beat the statewide average by more than 30 percent.

Social institutions reinforced the sense of community generated by widespread timber employment and affiliated outdoor activities. Organizations such as 4H and sportsmen groups regularly sent young and old urban Oregonians out to the rural parts of the state to engage in everything from summer camps to general recreation. During this time, around the late 1970s, Carl Abbott recalled that Friday nights at the start of elk season filled I-84 with east-bound traffic as Portlanders headed to the hinterlands to join with their hunting buddies and clubs. So formal and informal activities generated a norm of exchange and interaction between people on either side of the Cascades.

These interlocking sources of connection helped Oregon stay on its Way. Though urban and rural differences still emerged in Salem, Oregonians remained fairly close to one another on the political spectrum: coalitions of urban and rural legislators frequently formed; party registration rates did not vary tremendously from county to county; and statewide candidates often received support from nearly every county, regardless of their party affiliation. This level of political similarity helped legislators advance legislation that equally frustrated urban and rural residents (remember Roblan’s refrain that strange bedfellows makes for good policy).

This Way-informed status quo crashed when the timber industry nose-dived. A nationwide recession in the early 1980s felt like the Great Depression in the acutely affected rural counties of Oregon. Brent Walth observed:

In some rural counties, one of every six workers was without a job, the worst unemployment since the Great Depression a half century earlier. The recession hollowed out small towns and smashed middle-class dreams, and many families who had cut their living from the Oregon woods for decades fled or splintered.

Within the span of a single decade, 1979 to 1989, the economic fairytale that was the Oregon timber industry became a much sadder story; based on research by the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis, timber industry jobs in 1989 had dropped 17 percent compared to just a decade earlier. Those losses have persisted. By 2017, direct employment in the timber industry had decreased by 60 percent since the 1970s; wages similarly dropped—landing at just around the statewide average.

The foundational struggles of timber communities left legislators with few good options to restore their economic well-being. Automation and international trade had changed the nature of timber production. These evolutions in the industry were beyond the control of any governing body, especially Oregon’s state government. Nevertheless, timber communities expected and needed more help than they received. The space between what was provided by the government and requested by rural communities became fertile ground for growing discord.

The gulf forced social institutions and legislators to take sides: uphold the timber industry or recognize its demise and help rural communities diversify their economies through more sustainable industries. This separation decreased the number of social institutions with statewide appeal. Each side—timber and environmentalists—expected other entities to go out of their way to signal which side they had selected. At the height of the division over how best to use Oregon's resources, Governor Neil Goldschmidt sadly stated, "There is no middle ground." Fervent supporters of the timber industry, for example, boycotted local stores that did not readily display a yellow ribbon—a signal of loyalty to timber communities. The animosity between the two sides led one L.A. Times reporter to call Oregon the “Mideast” of America, “the land of the angry and the scared, the right and the righteous.”

Organizations as elemental as tire shops felt it necessary to tie themselves to one side of the divide—making appeals such as "Support Our Timber Industry" a part of their newspaper ads. Meanwhile, in urban communities and on college campuses, social institutions on the other side of the divide flourished: del Mar recounted a "growing array of radical and reform groups continued to work at transforming Oregon politics and society," and specifically pointed out that "[c]ollege campuses housed scores of eclectic organizations: recyclers, Black and Latino student unions, women's centers, and many, many more."

As social institutions picked sides, separate ideologies started to develop and become associated with each group. Some Oregon communities embraced technology, such as semiconductors, as their economic livelihood, others came to despise both technology and increased government regulations that made it harder for Oregonians to find employment in the timber industry. Each of these ideologies fostered different norms and values. For instance, something celebrated in Albany—like a timber carnival that brought the community together—would be derided and condemned in the Alphabet District of Portland. Similarly, different communities had different “heroes,” slogans and signs, and apparel to make it abundantly clear how they perceived the conflict. Where one stood on the timber question was something that got at the very “self-image” of Oregonians. Consequently, the pull of social institutions and divergent norms and values resulted in Oregonians no longer sharing a common approach to solving problems nor a set of broad policy objectives to pursue. “A war,” as labeled by some East Coast papers, such as The Harvard Crimson, ensued. All in all, "[t]he yellow-ribbon campaign of the late 1980s and early 1990s swept small, timber-dependent communities," but, according to del Mar, "caused hardly a ripple in metropolitan Oregon."

Democratic processes soon became the weapon of choice for ideological battles. As discussed below, the initiative became a test for which side you belonged to, the state legislature hosted wars that turned on the depth of narrow ideologies rather than the breadth of widespread ideas, and the tenor of campaigns became uglier as candidates tried to appeal to ever greater extremes. Take, for example, Harry Lonsdale, while running against Senator Hatfield, comparing Oregon to a "Third-world" country based on its timber exports to Japan, which created value-added products from the wood. Politicians like Lonsdale opted to intervene in questions related to forest growth management plans that used to be resolved in a fairly mundane, bureaucratic way by the Forest Service. It follows that elections and other processes became platforms for voicing partisan positions rather than opportunities to identify shared values. Even democratic processes as seemingly straightforward as appeals to the Forest Service were co-opted and flooded by the extremes of the timber debate. Between Oregon and Washington, the Forest Service received an average of one administrative appeal per day in 1990.

It is not fair to pin the fragmentation of urban and rural communities entirely on timber. Indeed, differences between urban and rural communities have been around for the entirety of Oregon’s resettled history. In the 1850s, Marion, Polk, Linn, Benton, and Lane counties accounted for a majority of the population, 80 percent of the worked acreage, and more than 67 percent of the recorded value of farm land. More than a century later, urban communities continued to have a disproportionate share of economic activity. The difference was that even economically divergent communities in the 1850s depended, in part, on one another. In the 1990s and 2000s, urban communities became nearly self-sufficient as the economy moved away from natural resources.

The collapse of the timber industry was always on the horizon but infrequently on the agenda of state officials. As early as the 1950s, it became clear that timber's mark on Oregon's economy was destined to fade. By that decade, forests in the northwest part of the state had nearly been depleted. The logging footprint shrunk as a result and moved into the southern regions of the state.

How Moderates maintained the Oregon Way: Verne Allen Duncan Case Study

As the timber industry was uprooted, a unique kind of leadership style kept the state grounded in the Way, even if by a thread. The leaders that demonstrated this style were relatable to the struggling logger, the striving urban laborer, as well as the litany of folks just moving to the state. These leaders were the progeny of McCall and Hatfield.

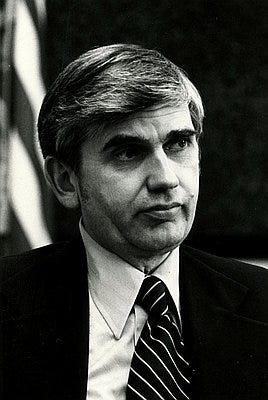

One such descendent was Verne Allen Duncan. Contemporary Oregonians have likely never heard of Duncan but he deserves to be mentioned concomitantly with McCall and Hatfield. He embodied the Way while serving as the state chief education officer from 1974 through 1989 and, later, in the state legislature. Duncan crossed off each attribute of the Oregon Way. His politics catered to identifying shared values—he was a “moderate’s moderate.” His style of leadership facilitated democratic participation—he spent half a day every week with students and administrators when he was leading the state’s education effort. His commitment to every community in Oregon signalled a norm of equally valuing the voice of every resident—he visited every single school district (all 301 throughout the state). Finally, while he was in the legislature, his deference to legislative committees and community organizations evidenced a high regard for institutions.

Like a massive counterweight in a skyscraper, Duncan stabilized whichever institution he joined from swaying too far in any direction. This leadership quality was developed outside of Oregon but nonetheless helped the state during the aforementioned turbulent times. Though an Oregon native—born in McMinnville, Duncan developed his distinguished leadership style in Idaho. For twelve years, from 1954 to 1966, Duncan served as a teacher, principal, and superintendent of schools in Butte County. He additionally served in the Gem State's legislature from 1963 through 1966. Upon return to the Beaver state, Duncan did not forget to pack his pragmatic approach to governance. It was an approach that caught the eye of Oregonians. Only eight years after returning to Oregon, Duncan earned sufficient support to win statewide elected office in 1974.

In those eight years as well as while in office, Duncan did not waver in exemplifying the Way’s characteristics, even when it may have been politically expedient to do so. Case in point, despite knowing he had a tough re-election fight ahead of him in 1978, Duncan did not bend to the will of lobbyists and major political influencers such as the Oregon Education Association (OEA). The organization opted not to endorse the incumbent because of his position on strikes and arbitration. The re-election battle would have been much easier with the OEA's backing...it was (and is) an understatement to merely call the organization "powerful," especially when dealing with blatantly educational matters. Yet, Duncan forged ahead.

In 1997, when Duncan was appointed to the Oregon House, Duncan again used his principles to gain political clout. Defined as a “pragmatic Republican” and celebrated as a son of McCall-style politics, Duncan’s presence in Salem showed voters that despite discord at the national level there was still a space for centrist Oregon officials. His presence showed other legislators that centrism and compromise were not dirty words, a fact illustrated by his rise through the legislative ranks. Before ending his time in office in 2003, Duncan had served as the assistant majority leader and oftentimes as the chair of the most powerful committees, including the Government Affairs, Judiciary, and Legislative committees. He advanced despite not viewing politics as a competitive sport...his goal was never to “win” so much as to advocate for the best outcome. According to Duncan, “Sometimes it doesn’t hurt to lose. It keeps you humble.” This moderate approach paid off for Duncan and the state. Just as in the 70s, an ideological flexibility provided officials with the space required to enact Way-aligned priorities.

Whether a paternity test would reveal Duncan as the father of “moderatism” in the 1980s is uncertain, but his behavior likely helped several other Oregon officials comfortably identify as moderate as well as voters to strongly support them. The emphasis of this label—moderate—may seem overdone and inaccurate when viewed through a modern mindset that’s been through the tumult of the Trump administration. Today, “moderate” in practice means slightly less partisan more so than actually independent from party influence. Though the share of contemporary voters that identify as independent has grown, the fraction of these self-described "moderates" who do not lean toward a specific party has actually shrunk since 1994. What is more, those who truly fall within the moderate category are less likely than their partisan counterparts to participate in elections; this means that modern moderatism is politically impotent and not necessarily a label elected officials feel the need to earn given the small electoral benefits of catering to such a pint-sized portion of the participating electorate.

Comparatively, moderatism in the 80s and 90s was a source of electoral and political power. It was an era during which "Oregonians wanted politicians to be conservative with their tax dollars but open-minded about how to fix problems..." So, in addition to Duncan, myriad other officials used the moderate label to earn and retain influence in the state. Vera Katz, a Democrat, did not shy away from compromising and working with Republicans; her willingness to find common ground with “opponents” such as Larry Campbell allowed her to achieve the landmark Oregon Education Act for the 21st Century, known as the Katz Bill. Katz defined herself as a "pragmatist" and a "realist," rather than tying herself to a specific ideology.

In practice, this meant "looking at the roots of the problems and trying to get to solutions that address [those roots], as opposed to fiddling around with the peripheral issues." It even meant allowing someone from another party—Nancy Ryles—to run for a higher office because Katz knew Ryles would do a great job. Hard to imagine any politician today passing up an opportunity to attain higher office, especially when doing so would result in a “win” for the other side. But Katz never categorized wins into Ds and Rs. She was willing to and insisted on "work[ing] both sides of the aisle," acknowledging her comfort not "follow[ing] in the footsteps of [her] own [democratic] caucus." Later, that same pragmatism allowed her to outmaneuver partisan stunts while she served as Mayor of Portland. It follows that she was able to accomplish a great deal, from the creation of the Eastbank Esplanade to the development of the Pearl District.

Katz wasn’t the only woman to make a mark through being moderate. Norma Paulus, a Republican, tapped into the electoral cache carried by a moderate label and similarly did not allow partisan blinders to stop her from seeing what was best for Oregon. While serving as the state's Superintendent of Public Instruction, Paulus praised the "Katz Bill" for providing the "rigorous, relevant education children need for success in life.” Support for bipartisan pieces of legislation was a just a part of Paulus larger pragmatic persona. Her death in 2019 sparked obituaries around Oregon that outlined the moderate approach that shaped her politics. According to OPB, she was "one of the most well-known politicians in Oregon" in the last decades of the 20th Century and was firmly anchored in the "moderate-to-liberal wing of the Republican Party." Paulus acted on her moderate mindset by trying to create social institutions capable of sustaining it. Early in her tenure as a state legislature, elected in 1970, she co-founded the bipartisan Oregon Women's Political Caucus. It was this sort of quasi-formal institution that moved politics away from strictly partisan understandings despite external pressures to more closely identify with party labels. The group formed a united front that led to the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. Katz, a member of the Women's Caucus, recalled that Paulus led the group and provided them with a common direction despite "some of the women [not having] quite agree[d]" on all the issues.

When Moderatism Ended? A Comparison of the 1986 and 1992 Elections

Beyond advancing moderatism and her own interpretation of the Oregon Way in Salem, Paulus’ run for Governor in 1986 showed that moderatism was even capable of shaping the character of elections. The election between then-Secretary of State Paulus and Portland Mayor Neil Goldschmidt had its flares and foibles but followed the Oregon Way nearly to a tee. The duo exemplified moderatism, which posed a challenge to voters looking for a way to distinguish between the two, but facilitated an election suited to two staunch adherents to the Way. However, by 1992 things had dramatically shifted as the Way’s values, norms, processes, and institutions transformed into unrecognizable legs of a harsh, partisan political culture. Just as the relationship between Campbell and Katz differed from that of Lundquist and Snodgrass, the juxtaposition of the 1986 election and the 1992 election highlights how a little time can make a big difference in a state as small as Oregon.

When it came to shared values, the gubernatorial candidates advanced platforms that appealed to both sides of the Cascades. The sensibility and centrism of their respective platforms was, to some, comical. Jim Redden, a reporter for the Willamette Week, observed that “[a]fter more than a year of full-time campaigning, the candidates still seem to much too much alike.” So much alike, in Redden’s opinion, that they should have considered a joint slogan, “Experienced. Competent. Interchangeable.”

It challenges the mind to think of two contemporary candidates having interchangeable stances. Such an occurrence would surely only occur after the Beavers win a national championship in football (never). The similarities in these candidates’ stances paired with their deep experience in Oregon politics signaled that the Oregon Way was still sourcing the best talent in the state well into the 1980s.

The strength of the Way also carried over to the norms that defined the election. For one, both candidates made a point of running truly statewide campaigns. For Paulus, this came somewhat easily. “For well more than a decade, Paulus had worked main streets, high schools, and banquet rooms across Oregon.” Goldschmidt, as an urban mayor and recent D.C. resident, labored to relate to the rest of the state but nevertheless made an effort to correct his urban bias and behavior. Additionally, both candidates opted for the high road. When presented with the chance to run a negative campaign ad, Paulus declined. Her fateful decision to initially decline the ad came from a consultation with her loved ones and close friends; she spurned the advice of political operatives. Paulus explained to her supporters that she’d rather “lose this campaign than run a negative ad and win.” Finally, the pair leaned on the state’s norm of participation. They hosted seven different debates that ensured voters had a chance to identify their preferred candidate.

These debates also added to the election’s support for open democratic processes and inclusion of social institutions. The candidates’ eagerness to make the election accessible to all mirrored the candidates’ backgrounds. As Secretary of State, Paulus had earned her statewide notoriety for staunchly defending democratic processes. “She gained heroic status,” per author and reporter Brent Walth, “in 1984 by preventing a massive voter fraud [at the hands of a cult in Central Oregon].” As previously mentioned, she also oversaw the earliest instances of vote by mail in Oregon. So it comes as no surprise that Paulus’ presence on the state’s largest electoral stage was matched with the involvement of Oregonians. The active solicitation of “average” Oregonians’ input and inclusion of their social institutions was similarly familiar to Goldschmidt. While serving as mayor of Portland, Goldschmidt championed the development of the city’s neighborhood associations. His office worked tirelessly to provide these associations with resources and guidance, as well as meaningful opportunities to express their views on city affairs.

The election captured the best of each candidates’ background but nevertheless did include some incidents that revealed cracks in the Way. For instance, though Paulus long delayed the use of negative ads, she eventually relented in an effort to recover from a less than stellar debate performance. In her defense, Goldschmidt's ads did not shy away from challenging Paulus' record. The Democrat ran ads early in the campaign that mocked her quips and muddied her record, accusing her of advancing new spending measures with no plan to pay for them. Though these ads would appear friendly by modern standards, they nonetheless evidenced a willingness to take a road other than the high one; the Way’s atmosphere of shared values lost a little air every time one of the candidates issued a low blow.

Those blows were empowered by a drastic increase in campaign spending. Both candidates raised tremendous amounts of funds that went toward their respective party’s infrastructure. As the parties grew in clout, other social institutions were crowded out and norms of principles-driven rather than party-motivated participation suffered. At the time, the race was the most expensive in state history. The duo collectively spent almost $5 million: Paulus spent $1.435 million in the general and $676,000 in the primary; Goldschmidt topped Paulus spending in both, by dolling out $1.602 million in the general and $1.277 million in the primary. This spike, most evident in the governor’s race, was apparent along the entire ballot. Consider that the cost of a state representative race in 1974 was $3,450. By 1986, that total had grown nearly seven-fold to $22,200. With a spike in spending came a shift in strategy that moved campaigns away from knocking on doors—the sort of activity that maintains a healthy norm of participation and conversation—and toward TV ads characterized by the sort of attacks described above. In the shadow of an election between titans, cracks in the Way were beginning to take hold.

Walth marks the 1986 election as the hinge that opened the door to a divided Oregon. Cracks soon became fissures. After 1986, parties lost sight of the Way and moved out of the democracy business; their focus, if ever on problem solving, was now fully on “winning”; they chased whatever values mobilized the most people to vote, not those that were shared among the most residents. Consequently, the Republican Party careened rightward and the Democratic Party deepened its dependence on and preference for urban issues. Money in politics, which rained in steadily for decades, became a deluge that washed norms aside and flooded social institutions with pressure to acquiesce to the partisan games. All of these departures from the Way were evident by the 1992 election.

***********************************************

Send feedback to Kevin:

@kevintfrazier

Keep the conversation going:

Facebook (facebook.com/oregonway), Twitter (@the_oregon_way)

Check out our podcast: