When Redistricting, First Isn't Always Best: Oregon Has Room for Improvement

Oregon was the first state to redraw Congressional districts, but it wasn’t pretty.

As headlines from OPB to CNN have documented, Gov. Kate Brown signed the State Legislature’s redistricting legislation, mere hours before an Oregon Supreme Court deadline. The new maps establish Oregon’s congressional districts for the next decade—including the new sixth district.

The legislative deal ended a contentious redistricting process marked by escalating distrust between party leaders. On Sep. 20, Speaker Tina Kotek pulled out of an April deal she had made with Republicans. According to that agreement, Republicans would allow normal legislation to move through the legislative process and cease to use tactics like requiring every bill to be read aloud on the House floor, which effectively halted the legislative process. In exchange, Democrats would give Republicans an equal number of seats on the House Redistricting Committee.

In her Sep. 20 announcement, Speaker Kotek changed course and indicated she would create two committees for the redistricting process, one committee for the national maps that would have two Democrats and one Republican, and another committee for the state legislative maps that would be evenly balanced. In doing so she scrapped the original committee that would draw both maps and include an even split of Democrats and Republicans.

When Kotek pulled back from the deal, she justified it by saying that Republicans were not meeting her expectations of what good faith negotiations should look like. In response, most House Republicans left the Capitol, preventing the process from moving forward.

House Republicans found themselves in a bind. They could have prevented Democrats from passing their preferred maps by not showing up. However, if no deal was reached the opportunity to draw the lines would shift to Secretary of State Shemia Fagan, an outcome Republicans reportedly thought could be more disadvantageous than the maps passed in the Legislature.

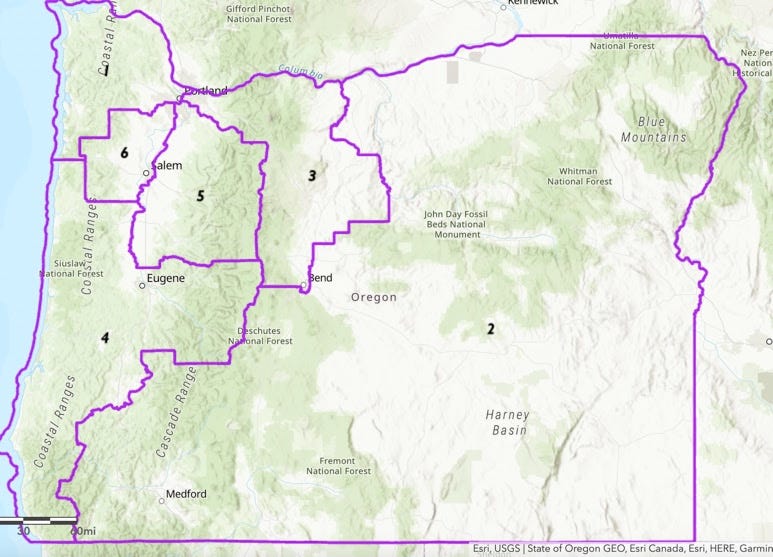

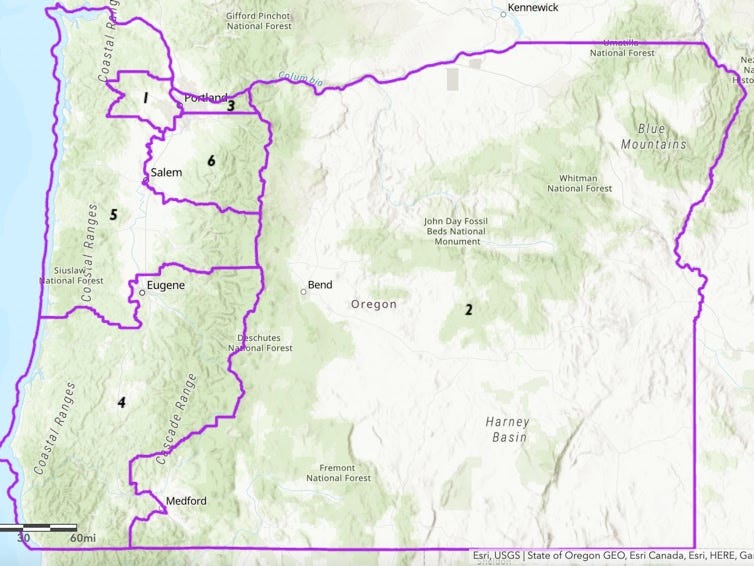

Fearing this, sixteen Republicans returned on Monday and allowed the map created under the new process to pass (despite voting against it), which will, legal challenges excepting, shape Oregon’s congressional elections and delegation for the next decade:

Compare the map passed by the legislature and signed by Gov. Brown with the two initial proposals presented by House Democrats and Republicans respectively:

MAP A

MAP B

Map A was preferred by Democrats and Map B by Republicans. As Peter Sage wrote in the Oregon Way last month and a PlanScore analysis confirms, Map A would favor Democrats for five of Oregon’s six seats and Map B would put Republicans in a strong position in four of the six districts.

If either of these maps were adopted, it would set a path for Oregon’s congressional delegation to be far out of step with Oregon’s voting pattern as a state. In the last five presidential elections, the Democratic candidate has won 56% in 2020, 50% in 2016, 54% in 2012, 57% in 2008, and 51% in 2004, and a similar pattern holds in midterm elections.

Map A would give Democrats a decent chance at holding 83% of the congressional seats, while Map B would give Republicans at landing 66% of seats if they won two toss-up districts. For context, if the the Supreme Court had adopted the standards anti-gerrymandering advocates suggested in the 2018 case Gil v. Whitford, both proposals would likely have been declared unconstitutional. For more context and analysis of these maps check out 538 and PlanScore.

The map finally adopted by the Legislature is much closer to Plan A, but contains some important changes. Map A would have created two safe Democratic seats in Portland, a safe Republican seat in eastern Oregon, and three seats that leaned Democratic by four to six points. Meanwhile, the adopted plan creates a highly competitive 5th district, without making either of the six point districts any easier for Democrats.

However, it should be noted that the cracking of Portland into multiple districts is the main reason Democrats are able to draw a map that results in them winning in five out of six of the seats. The current congressional map and the Republican proposal have three districts running through Portland, while the initial Democratic proposal and the one passed Monday split the Portland area into fourths, like a pinwheel. Splitting Portland into fourths allows Democrats to be far more competitive in the central Oregon and coastal districts.

Although most Republicans returned to pass new maps before the deadline, Minority Leader Christine Drazan, R-Canby, immediately attempted to censure Speaker Kotek. The motion failed 33-14, but showed how this process is a symptom and cause of ongoing procedural dysfunction.

Almost former political science student with too many polemical thoughts for his own tired brain.