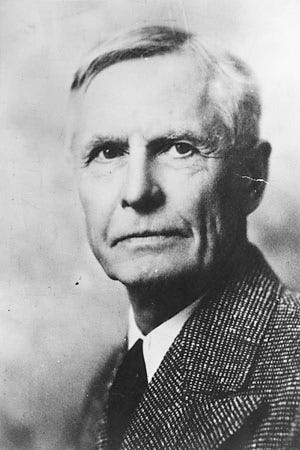

Tim Nesbitt: Calling William U'Ren

U'Ren launched the initiative process in Oregon in the early 1900s. We need to channel his focus on giving the people a chance to move the state forward in trying times.

Tim Nesbitt served as Chief of Staff for Gov. Kulongoski. A former union leader, he lives near Independence and oversees a specialty apple orchard.

Can a redesign of our century-old initiative process revitalize our democracy?

Photo of William U’Ren from the Oregon History Project.

Nationally, this election may be the most important of our lifetimes. By comparison, Oregon’s statewide ballot this year can seem surprisingly sparse and unresponsive to what troubles us most these days.

Despite the many problems we’re facing across the state, from the pandemic and wildfires to unemployment and homelessness, we’ll be deciding fewer ballot measures this year than in any general election since the 1960s. As I’ve reflected on this development, I’ve come to think that perhaps it’s time to refashion Oregon’s century-old initiative process to help revitalize our democracy.

Over the past three decades, we’ve been asked to weigh in on as many as 26 state measures on a single ballot; the average has been 12. This year, there are four, of which only two qualified as citizen initiatives. Yes, several signature gathering campaigns were stopped in their tracks by the Covid-19 lockdown. But, even so, there has been a marked decline in the number of initiatives that have qualified for the ballot throughout this decade, from an average of 10 per election cycle in the 2000s to an average of five in the 2010s.

I’d rate one of the two initiatives on this year’s ballot (Measure 110 – addiction recovery services) as far-sighted, well-crafted and compelling. And both of the legislature’s referrals to the voters – Measure 107 (campaign finance reform) and Measure 108 (tobacco taxes) – are, interestingly, the scions of earlier ballot measures ripe for resolution. But it’s a surprisingly short list for a state that is used to holding the equivalent of a people’s congress every two years on a broad and diverse policy agenda.

So is our short ballot a sign that state government is functioning well, solving problems and responding to the needs of our people? That’s not meant as a snarky rhetorical question. One could argue that our legislature has been busier than ever, enacting laws to raise the minimum wage, reset business taxes, protect renters, reform policing practices and limit the impact of PERS costs on public services. But the gathering storm of big challenges, from climate change to income inequality and racial injustice, overshadows any checklist of legislative accomplishments and leaves many of us wondering whether the institutions of our representative democracy are up to the task of responding to the crises of the moment.

The good and the bad of a century-long experience with ballot initiatives

"Nyack, NY - 350.org climate change educational table, petition signing and letter writing at Nyack Street Fair. Photo by Laurie Peek" by 350.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The initiative system was born at a time like this, when, a little more than a century ago, the progressive movement confronted the stranglehold of special interests on our legislatures and devised a way to return lawmaking and, just as importantly, political agenda setting to the people. Oregon was a leader in this effort and continued to be a showcase for initiative politics, for better and worse, throughout the 1900s.

Now, I’m well aware of the downsides of the initiative system. I’ve been involved far more often on the No side of ballot measure campaigns than on the Yes side, especially when the process was hijacked by out-of-state, moneyed interests in the 1990s. But I have come to value our initiative process as a way to break through legislative logjams when the heft of public opinion is on your side. Thanks to initiatives, the union movement was able to raise the minimum wage for Oregon workers in 1996 and again in 2002 over the opposition of Republican majorities in the legislature. Then in 2016, it took a well-funded effort by Stand for Children to overcome the resistance of a Democratic legislature on the way to passing an initiative that directed more state funding to career-technical education in our high schools.

I was an advisor to the 2002 and 2016 campaigns, which taught me that needed changes, even when strongly supported by public opinion, are not likely to please whichever party controls the legislature and has other priorities on its agenda.

One can think of the initiative process as a corrective to unresponsive legislatures. Or as a mechanism for advancing deceptively simple policy proposals to a binary Yes/No conclusion. Or as a political tool which, counter to its original purpose, is vulnerable to manipulation by special interests. I concede it is all of the above. But it is also morphing into a means to much healthier political ends.

The initiative process has matured into a more responsible path for citizen engagement

"Voter registration" by Erik R. Bishoff is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In recent years, we’ve seen four ways in which the initiative process has become a more responsible and productive adjunct to our traditional legislative mechanism.

First, the drafting of initiatives has become more sophisticated. Gone are the days when Bill Sizemore would scribble ideas on the back of an envelope and toss them over the transom at the Secretary of State’s office. Practitioners have learned to dot their i’s and cross their t’s when drafting proposals. Just look at this year’s Measure 110.

Second, we’ve learned that access to the initiative process can be just as important as the ability to qualify and win passage of proposals on the ballot. The simple filing of a draft initiative has triggered uh-oh moments for lobbyists, forced opponents to the bargaining table, broken deadlocks on critical issues and ended up moving issues to the fore in the legislature. This is what happened most recently with proposed initiatives to reform Oregon’s forest practices. And we now hear that both major party candidates for Secretary of State would support some form of a redistricting commission as proposed in an initiative that failed to qualify for the 2020 ballot.

Third, the legislature has become more willing to modify measures after their enactment by the voters. We saw this when lawmakers stepped in after the passage of the marijuana initiative in 2014 (Measure 91) and crafted modifications that tailored its provisions to different localities. Rather than raising a hue and cry about protecting the will of the voters, the sponsors of that measure acceded to a process that gave their proposal more credibility and made it more workable.

Fourth, those who design ballot measures that require the use of public funds are now more attentive to how those funds will be spent. Audit and accountability provisions have become standard features of such measures, because the voters, in their skepticism, demand them. We made sure to add these features to Measure 98 (career-technical education) in 2016. And you’ll find similar provisions in Measure 110.

These developments suggest that the use of the initiative in Oregon is maturing. Voters are more wary of simple Yes/No formulations and are more likely to support follow-on legislation that turns Yes into Yes/But and Yes/And answers to our problems. This is a good sign, signaling a way in which the initiative process, with its ability to advance compelling issues, can be reconciled with the legislative process, in which deliberation and compromise come into play. But as any parent can tell you, maturation can be an uneven process.

We’ve made it harder to engage the initiative process when we need more engagement in democratic problem solving

"Meeting on the road" by OregonDOT is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In 2002, I was the author of a successful ballot measure that banned the practice of paying bounties for signatures – a reform which curtailed the incentives for fraud and forgery in the qualification process. I believe it accomplished its purpose. But the enactment of additional safeguards since then, in addition to the bounty ban, have raised the cost of signature gathering and put the initiative process beyond the reach of most grassroots campaigns.

More recently, thanks to legislated limitations on the use of electronic signatures to validate and qualify initiatives for the ballot and now with the pandemic-related constraints on person-to-person contact, access to the initiative process is receding even further from the grasp of citizen activists. Just look at some of the proposed initiatives that were left on the cutting room floor in the current election cycle – from gun control and responses to climate change – that were smart, well-crafted and timely.

This is what gives me pause. We are limiting access to the demand-side power of the initiative process at the same time that…

the challenges we face are overwhelming our electoral institutions,

the legislature is dominated by one party and subject to walkouts by the other, &

we need more cross-partisan citizen engagement to forge consensus on big issues.

All this when a more sophisticated and balanced use of initiatives has been evolving from the good and bad lessons of the last several decades.

It’s time for a redesign of our initiative process

"Canvassing for 'We Are Working America' Week" by AFL-CIO Field is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Oregon pioneered the initiative process to bypass an unresponsive legislature. Now, we should consider revamping that process to strengthen the lawmaking function of a body that is being stymied by partisanship and struggling to make progress on some of the toughest issues to challenge our state. Here are a few ideas to jump start deliberations on what might go into the design of an initiative system 2.0 that can help revitalize our democracy.

1. Lower the signature requirement for proposals that, once approved by the voters, would be submitted to the legislature. Details abound on how to proceed thereafter. Would a floor vote in each chamber be required on either the proposal as submitted or as modified by the legislature? Would the sponsors of proposals that are rejected by the legislature be able to proceed with a ballot-qualifying effort thereafter? However these questions are answered, the goal here is to involve more citizens in identifying compelling problems and in motivating their representatives to forge consensus solutions.

2. Raise the signature threshold for constitutional amendments. Often, sponsors of initiatives will opt for framing them as constitutional amendments for the sole purpose of insulating them from legislative modifications. Our constitution is cluttered with the detritus of these tactics. But, more importantly, using the constitution as a bullet proofing shield for policy measures preempts the better process of getting to Yes/But and Yes/And through deliberation and compromise. The processes of government belong in our constitution, and a refashioned initiative process can only be accomplished by constitutional amendment. But policy measures, including those related to taxation, don’t belong in the constitution and should be subject to legislative changes in changing times.

3. Modernize the signature gathering process to allow for electronic signatures through the Secretary of State’s website. Signature gathering is a means to the end of establishing a threshold of voter interest for particular proposals. It is also a way of engaging citizens in the debates that should drive our democracy. With more of our daily transactions moving online, our processes for citizen input should follow.

I suspect there will be instinctive opposition to these ideas from colleagues with whom I worked on those many “Just Vote No” campaigns in the past. There is a strong case to be made that democracy works best when it operates through the deliberations of well-organized representative assemblies rather than by attempting to harmonize a cacophony of citizen demands framed as Yes/No propositions. But this is not an either/or matter. With smart reforms, we can combine the energy of engaging our people in agenda setting with the benefit of an elected legislature empowered by voter demands to get things done.

Think of the question I posed earlier – about whether state government is functioning well, solving problems and responding to the needs of our people. Most Oregonians don’t think so. Our democracy needs help. And it just may be that our old initiative process, when updated to reflect the experiences of one century and the methods and needs of another, can provide a foundation for revitalizing citizen engagement and consensus building, as we search for new ways to meet the challenges of our time.

***********************

Keep the conversation going via our Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/oregonway) or Twitter (@the_oregon_way)