Solving the Literacy Crisis in Oregon

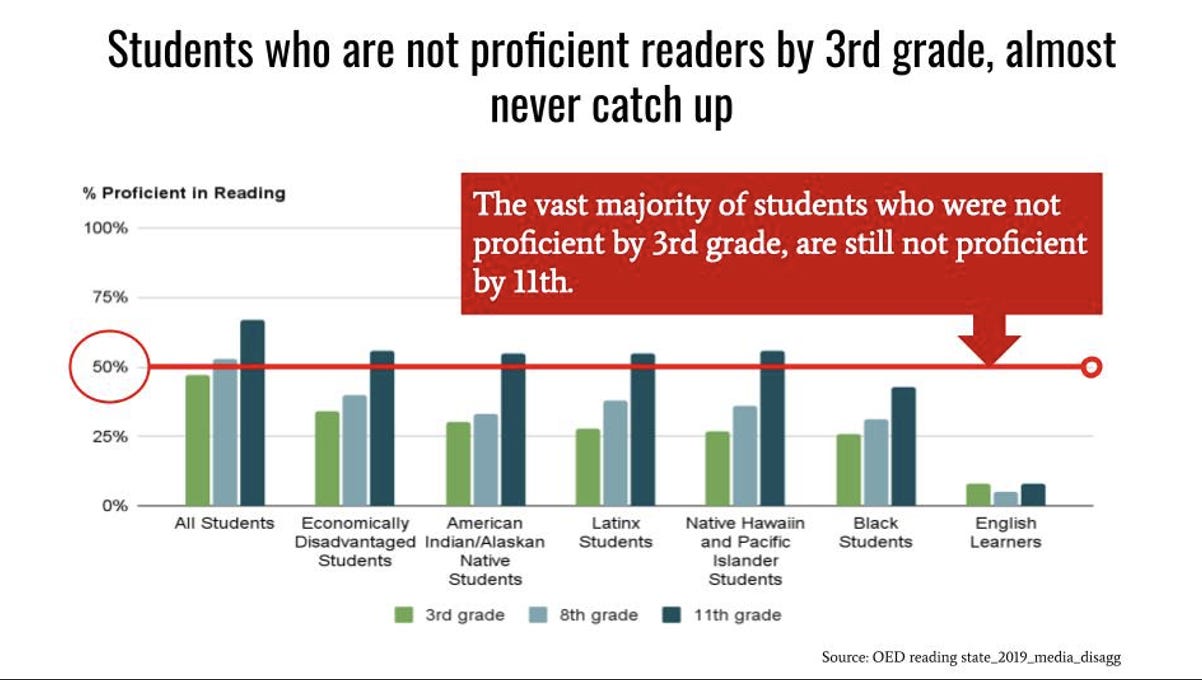

Oregon has a literacy crisis. In 2019, only 46.5% of students were proficient in reading by 3rd grade—and that was before COVID-19.

Can you imagine not being able to read this article? How about a menu? A job application? A medical pamphlet about your child’s asthma?

For those of us who can read, illiteracy is unimaginable. Reading has become invisible to us because we can’t remember a time when we couldn’t read. And what we can’t imagine, we can’t fix.

Oregon has a literacy crisis. In 2019, only 46.5% of students were proficient in reading by 3rd grade—and that was before COVID-19.

Why Third Grade Reading Matters

By the end of 3rd grade, children shift from learning to read to reading to learn. In math, they start working on word problems. In social studies, they’re looking at primary sources. In science, they’re reading about how the universe works.

Now imagine you’re a struggling reader. You’re confused. Frustrated. Does your teacher think you’re just lazy? Will your friends make fun of you? How long before you stop trying? Go quiet? Act out? Stop showing up?

Of students who do not meet third grade reading benchmarks, 16% do not graduate from high school, a rate four times greater than for proficient readers. US adults who don’t finish high school have the highest unemployment rates and lowest median earnings. Of children involved with the juvenile justice system, 85% are struggling readers. 70% of inmates in America’s prisons cannot read above a fourth-grade level. Two-thirds of students who cannot read proficiently by the end of fourth grade will end up in prison or on government assistance.

Reading Is a Skill That Can Be Taught

Critics of increased school-based interventions argue that the problem isn’t about reading but rather about kids’ home lives. Forty years of research shows this is simply not true. The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) states, “While parents, tutors, and the community can contribute to reading success, classroom instruction must be viewed as the critical factor in preventing reading problems and must be the primary focus for change.” The role of teachers is even more important for students, such as English language learners, who are dependent on school-based experiences to develop reading skills.

In 2009, Oregon’s Literacy Framework stated, “The basic fact is that too many students are graduating from Oregon high schools without the key reading skills necessary for postsecondary education and career opportunities. The paradox is that many [of these students] were actually experiencing difficulties learning to read as early as kindergarten. These students could have been easily identified at that time, and if scientifically-based instructional interventions had been used, the chances are good that many of them would have acquired the reading skills they needed for a lifetime of learning.”

Almost all children can learn to read if they are taught in an explicit and systematic way, what is often called the science of reading or structured literacy. So why has Oregon’s literacy crisis only worsened since 2009? It is because most teachers lack training in the science of reading.

What we can do

First, teachers and administrators must be trained in the science of reading. In the past 18 months, Portland Public Schools has provided professional development to over 450 educators using a scalable and cost-effective program. All districts need the support and funds to provide their teachers with this essential training.

Second, we must change how our teachers are trained in their Educator Preparation Programs (EPPs). Only 53% of EPPs properly prepare future teachers to teach all children to read. In a national ranking of EPPs, Oregon ranked last (51/51) in terms of how many EPPs in the state adequately addressed evidence-based reading instruction. When pre-service teachers do not receive this training, school districts must spend millions to retrain them.

Third, Oregon’s Teacher Standards and Practices Commission must require all teacher candidates to pass a Foundations of Reading Test, a rigorous examination of evidence-based reading instruction and data-based decision-making principles.

Oregon will never achieve educational equity without these changes. When teachers are not adequately trained, students of color, English learners, and low-income students suffer the worst consequences. Well-resourced students do better not because their teachers have more training but because their families can spend thousands on private tutors trained in the science of reading.

A comprehensive state-wide literacy strategy should also address other issues, such as curricula, literacy coaches, and screening. However, these efforts will not turn the page on Oregon’s literacy crisis until we first change how reading is being taught to all students by all teachers.

Change is difficult, but it’s also possible. It starts with training Oregon’s teachers in the most effective ways to teach kids to read.

Jennifer is a literacy advocate with Oregon Kids Read and has worked in finance, academics, and nonprofits. She also writes novels and draws one-panel cartoons.

Photo credit: "The Kids Reading Ramona Books In Honor Of Beverly Cleary's 100th Birthday" by Joe Shlabotnik is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Former special education teacher speaking here. No one program adequately addresses literacy, because most focus on one aspect or another of the three elements which make up literacy to the exclusion of the others (decoding, comprehension, and fluency). I have worked with students who have two of the three pieces but lack a third. Just because a student can decode fluently does not mean they possess comprehension.

What is needed is a.) early identification of reading strengths and weaknesses and b.) targeted programs which address specific elements of reading disability. Too many programs focus on phonetic awareness but not on meaning.