What Nick Kristof's writing tells us about his potential campaign for Oregon Governor

We explore Kristof's brand as a Democrat, likely campaign priorities, friction points with the base, fundraising capacity, and potential controversies.

The last time a journalist became governor of Oregon, then-Secretary of State Tom McCall (R-Portland) had just bested then-Treasurer Bob Straub (D-Lane County) in 1966. In a passage from Fire at Eden’s Gate (one of the best books about Oregon that’s ever been written), author Brent Walth describes McCall telling Tom Dargan, his boss at KGW, “Damn it, I could be governor if you let me.” He meant that he needed the money that his TV job provided, but he knew he couldn’t keep the gig if he ran for office. Dargan — who believed in McCall — agreed to assign him an off-camera job while he campaigned. The rest is history.

Fast forward to today, and Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times columnist Nick Kristof’s secret is out: he’s thinking about following in McCall’s footsteps and running for Governor (in fact, he twice invoked McCall in his June interview with KGW…perhaps in a subtle effort to encourage us to see some similarities).

Kristof, however, has already announced he will leave The Times if he runs. One has to wonder: is Kristof willing to give up what must be one of the best jobs in the world for a chance to be Oregon governor? Or perhaps New York Times Editor-in-Chief Dean Baquet, like Tom Dargan in 1964, will offer Kristof the security of coming back if things don’t work out. But maybe, after 37 years at The Times, Kristof is ready for a new adventure, regardless of how the campaign goes.

Time will tell. Until then, let’s explore what a potential Nick Kristof for Governor campaign might look like.

What kind of Democrat is Nick Kristof?

In short: he’s an economic populist likely to focus on working-class, social inequality, and anti-poverty issues.

In an April column called “Lessons for America From a Weird Portland,” Kristof defends the city of Portland (while criticizing its leaders) and, more interestingly, identifies two “wings” in the Democratic Party:

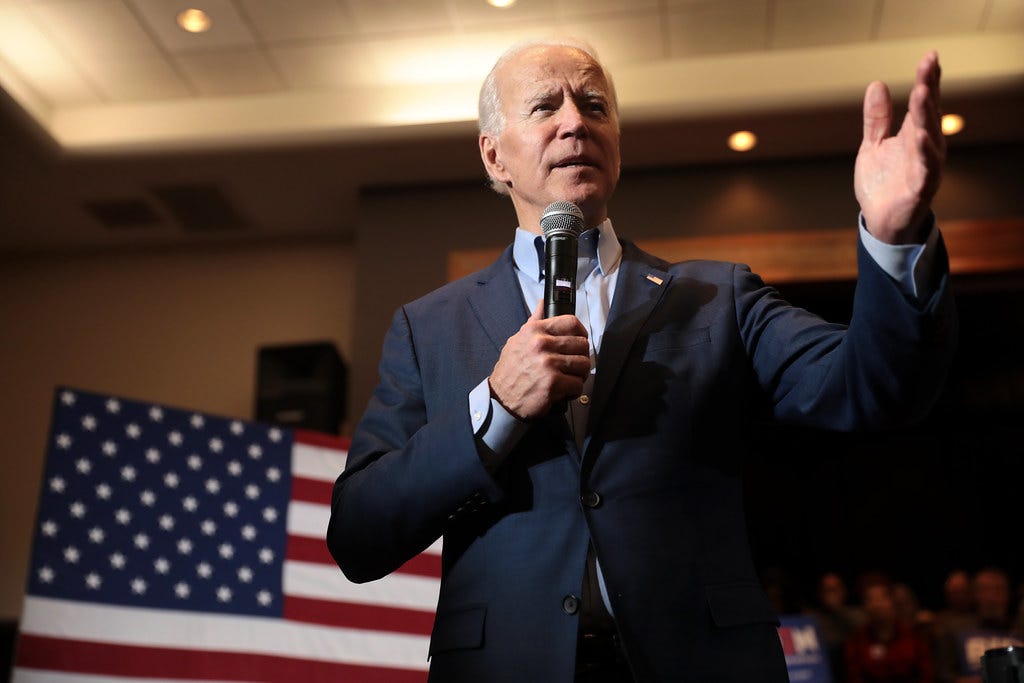

“One wing of the Democratic Party, encompassing President Biden but also policy wonks to his left like Elizabeth Warren, focuses on practical steps to improve people’s lives: vaccinations, broadband, highways, child allowances, daycare. Another wing of the party emphasizes identity politics and theatrical grand gestures to redress historical wrongs and push for a fairer society.”

If it wasn’t clear to which wing Kristof belongs, here’s the last line of the column.

“…bravo for Biden and others focusing on tangible, nitty-gritty — sometimes revolutionary — improvements in real people’s lives. Grand gestures for justice are fine, but they can’t substitute for quiet competence in keeping people safe, getting people housed or picking up the garbage.”

What might Kristof’s campaign platform look like?

First, if Kristof runs, expect a policy-forward campaign. He writes about policy ideas frequently, and he lavished praise on Senator Elizabeth Warren for the type of policy-driven campaign she ran. While most of his writing focuses on international and national issues, there are some clues about how those issues might translate in Oregon.

Kristof wrote a piece in February called “Can Biden Save Americans Like My Old Pal Mike?” It’s a beautiful and painful piece about a troubled childhood friend of Kristof’s who, simply put, couldn’t make it in American society (put another way: he was failed by American society). In the column, he lists “five policies to create opportunity” (remember, he is speaking in the national context). If he runs, expect an “Oregon version” of these policies:

High-quality early childhood education and daycare programs

A higher minimum wage and more job training

A “huge expansion of drug treatment programs”

A child allowance (for which he tips his hat to President Joe Biden)

An expansion of high-speed internet, particularly in rural areas

Another policy he may pursue? Housing vouchers. Literally paying people to move to more economically and educationally prosperous places. It’s been done in Seattle and has been advocated for by Harvard economist Raj Chetty (learn more about this idea and others here: Opportunity Insights).

And, some red meat for the base: Kristof is sure to advocate taking on the NRA and passing more gun safety measures.

Kristof also has a track record of writing about racial justice issues in the U.S., especially following the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson. Mostly, he has called for more “uncomfortable conversations”, particularly among white people, and “soul searching” on racial issues, while describing, with both statistics and stories, what racism looks like in America.

Kristof has been a champion for abortion and contraceptive access (internationally and nationally), so he will certainly run as a pro-choice advocate.

Where might Kristof encounter friction in the Democratic primary?

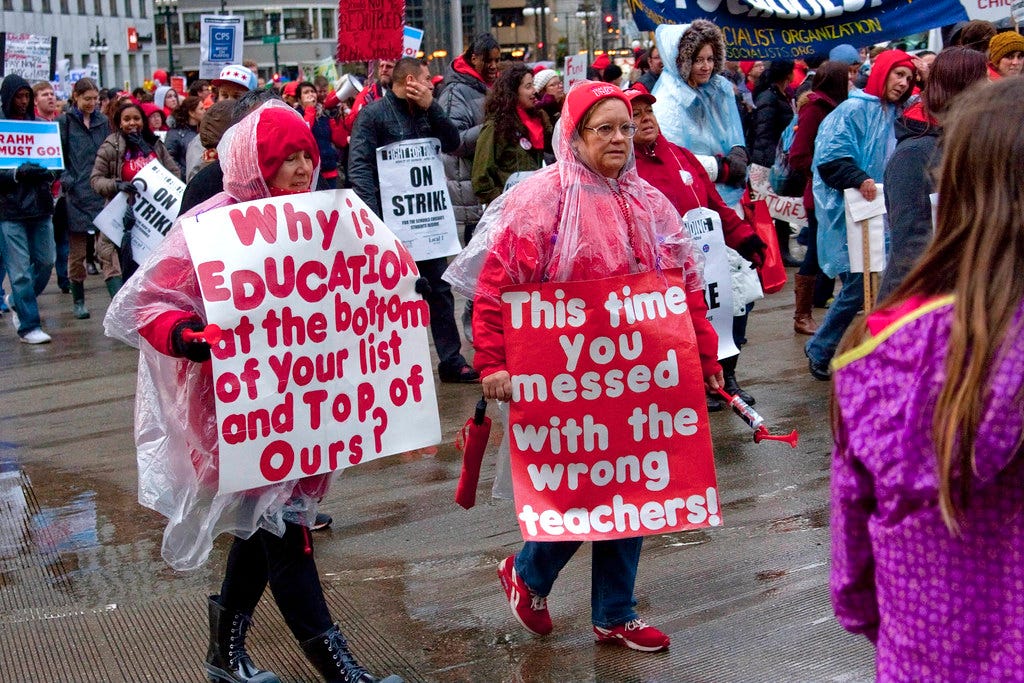

Two major areas: teachers’ unions and sweatshops.

TEACHERS’ UNIONS: In Oregon, the Oregon Education Association (OEA), the largest teachers’ union in the state, is a powerful political force. The group endorses and donates large sums of money to candidates — and they’re part of the larger progressive movement (a movement that seems to be increasingly coordinated in Oregon) that includes fellow public-sector labor unions, pro-choice groups, and environmental organizations.

It is here that Kristof will have a problem. He has been a vocal critic of teachers unions for years. From a 2011 column: “I’m not a fan of teachers’ unions. They used their clout to gain job security more than pay, thus making the field safe for low achievers.”

Kristof has acknowledged the power of teachers unions on the left, once writing that the Democrats were “cowed by teachers’ unions.” Democrats, he said, “too often resisted reform and stood by as generations of disadvantaged children have been cemented into an underclass by third-rate schools.” Ouch.

Eight years ago, he also acknowledged that he may be outside the mainstream of his left-wing audience on this issue: “I have lots of folks who like my work on so many subjects but think I'm brain-dead on education.”

Here are the specific education policies that he has favored to fix our “faltering education system” (his words in 2012; in 2015 he called education “our greatest national shame”) that are generally unpopular with teachers’ unions:

Merit pay for teachers (paying “good” teachers more than “average” or “bad” teachers) and firing under-performing teachers

Teacher evaluations based on student performance (i.e. using standardized test scores to determine, at least partly, which teachers are effective)

And a newer issue: keeping schools open during the pandemic

Takeaway: In 2015, Kristof seemed to acknowledge the intractability of these issues, calling for a détente in the education reform wars and a collective focus on early childhood education issues (kids age 0-5).

SWEATSHOPS: He once wrote that sweatshops are “an unpleasant but necessary stage in industrial development.”

In an “Ask Me Anything” on Reddit, Kristof explained his rationale: “I think the critics of sweatshops are right in their criticisms, and on top of those problems some of those factories also have environmental issues (e.g. dump pollution in a river). But the big need in poor countries is jobs, jobs, jobs.” According to Kristof, many of those jobs benefit women in particular.

As mentioned above, labor unions are very powerful allies in a Democratic primary campaign. In 2015, Kristof became a vocal proponent of unions (after previously being more critical). Unions won’t agree with Kristof on sweatshops. And while this is an issue with little relevance in a Governor’s race, in a crowded field of labor-friendly Democrats, it will make for a convenient talking point for his opponents.

One potential Kristof response to skeptical unions: “At least I didn’t cut your pensions.”

What are the other Kristof controversies?

The internet is full of pieces critical of Nick Kristof, from both the right and the left. That’s what happens when you write thousands of columns over three decades in one of the most widely-read newspapers in the world. We don’t expect these issues to matter much in a gubernatorial election, but they help paint a fuller picture of Kristof and how he thinks:

SAVIOR COMPLEX?: In a scathing critique titled “The White Knight” published in Slate, Amanda Hess explores several examples of Kristof being duped by subjects of his articles (mostly pieces focused on international poverty and human rights), and his tendency to promote American protagonists over the work of locals in his column.

Kristof offered a clear-eyed response to the Hess article to Politico.

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION?: In 2004, as the public opinion was quickly shifting toward disapproval of the Iraq War, Kristof wrote a piece that defended President George W. Bush from accusations that he was a liar. Some on the anti-war left (many of whom still believe that Bush intentionally lied as a pretense for war) were not happy. To be clear, Kristof was still critical of Bush: “Mr. Bush's central problem is not that he was lying about Iraq, but that he was overzealous and self-deluded.”

In the piece, Kristof seemed to imagine today’s political polarization, which we saw rapidly accelerate beginning in 2010 with the Tea Party: “I'm against the ‘liar’ label for two reasons. First, it further polarizes the political cesspool, and this polarization is making America increasingly difficult to govern. Second, insults and rage impede understanding.”

CHAIRMAN MAO: Kristof wrote a book review in 2005 where he wrote: “I agree that Mao was a catastrophic ruler in many, many respects, and this book captures that side better than anything ever written. But Mao's legacy is not all bad.” He cites land reform, the emancipation of women, and the end of child marriages. Earlier in the piece, he refers to Mao as a monster. People were still pissed.

James Panero, in a response column in The New Criterion, writes: “Kristof’s disgraceful conclusion to his review speaks volumes to the acceptability and even expectability in intellectual circles of praising the most murderous villain—in terms of numbers killed—of the twentieth century.” He goes on to call the column a “shameful display” and a “critical and moral breakdown.”

ON BEING WRONG: Back in 2012, Kristof acknowledged some (very dated 2000s-era) things he has been wrong about: the surge in Iraq, sanctions in Burma, and investigating a government doctor related to anthrax.

Can Kristof raise enough money to be competitive in Oregon’s “Wild West” campaign finance system?

The answer is almost certainly yes. It seems unlikely, given his newcomer status without a voting record to stand on in a crowded field, that he’ll be able to win over traditional progressive powerhouse organizations (labor, environmentalists, pro-choice groups, etc.). They are likely to stick with known quantities that they trust. If that’s true, then millions of potential institutional dollars are off the table for Kristof.

But—he might not need those dollars (and they’ll be there in the general election if he wins the primary). It doesn’t take much sleuthing to figure out that Kristof has friends in powerful places. His work has been praised by many influential (and wealthy) individuals, including former President Bill Clinton, actor Ben Affleck, and Bill and Melinda Gates. It’s hard to imagine his cell phone address book not including several multi-millionaires. Without contribution limits, a handful of well-financed boosters could vault Kristof to the front of the fundraising pack. Any downside (e.g. the optics of big checks from out of state) would surely be outweighed by the benefits of a big bank account—plus, the other candidates will have some big, out-of-state dollars, too.

But, in order to get money, you have to ask for it. Fundraising is essentially unanimously agreed upon as the absolute worst part of campaigning. Willamette Week editor Mark Zusman wonders: is Kristof “the type of guy who will dial for dollars?” If he wants to win, he will likely need north of a million dollars (the actual number will depend on dynamic primary factors). One former legislative candidate told me he thinks some candidates will raise over $7 million for the primary alone. That would be as much as John Kitzhaber raised in his entire campaign in 2010, and almost $3 million more than he raised in 2014. Mind-boggling!

His greatest fundraising advantage: most liberal donors would love to take a phone call from Nick Kristof.

Don’t forget: Kristof is a bestselling author, and his wife and co-author, Sheryl WuDunn, works in finance. Plus, he’s got over 2 million Twitter followers!

Author’s Note: Nick, if you do end up leaving The New York Times, please tell Dean Baquet that I’m available to fill the “liberal columnist from Oregon” slot.

I realize as a minority Oregonian who does not subscribe to Portlands politics that nothing outside of the metro area counts in a statewide election but can you imagine how a liberal new york times employee will be viewed.